Rural America Doesn’t Have to Starve to Death

Rural America Doesn’t Have to Starve to Death

A predatory and extractive financial sector has hollowed out communities across the US.

February 18, 2020

Losing ground: US farm output has more than doubled since the 1850s, but farmers like Ray Martinmaas in Orient, South Dakota, aren’t benefiting. (Ricky Carioti / The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Last June, The Washington Post published an article featuring Ray Martinmaas, a farmer in Orient, South Dakota. He said family farmers were losing out in the trade fight with China and weren’t benefiting enough from $14.5 billion in recently promised direct federal aid. He and his wife, Becky Martinmaas, the article read, “share a commitment to hard work and family, a love of sport shooting and hunting, and a distaste for coastal elites.” He voted for Donald Trump but now wasn’t so sure. “We’re the ones taking the brunt of it in all these negotiations,” he said, “so they need to be kind of helping us out.”1

In the comments, Ray Martinmaas got hammered. Many were furious he voted for Trump, but others said farmers were welfare queens who “disdain the coastal elites who pay their bills,” as one put it. “The sheer ignorance of thinking they feed us. When it’s us feeding them.” Another anonymous commenter put it more darkly, writing, “The flyover Red States farmers and ranchers [must] pay for their self-centered decades of whining and begging.”2

Such remarks reflect two popular narratives about agriculture. The first is that the (not always coastal) big money centers like New York and Chicago and the billionaires who work there are the real wealth creators, showering jobs and handouts on grasping Midwestern farmers. The second holds that the decline of many small farming communities is a result of the inevitable march of progress—tractors and machines replacing farm labor and other long-term trends. To save dying rural communities, this story goes, we’d need to return to a bucolic past of pitchforks and plow horses. “What we see, obviously, is economies of scale having happened in America,” Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said approvingly last October. “Big get bigger, and small go out.”3

Yet both the narrative that subsidies flow from “coastal elites” to farmers and the fatalism about rural economic decline indicate a profound misunderstanding of what’s actually going on. Farmers have as much reason to be angry, if not more, because of the larger, less visible financial flows heading in the other direction, sucked out of their pockets and funneled to the big money centers, often into offshore tax havens. This is part of a broader phenomenon affecting the entire economy, which I call the finance curse. The good news is that this can be decisively reversed without turning the clock back on progress—and with transformative economic and political results.

While traveling in Iowa in late 2018, I saw on television the science-fiction classic Back to the Future, in which the hero, Marty McFly, is transported to the town of Hill Valley in 1955. The film features a thriving town square with bustling shops, theaters, shiny convertibles, and testosterone-fueled teenagers—an idealized image that nevertheless reflects the real prosperity and genuine community spirit found in many rural American communities in those days.

But something funny has since happened, a kind of paradox. Mechanization, clever genetic manipulation, information technology, and advanced management practices have multiplied the wealth creation from American farmland. The total output of the US farming sector is now roughly two and a half times what it was in Marty McFly’s era. Yet large parts of rural America have been hollowed out. Suicide rates among farmers are high. According to the American Farm Bureau Federation, median on-farm income (as opposed to off-farm income, from working other jobs) has averaged a negative $1,569 per year from 1996 to 2017. More than half of farm households now lose money from farming. They keep going only because family members work other jobs.

There’s the paradox: Despite more farming wealth than ever, farming communities are poorer. Why?

This past November, I was shown around Williams in central Iowa, a pretty, tree-filled four by 12 lattice of streets, with painted wooden houses set in neatly cut lawns and three churches—one Lutheran, one Catholic, one Methodist—serving around 350 residents. Nick Schutt (pronounced shoot), a beefy, bearded corn and soybean farmer, took me down the road from his childhood home to the local meat locker, which closed two years earlier. The antiques and crafts store was also recently shuttered. The tavern, where he played pool, closed a few years ago. Williams once had three grocery stores, three dealers in farm implements, and four gas stations, two on the highway and two in town, all competing for business. There was a creamery, a chicken hatchery, a doctor’s office, a stockyard, and a buying station for livestock from the surrounding area—all gone. His father, Tom Schutt, reminisced: “They’d have a band in summertime, every Wednesday night. It would be so full of cars, you couldn’t park. They had a big walk-in screen outdoors. You’d pay a dime for a movie.” He paused. “Then the shops began to close down. One by one, they just closed.” Another long pause. “The morals and values are gone, too.” Williams is now a bedroom community of people who are retired or work elsewhere.

