Parched: A New Dust Bowl Forms in the Heartland

Parched: A New Dust Bowl Forms in the Heartland

"Exceptional drought" makes for tough times in Oklahoma.

A farmer walks in a dust storm on drought-stricken lands near Felt, Oklahoma, on August 1, 2013.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ED KASHI, VII

Laura Parker

Published May 16, 2014

In Boise City, Oklahoma, over the catfish special at the Rockin’ A Café, the old-timers in this tiny prairie town grouse about billowing dust clouds so thick they forced traffic off the highways and laid down a suffocating layer of topsoil over fields once green with young wheat.

They talk not of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, but of the duster that rolled through here on April 27, clocked at 62.3 miles per hour.

It was the tenth time this year that Boise City, at the western end of the Oklahoma panhandle, has endured a dust storm with gusts more than 50 miles per hour, part of a breezier weather trend in a region already known for high winds.

"When people ask me if we’ll have a Dust Bowl again, I tell them we’re having one now," says Millard Fowler, age 101, who lunches most days at the Rockin’ A with his 72-year-old son, Gary. Back in 1935, Fowler was a newly married farmer when a blizzard of dirt, known as Black Sunday, swept the High Plains and turned day to night. Some 300,000 tons of dirt blew east on April 14, falling on Chicago, New York, Washington, D.C., and, according to writer Timothy Egan in his book The Worst Hard Time, onto ships at sea in the Atlantic.

"It is just as dry now as it was then, maybe even drier," Fowler says. "There are going to be a lot of people out here going broke."

The climatologists who monitor the prairie states say he is right. Four years into a mean, hot drought that shows no sign of relenting, a new Dust Bowl is indeed engulfing the same region that was the geographic heart of the original. The undulating frontier where Kansas, Colorado, and the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma converge is as dry as toast. The National Weather Service, measuring rain over 42 months, reports that parts of all five states have had less rain than what fell during a similar period in the 1930s.

A gigantic dust cloud looms over a ranch in Boise City, Oklahoma, in this April 1935 file photo.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AP

"If you have a long enough period without rain, there will be dust storms and they can be every bit as bad as they were in the Thirties," says Mary Knapp, the Kansas State assistant climatologist.

Cattle are being sold to market because there is not enough grass on rangeland for large herds to graze. Colorado’s southeast Baca County is almost devoid of cattle—a change that Nolan Doesken, Colorado’s state climatologist, calls "profound and dramatic."

Elsewhere, drifts of sand pile up along fence lines packed with tumbleweeds, and tens of thousands of acres of dry-land wheat have died beneath blankets of silt as fine as sifted flour. In the vocabulary of Plains weather, this is known as a "blowout." Blowouts often start as brown strips along the outer edges of fields, and then spread with each successive blowing wind like a cancer.

"Once your neighbor’s fields starts to blow, it puts your own fields at risk," says Gary McManus, Oklahoma’s state climatologist, who toured the blown-out wheat fields outside Boise City last week.

High winds and a record-breaking heat wave led to damaging erosion in this unplanted cotton field.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBB KENDRICK, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

Hotter and Drier

McManus, 47, grew up in the panhandle town of Buffalo, where his grandparents gave up farming during the drought of the 1950s and moved to town. He has a special affinity for the panhandle, which he says is often ignored by state officials and is in worse shape as a result of the present drought than any other part of Oklahoma. Part of his job involves traveling Oklahoma’s back roads to speak to farm groups. In the past three years, as the drought settled in, he has given 100 talks to farmers, 40 of them about the drought.

"They want to know what’s going to happen," he says. "Are we going to get moisture for my wheat? My answer, generally, has been probably not. Unfortunately, I’m right more often than I’m wrong."

The farmers also ask for a long-term forecast, which takes McManus into the politically perilous realm of climate change, a touchy subject in a state where Republican Senator Jim Inhofe is known as one of the leading congressional voices denying global warming and where, as one man put it, what farmers believe depends on "whether they listen to FOX or CNN."

"It’s not a subject I like to speak about. It’s nerve-wracking," McManus says. "I am often met with skepticism, and I tell them I am just presenting the science."

