The Economist: What companies are for

Competition, not corporatism, is the answer to capitalism’s problems

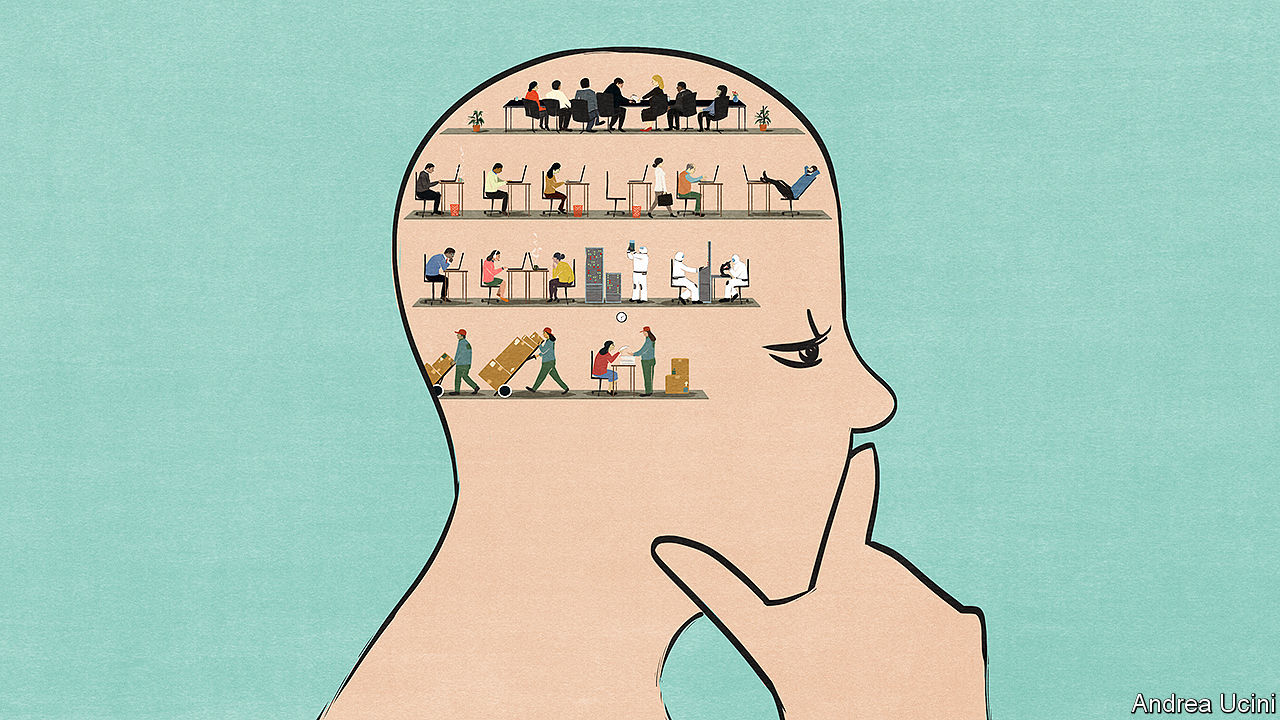

ACROSS THE West, capitalism is not working as well as it should. Jobs are plentiful, but growth is sluggish, inequality is too high and the environment is suffering. You might hope that governments would enact reforms to deal with this, but politics in many places is gridlocked or unstable. Who, then, is going to ride to the rescue? A growing number of people think the answer is to call on big business to help fix economic and social problems. Even America’s famously ruthless bosses agree. This week more than 180 of them, including the chiefs of Walmart and JPMorgan Chase, overturned three decades of orthodoxy to pledge that their firms’ purpose was no longer to serve their owners alone, but customers, staff, suppliers and communities, too.

The CEOs’ motives are partly tactical. They hope to pre-empt attacks on big business from the left of the Democratic Party. But the shift is also part of an upheaval in attitudes towards business happening on both sides of the Atlantic. Younger staff want to work for firms that take a stand on the moral and political questions of the day. Politicians of various hues want firms to bring jobs and investment home.

However well-meaning, this new form of collective capitalism will end up doing more harm than good. It risks entrenching a class of unaccountable CEOs who lack legitimacy. And it is a threat to long-term prosperity, which is the basic condition for capitalism to succeed.

Ever since businesses were granted limited liability in Britain and France in the 19th century, there have been arguments about what society can expect in return. In the 1950s and 1960s America and Europe experimented with managerial capitalism, in which giant firms worked with the government and unions and offered workers job security and perks. But after the stagnation of the 1970s shareholder value took hold, as firms sought to maximise the wealth of their owners and, in theory, thereby maximised efficiency. Unions declined, and shareholder value conquered America, then Europe and Japan, where it is still gaining ground. Judged by profits, it has triumphed: in America they have risen from 5% of GDP in 1989 to 8% now.