To understand where Williams’s farming wealth went, drive a few minutes out of town. You can see them on Google’s satellite view, dotted around the countryside: long buildings with shiny roofs, often side by side in twos, threes, or fours. These are CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, sometimes called factory farms. In each one, thousands of pigs (or tens of thousands of chickens) are packed tightly together in stinking ammonia-laden darkness, stuffed with antibiotics, their manure falling through slatted floors, and coalescing in pits where it rots anaerobically into a toxic stew that is then spread on fields as fertilizer, raising a stinking haze that can send nearby residents fleeing indoors. This animal sewage also pollutes local water sources. Much of it ends up in the Gulf of Mexico, where the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration warned last June that it contributed to a dead zone (an area devoid of marine life) about the size of New Jersey.

While this environmental damage is fairly well-known, the economic impact of CAFOs is less so. As they have spread, the number of hogs in Iowa has roughly doubled, from 15 million in the early 1980s to about 24 million today. (That paradox again: more pigs, poorer communities.)

The CAFOs inflict economic damage in stages. First they corrupt or destroy markets, the lifeblood of business. In 1993, nearly 90 percent of hogs were sold on competitive markets, according to the Open Markets Institute. Meat-packers “had to run around the countryside looking for pigs to keep their plant running,” said Iowa farmer Chris Petersen, one of the few independent pig farmers still operating. “Some days you got more money than others because they wanted those pigs real bad.” But today over 90 percent of American hog farming is controlled by large, vertically integrated meatpacking conglomerates. Farmers often must accept very low prices for their pigs.

Another problem is that while CAFOs can yield gushers of economic profit, the CAFO farmers themselves don’t usually see those returns. They are often just hog house janitors, as some call them, tied up by punitive contracts with the large firms, which, as Cedar Rapids lawyer Tom L. Fiegen put it, are “pages of things that shift the risk from the [agribusiness firm] to them.” There is “basically no choice” in the contracts. “Everything is dictated.” According to Fiegen, farmers typically take out large debts to finance the buildings, leaving them utterly dependent on the large firm to supply enough piglets to raise (then take away as grown pigs) at a per-animal price that the farmers must accept. The CAFO farmers’ constant anxiety about making the interest payments on their loans adds to the large firm’s leverage, enabling it to pare farmers’ income down to the lowest level they can survive on and remain on the farm. (The median farm income from hog farming was negative in 2018.)

Agribusinesses typically have the power to squeeze out for themselves some, most, or perhaps all of the federal agricultural subsidies that farmers receive. And financial shareholders constantly demand that the corporations squeeze hard. “People brag about the free market,” said John Ikerd, a professor emeritus at the University of Missouri and an expert in farm economics. “But we have central planning here—it’s just not by government. It’s by corporations.” Many people are eating into their farm’s equity simply to stay afloat, unwilling to be “the one who lost Grandpa’s farm.”

A third issue affects Williams even more directly. Decades ago, most agricultural wealth used to remain in Midwestern farming communities. Farmers bought seeds, implements, vehicles, and insurance from local suppliers and used local veterinary services, banks, shops, and restaurants. They wrangled agricultural wealth from soil, rain, and sunshine, and this wealth circulated in the community, supporting local prosperity. But then, especially since the 1980s, those local circulatory systems for money were systematically undermined. As anti-monopoly laws weakened from the Reagan era onward, big firms began to buy up and lock up the whole food chain—from pig semen all the way to your dinner plate. They took those farm services in-house, bypassing local providers. The big firms may, for example, replace community banks with bigger Wall Street players. “They probably don’t use a local lawyer. They may not need a local seed dealer. They may not need a local tractor dealer. And on and on and on,” explained Patty Lovera, formerly of the advocacy group Food & Water Watch. “Multiply that out,” and you get a “withering away of the economic ecosystem of real communities. Then maybe the post office shuts down. Then the hospital closes, and then the school closes. Then young people don’t want to stay there. And it’s kind of this sad sequence of events.”

Those local circulatory systems for money were replaced by one-way conveyor belts shipping rural wealth out, typically to metropolitan centers like New York and Chicago (and even to cities like Des Moines, whose economy now relies heavily on finance and insurance).

We can widen this frame. It isn’t just hogs; it’s beef, poultry, dairy, and grains. It’s the inputs: feed, seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, even the genes, which are now often locked up under powerful patents controlled by a few merged giants. It’s farm logistics: the derivatives brokers, commodity trading companies, supermarkets, pet food stores, even the restaurants you visit. Each is muscling its way to grab a bigger share of the money we all spend on food, constantly merging and all worrying about corporate giants like Amazon and Walmart. From the 1960s to the ’80s, about a third of each dollar American shoppers spent on groceries went back to farmers; in 2016, according to the Farm Bureau, that has fallen to less than 13 cents per dollar. Given total US food spending of about $1.7 trillion each year, that falling share suggests that the changes in the food system could be costing US farmers at least $150 billion a year—certainly many times the $18 billion in federal farm subsidies that were paid to them in 2018.