According to the National Climate Assessment, the government’s interagency report detailing the impact of climate change, the science shows that the region is trending toward hotter and drier. The longer the current drought lasts, the harder it will be to recover. A quarter of Oklahoma, including the panhandle, and neighboring counties in Kansas and Texas are rated as being in "exceptional drought," the driest category on the weekly U.S. Drought Monitor—a status so dry that farmers express relief whenever their standing moves incrementally up a notch to "extreme drought."

As of the end of March, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ranked 42 percent of Oklahoma’s winter wheat crop as "poor" to "very poor," and categorized almost three-quarters of the state’s topsoil as "short" of moisture and 80 percent of the subsoil as "very short" of moisture.

A man stoops over a row of scraggly corn in an open field in June 1938 in Colorado. The corn in the field behind him, protected by trees, is much healthier.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AP

The Best Bad Option

Nathan Crabtree, vice president of First State Bank on Main Street, says high commodity prices, together with the federal crop insurance program, which pays 70 percent on averages of annual yield, has saved more wheat farmers from going under than he can count. "If we had $4-a-bushel wheat, instead of $8-a-bushel wheat, we’d be in serious trouble," he says. "Crop adjusters are out here every day, looking at fields," he says. "Most of them are going to be zeroed out."

There is no drought insurance for cattlemen. Herds with strong bloodlines built up over generations are being liquidated. "It’s like they’re selling their own kids," he says.

Hal Clark, 82, a rancher, is trying to kill non-native, water-gorging weeds on his grazing land, so there will be more for the grass to absorb. Kenneth Rose, 68, a dry-land wheat farmer and cattleman, has sold off half his herd and is trying to salvage his wheat crop. He has two options, both bad.

The best bad option, he says, seems to be plowing deep furrows, as was done in the 1930s. This churns up big clods, which weighs down the soil and creates ridgelines to break up the wind. He calls it a "desperate measure," because if it doesn’t rain this year, the field will be drier than ever next year and unsuitable for planting.

The other option is to let his fields lie and blow now.

"What are you gonna do?" he says. "It’s discouraging at times, but part of living here. I’ve got too much invested to quit now."

Workers drill for water in Felt, Oklahoma, on July 28, 2013. Because of ongoing drought, overdrilling for water is depleting the Ogallala Aquifer.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ED KASHI, VII

"One Day Closer to Rain"

Boise City is the county seat of Cimarron County, Oklahoma’s westernmost county, and a remote area still known as No Man’s Land. The moniker refers to the panhandle’s status in the mid-1800s as an unclaimed territory that became an enclave for outlaws and thieves. Today, the name refers more to its isolation: Boise (pronounced BOYCE) City is closer to the capitals of Colorado and New Mexico than it is to its own statehouse in Oklahoma City, 326 miles to the east.

In a bit of geographical irony, the town’s name derives from the French le bois, meaning "the trees." At its turn-of-the-century founding, land hustlers sold lots to homesteaders on the promise of paved streets lined with elms, ample water, and a railroad stop connecting the lonely outpost to civilization in the East. When the new arrivals discovered the sales pitch was fiction, the hustlers ended up in prison for fraud. But the town endured, as the newcomers eagerly joined what became known as the great plow-up that transformed millions of acres of native grassland into farmland, setting the stage for the worst ecological disaster in the nation’s history.

Today, the only elms are those planted as wind breaks, and they are dying by the thousands.

Girls cover their faces during a swirling dust storm while trying to pump water in Springfield, Colorado, in this March 1935 file photo.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AP

The drought of the Thirties lasted a decade. Despite the great exodus of "Okies" to California, mythologized in John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, most people in the Southern Plains stayed. They were tough and resilient, and still are. They adapted to the harsh, unyielding land they farmed, devising new farm techniques to help the soil recover.

Since 1985, the National Resources Conservation Service, run by the USDA, has been paying farmers with badly eroded land to take it out of production and grow native grasses instead.

"You have to be an optimist to be a farmer," says Iris Imler, programs coordinator of the Cimarron County Conservation District, which partners with the USDA to assist farmers and ranchers. "You know the saying in a drought—we’re one day closer to rain."

A rancher herds his cows on horseback from the pasture to the barn in Felt, Oklahoma, on July 30, 2013.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ED KASHI, VII

A Hard Pull

Still, life on the Plains remains a hard pull. Towns across the prairie continue to lose population. Boise City has declined by 18 percent since the 2000 Census. The population hovers today around 1,216. Kids grow up and go off to the city because, as nearly everyone will tell you, the only jobs in the area are those in agriculture and those are few and getting fewer.

