Star Tribune: Farm bankruptcies are on the rise, and bankers worry that far more are on the way

Star Tribune photos

The increase in Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings reflects low prices for corn, soybeans, milk and even beef.

by Adam Belz, Star Tribune | November 26, 2018

Farm bankruptcies are rising in the Midwest and bankers worry more are on the way.

Farm bankruptcies are on the rise in Minnesota and across the Upper Midwest.

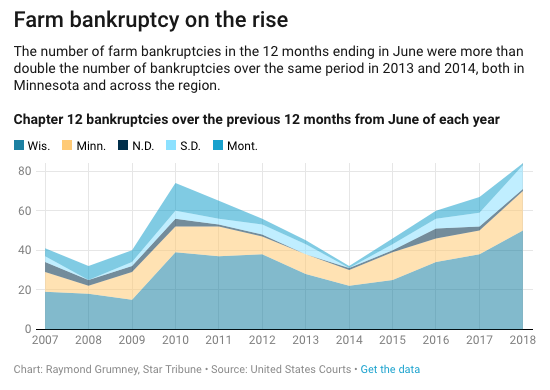

Eighty-four farms filed for Chapter 12 bankruptcy in Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana in the 12 months that ended in June, according to a new analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. That’s more than double the number over the same period in 2013 and 2014, and the number of bankruptcies in Minnesota doubled over the past four years from eight to 20.

Banks are also seeing more farm borrowers fall behind on their payments, and the worst is likely yet to come.

“Current price levels and the trajectory of the current trends suggest that this trend has not yet seen a peak,” Ron Wirtz, an analyst at the Minneapolis Fed, wrote.

The increase in Chapter 12 filings reflects low prices for corn, soybeans, milk and even beef. The situation for most farmers has worsened since June under retaliatory tariffs that have closed the Chinese market for soybeans and damaged exports of milk and pork.

Farmers use Chapter 12 bankruptcy because it combines the simplicity of Chapter 13 bankruptcy — usually used by individuals — and the higher debt levels allowed with Chapter 11 bankruptcy — usually used by corporations. The Chapter 12 process typically allows for repayment of debt over three years.

Mark Miedtke, the president of Citizens State Bank in Hayfield, Minn., said bankruptcy hasn’t reared its head for borrowers in his area of southeast Minnesota, but farmers are struggling.

“Dairy farmers are having the most problems right now,” Miedtke said. “Grain farmers have had low prices for the past three years but high yields have helped them through. We’re just waiting for a turnaround. We’re waiting for the tariff problem to go away.”

The underlying problem, which existed before the trade war, was overproduction. Farmers are almost too efficient for their own financial good, Miedtke said, and demand hasn’t kept pace with the abundant American supply of corn and soybeans.

While lower land prices will lower rents and affect the cost of farming, the spring, when farmers must secure new lines of credit, will be a telling time.

“The picture could start changing this spring,” Miedtke said. “We do what we can to try to work with farmers.”

The problem is showing up in other parts of the Midwest, too. A new report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, which covers Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming and portions of Missouri and New Mexico, showed that more than half of bankers in the district reported lower farm income than a year ago. They also said they expect farm income to weaken in coming months.

The worst ag banking conditions were in states with the heaviest concentrations of corn and soybeans. Almost all bankers in those states reported that farmers plan to sell land or equipment to try to make loan payments.

In the Minneapolis Fed’s Ninth District, Wisconsin was responsible for 60 percent of all bankruptcies last year.

Bankruptcy is not the only measure of stress in the farm economy. The dairy industry, especially, is struggling, and many dairy farmers are skipping bankruptcy and leaving the business altogether.

The number of licensed dairies in Wisconsin, for example, has fallen by about 1,200 — or 13 percent — from 2016 through October of this year, according to federal and state data.