Where is all this hidden money going, and who benefits? To find answers, it helps to return to the finance curse that I mentioned earlier. This has two core elements. The first is another apparent paradox: that too much finance in an economy can make it poorer. This is related to the farming paradox I mentioned, and it can be explained via the second element, which goes as follows.

Finance isn’t just another economic sector, separate from the rest of the economy—it’s intimately plugged into it. Partly, this symbiotic relationship involves deposit taking, lending to real businesses, and other useful stuff. Another part involves wealth extraction, like what I’ve described in agriculture. Think of the wealth on Wall Street like the bag of a vacuum cleaner. The bigger the bag gets, the more profit has been sucked out of somewhere else. The rising fortunes and high share prices on the Street for agribusiness firms are essentially the flip side of poverty in places like Williams. And these tides of extracted wealth flow not just to Wall Street; plenty flow overseas or into offshore tax havens. Two of the five biggest meatpacking companies in the United States are JBS, a Brazilian firm with a long record of corruption, and the Chinese-owned Smithfield Foods, which is substantially influenced by the Chinese government.

Mike Callicrate, a rancher and businessman who campaigns against the power of Big Agribusiness, called this a “tapeworm economy,” which takes wealth and life from farming communities under “intense Wall Street/investor pressure.” (He wrote an article for The Washington Post in 2018 decrying “the boot of big agribusiness on your neck” and received dozens of angry comments, often based on the same misunderstandings as those about Martinmaas. “Right now,” Callicrate told me wearily, “we’re so darn easily divided.”)