It is this framework that is under assault. Part of the attack is about a perceived decline in business ethics, from bankers demanding bonuses and bail-outs both at the same time, to the sale of billions of opioid pills to addicts. But the main complaint is that shareholder value produces bad economic outcomes. Publicly listed firms are accused of a list of sins, from obsessing about short-term earnings to neglecting investment, exploiting staff, depressing wages and failing to pay for the catastrophic externalities they create, in particular pollution.

Not all these criticisms are accurate. Investment in America is in line with historical levels relative to GDP, and higher than in the 1960s. The time-horizon of America’s stockmarket is as long as it has ever been, judged by the share of its value derived from long-term profits. Jam-tomorrow firms like Amazon and Netflix are all the rage. But some of the criticism rings true. Workers’ share of the value firms create has indeed fallen. Consumers often get a lousy deal and social mobility has sunk.

Regardless, the popular and intellectual backlash against shareholder value is already altering corporate decision-making. Bosses are endorsing social causes that are popular with customers and staff. Firms are deploying capital for reasons other than efficiency: Microsoft is financing $500m of new housing in Seattle. President Donald Trump boasts of jawboning bosses on where to build factories. Some politicians hope to go further. Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic contender for the White House, wants firms to be federally chartered so that, if they abuse the interests of staff, customers or communities, their licences can be revoked. All this portends a system in which big business sets and pursues broad social goals, not its narrow self-interest.

That sounds nice, but collective capitalism suffers from two pitfalls: a lack of accountability and a lack of dynamism. Consider accountability first. It is not clear how CEOs should know what “society” wants from their companies. The chances are that politicians, campaigning groups and the CEOs themselves will decide—and that ordinary people will not have a voice. Over the past 20 years industry and finance have become dominated by large firms, so a small number of unrepresentative business leaders will end up with immense power to set goals for society that range far beyond the immediate interests of their company.

The second problem is dynamism. Collective capitalism leans away from change. In a dynamic system firms have to forsake at least some stakeholders: a number need to shrink in order to reallocate capital and workers from obsolete industries to new ones. If, say, climate change is to be tackled, oil firms will face huge job cuts. Fans of the corporate giants of the managerial era in the 1960s often forget that AT&T ripped off consumers and that General Motors made out-of-date, unsafe cars. Both firms embodied social values that, even at the time, were uptight. They were sheltered partly because they performed broader social goals, whether jobs-for-life, world-class science or supporting the fabric of Detroit.

The way to make capitalism work better for all is not to limit accountability and dynamism, but to enhance them both. This requires that the purpose of companies should be set by their owners, not executives or campaigners. Some may obsess about short-term targets and quarterly results but that is usually because they are badly run. Some may select charitable objectives, and good luck to them. But most owners and firms will opt to maximise long-term value, as that is good business.

It also requires firms to adapt to society’s changing preferences. If consumers want fair-trade coffee, they should get it. If university graduates shun unethical companies, employers will have to shape up. A good way of making firms more responsive and accountable would be to broaden ownership. The proportion of American households with exposure to the stockmarket (directly or through funds) is only 50%, and holdings are heavily skewed towards the rich. The tax system ought to encourage more share ownership. The ultimate beneficiaries of pension schemes and investment funds should be able to vote in company elections; this power ought not to be outsourced to a few barons in the asset-management industry.

Accountability works only if there is competition. This lowers prices, boosts productivity and ensures that firms cannot long sustain abnormally high profits. Moreover it encourages companies to anticipate the changing preferences of customers, workers and regulators—for fear that a rival will get there first.

Unfortunately, since the 1990s, consolidation has left two-thirds of industries in America more concentrated. The digital economy, meanwhile, seems to tend towards monopoly. Were profits at historically normal levels, and private-sector workers to get the benefit, wages would be 6% higher. If you cast your eye down the list of the 180 American signatories this week, many are in industries that are oligopolies, including credit cards, cable TV, drug retailing and airlines, which overcharge consumers and have abysmal reputations for customer service. Unsurprisingly, none is keen on lowering barriers to entry.

Of course a healthy, competitive economy requires an effective government—to enforce antitrust rules, to stamp out today’s excessive lobbying and cronyism, to tackle climate change. That well-functioning polity does not exist today, but empowering the bosses of big businesses to act as an expedient substitute is not the answer. The Western world needs innovation, widely spread ownership and diverse firms that adapt fast to society’s needs. That is the really enlightened kind of capitalism.■

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition under the headline “What companies are for”