There has been talk, Imler says, of harnessing the panhandle’s most reliable resource—the wind, as energy companies in Boise City’s neighboring counties in Texas and Kansas have done. But Oklahoma’s electrical transmission line ends 60 miles short of Boise City, creating an obstacle that only the state legislature can resolve. Which isn’t likely to happen any time soon.

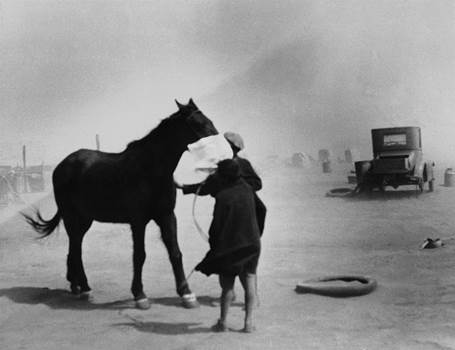

People use a towel as a dust mask for their horse in this file photo taken in eastern Colorado.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AP

Meanwhile, a new agricultural industry has materialized. The water-consumptive hog business moved into the Oklahoma panhandle in the 1990s, drawn in part by Oklahoma’s lack of regulations and restrictions on water taken from the Ogallala Aquifer, the vast underground reservoir that underlies the Great Plains and provides 80 percent of its drinking water as well as irrigation for thirsty crops like corn. Texas and Kansas both limit draws on the aquifer. At the time, farmers in Boise City expressed concerns about the impact on water supply, but the Seaboard Food plant revived the dying town of Guymon, in next-door Texas County.

Bart Camilli, who farms 2,400 acres of dry-land wheat, thinks the dropping water table in the Ogallala is a far more significant threat than global warming. "I put no stock in climate change, but I worry every day about the Ogallala," he says. "That will be the biggest factor affecting this county. What happens to the Ogallala makes this drought pale by comparison."

Tumbleweeds pile up around an abandoned farm in Haswell, Colorado, on April 1, 2014.

PHOTOGRAPH BY RJ SANGOSTI, THE DENVER POST/GETTY

"Dwindling Communities"

Another glimpse of the future can be seen at Oklahoma Panhandle State University, on the outskirts of Goodwell, an hour’s drive east. For most of its history, the school, founded in 1909 as a small, agricultural college, drew students from a 250-mile radius.

The shrinking prairie population has changed all that, forcing administrators to hunt for students farther afield. "It has been very difficult to maintain enrollment because of dwindling communities and competition from other schools," says Larry Peters, a college vice president who worked on his family’s farm.

As insurance, OPSU has also added new disciplines, including computer technology, business, and nursing, now the fastest-growing program of study.

This abandoned farm in Haswell, Colorado, is pictured on April 1, 2014.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ALFRED EINSENSTAEDT, TIME AND LIFE PICTURES/GETTY

Curtis Bensch, who heads the agronomy department, says the small family farm is all but a thing of the past. Jobs that await his graduates include positions in corporate farming, the hog industry, and the fertilizer business.

The college also is home to a research station for Oklahoma State University, which develops new drought-tolerant strains of wheat such as one called "Duster" and is experimenting with the development of a subsurface irrigation system to cut down on evaporation.

"Hog operations do have high water demands, but so does irrigating cropland," Bensch says. "I think the consensus is that agricultural enterprises are going to continue to use water as efficiently as they can, but realistically, there will probably come a day when they just don’t have the water to do what they used to do."

Brad Duren, a history professor, says many of his students are preparing to become teachers, but are concerned about finding teaching jobs as tiny school districts that dot the Plains disappear.

Most of the students on campus are children of the 1990s, a wetter-than-usual decade. Unnerved by the dust storms, they retreat into the sensibility of youthful inexperience and the belief that technology has a solution for every problem.

"Students all too often regard history as that was then, and because this is 2014, and because we have iPhones, we’re smarter than the people who lived in the 1930s," Duren says. "They have this faith in science and technology that everything is going to be okay. But we live in a harsh environment. The problem is, when you run out of water, there are only so many ways to get more."