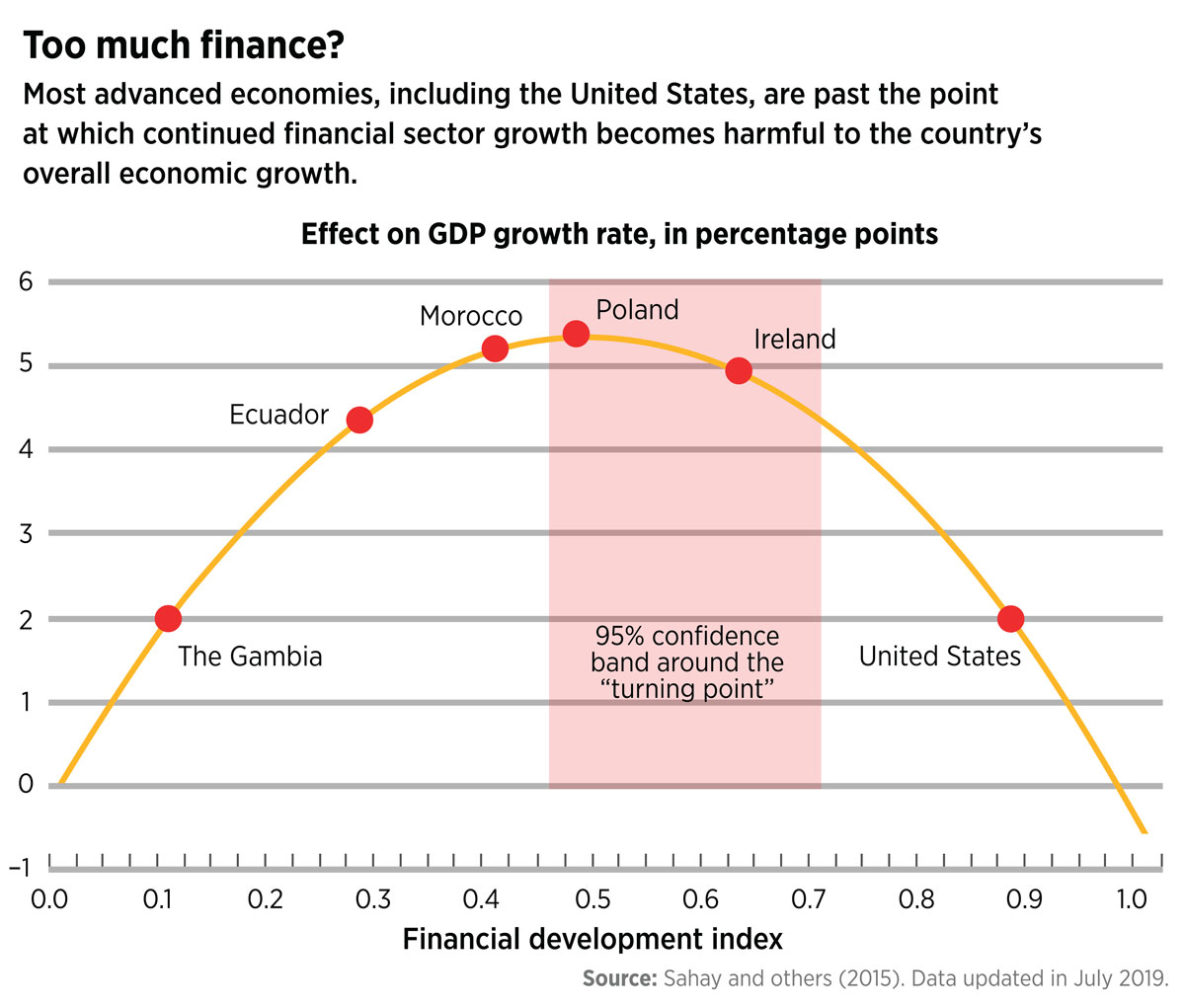

Crucially, this extraction doesn’t just cut the pie unfairly but shrinks it overall. A range of studies by the International Monetary Fund and others in the past decade have made a novel discovery about finance. After examining the relationship between the size of the financial sector and long-term economic growth in countries around the world, they generated several versions of the same bow-shaped graph, rising to a peak and then falling sharply. These studies show that once a financial sector grows beyond an optimal point—the United States seems to have passed it in the 1980s—further growth in finance tends to reduce overall economic growth. (I am British, and the very same thing is happening in my country.) According to a 2016 study by professor Gerald Epstein and Juan Antonio Montecino at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, an oversized financial sector will have cost the US economy $13 trillion to $23 trillion from 1990 to 2023, or $100,000 to $184,000 per family. That suggests how much richer America might have been had finance remained at its optimal smaller size, performing useful functions without its predation on agriculture and other sectors of the economy.

Financial extraction happens across the economy, from farming to health care to retail to manufacturing and beyond. The tools include building monopolies, using tax havens to cheat on tax bills, firms channeling profits not into productive investment but into buying back shares to boost share price (and their CEOs’ stock options), private equity moguls buying healthy companies and then forcing them to borrow billions and pay the proceeds straight to them, and bankers profiting from taking large risks and then begging for bailouts when those risks lead to financial crisis. Imagine each tool as an invisible siphon jammed into our pockets, steadily sucking out coins and notes, channeling them into the big money centers and offshore tax havens. None of this boosts genuine productivity or entrepreneurship.

The financial sector doesn’t just extract money. High pay also draws talented people out of other economic sectors and out of government, harming us all. As a landmark global study by economists Stephen G. Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi put it, “Finance literally bids rocket scientists away from the satellite industry. The result is that erstwhile scientists, people who in another age dreamt of curing cancer or flying to Mars, today dream of becoming hedge fund managers.” Bring the costs of the global financial crisis into this bad equation, and you’ve got a powerful explanation for why oversize finance undermines prosperity.

How do we fix this? Surprisingly, that’s the good news. People fret that there’s a trade-off between popular policies, such as higher taxes on billionaires, and economic prosperity. Tax or regulate them too much, goes the worry, and these clever folk will stop investing. But once we reveal the wealth creators as financial parasites, the ugly trade-off disappears. We can bring back democracy, and America will be wealthier for it. Imagine directing those outward-moving conveyor belts of wealth back to farm country, pumping a big chunk of that lost $150 billion into the shops, businesses, and wallets of rural Americans. This may not bring millions of farmworkers back to the countryside. But it would—if combined with modern high-tech farming methods—make sustainable family farming a vastly more viable proposition, reinvigorating rural communities.

To advance this progressive agenda, people must see that the coming economic battle is not between rural America and those “coastal elites.” Nor does it pit “whining and begging” farmers against consumers and taxpayers. In reality, those angry Washington Post commentators (unless they are very rich) stand alongside farmers like Ray and Becky Martinmaas in a shared struggle against oversize, globalized, monopolized, subsidized Big Finance and its many tools for extracting wealth from the food system. That’s where the really big handouts go. This fight can bring together people across the political spectrum, including many who voted for Trump or stayed home in 2016. It’s exciting that political candidates are now, finally, joining the battle on this terrain.

Original article: Rural America Doesn’t Have to Starve to Death | The Nation