Food & Power: Colluding Pork Packers Accused of Pigging Out On Profits

July 19, 2018 | Get your own copy by subscribing here.

Since roughly 2009, Americans may have been paying too much for their pork chops, barbeque, hams, and trotters.

That’s the claim of two law firms that filed separate class action suits on behalf of consumers and food distributors charging eight major pork packers and an industry data sharing service, Agri Stats, with colluding to manipulate prices.

The case comes more than a year after dominant chicken packers were charged with an identical crime. In both cases, the suits argue that Agri Stats’ detailed, company-specific, and forward-looking data made it possible for pork processing companies to coordinate the supply of pork, and critically, monitor one another’s behavior to ensure no one in the cartel deviated from their conspiracy.

Hormel and Smithfield have denied the price-fixing allegations. A representative from Tyson, also a defendant in the poultry case, said in an email, “We intend to vigorously defend against the allegations in court.” Other defendants have not commented.

The suits allege that collusion began around 2008 when Agri Stats started to market pork “benchmarking” reports, which compare data from pork meat packers on everything from total profits and hogs slaughtered, to farm-level data about feed ratios, mortality rates, piglet weaning costs, and so on. By 2016, Agri Stats benchmarking reports collected and internally audited information from over 90 percent of the pork industry.

“Once Agri Stats got everyone in the pork industry to put their card on the table, there was no competition,” said Steve Berman, managing partner at Hagens Berman, one of the firms suing pork producers, in a public statement.

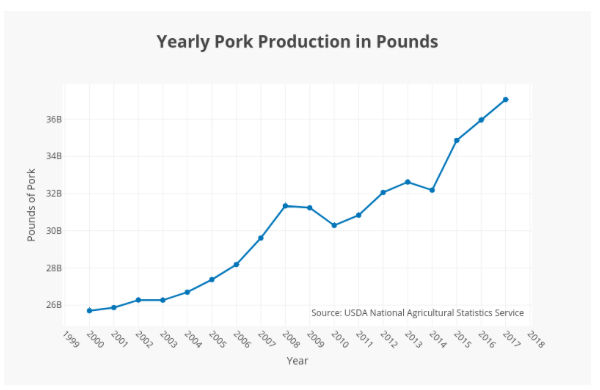

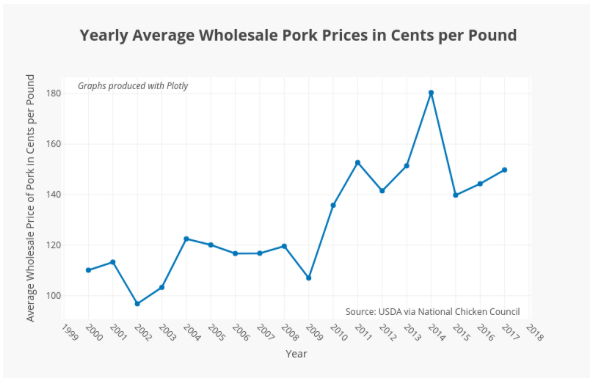

Pork production stagnated and prices increased almost immediately after pork corporations began using Agri Stats benchmarking data. Between 1998 and 2009 the year average price per hundredweight of pork was never more than $50. But from 2009 to 2014, prices rose over 50 percent to $76.30. This was true even though the price of other agricultural commodities started to fall around 2012 and 2013. Annual pork production fell in 2009, 2010, and again in 2013 (with another dip in 2014 due to disease).

The plaintiffs argue that pork corporations coordinated changes in production with the help of Agri Stats. However, this claim raises the question, what makes Agri Stats different from other industry data service companies or market information provided by the USDA?

Darren Tristano, the CEO of a foodservice and hospitality data research service, CHD Expert, says market reports with un-aggregated, company-level information are “very rare.” Indeed, the pork suit claims that “Agri Stats’ reports are unlike those of other lawful industry reports,” in that they provide “current and forward-looking sensitive information” broken down by company and even farm. All of this data is anonymous, but the suit contends that Agri Stats reports contain “the keys to deciphering which data belongs to which producers.”

This key difference, in turn, could allow conspirators to tie specific data back to individual companies and identify any one who tried to cheat the others by not adhering to their price-fixing plan. Without frequent, audited, and disaggregated data from Agri Stats, the suits argue, large pork companies could not be sure that all conspirators were cooperating.

Furthermore, in a decentralized market of many independent pork producers, collusion on the scale in question would be almost impossible to coordinate, even with the help of an especially detailed data service. Yet today, four companies sell just under 70 percent of all pork, making collusion comparatively easy.

Pork packers also have unprecedented ownership over all steps in the supply chain, from breeding to feed production and slaughter, while individual farmers take on the risk of raising hogs on contract for large corporations.

While the new suits focus on the impact of the conspiracy on pork buyers, Agri Stats data-sharing also raises questions about potential harms to hog growers. A 2017 lawsuit filed on behalf of poultry growers claims that poultry processors used Agri Stats to share data on farmer compensation. The suit argues that poultry processors worked together to “[depress] Grower compensation below competitive levels.”

Such a suit has not been filed on behalf of hog farmers, and neither of the current pork price-fixing suits makes mention of Agri Stats providing data on hog grower compensation.

The pork suits do argue that hog farmers bore the brunt of price variations over the course of the alleged conspiracy. Hog farmer earnings plummeted in 2014, and have since failed to bounce back to 2010-2013 levels. Meanwhile, pork packer earnings grew precipitously from 2012 onward, with only a slight dip this past year.

Intentional wage suppression or not, these cases highlight the immense power that a handful of vertically integrated meat companies have to force farmers to assume all the risk, to increase prices for consumers, and to hog the benefits for themselves.

Special Legislative Update: Checkoff Reform Bill Fails, But Vote Shows Bipartisan Support (and Opposition)

On June 28th, the Senate voted down an amendment to the U.S. Senate Farm Bill, sponsored by Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ), Mike Lee (R-UT), Rand Paul (R-KY), Maggie Hassan (D-NH), and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), that would have better prevented federal checkoff programs from using their funds to influence legislation and brought greater transparency into how funds are allocated. Despite bipartisan support, the resolution failed 57 to 38.

Checkoff programs were established to help research and market agricultural commodities. Farmers pay mandatory fees to federal industry-specific boards, which manage these funds. Checkoff programs are legally required to benefit all participating farmers. But as detailed in this newsletter and this article in the Washington Monthly, these funds have repeatedly been used to support lobbying efforts and influence legislation that disproportionally benefits the largest producers.

Among the YEAs were Senators McCaskill (D-MO), Gillibrand (D-NY), Grassley (R-IA), Flake (R-AZ), Tester (D-MT), Harris (D-CA), Rubio (R-FL), and Cruz (R-TX). By party, the YEAs were 63 percent Democrat and 34 percent Republican.

Among the NAYs were Senators Roberts (R-KS), Stabenow (D-MI), Feinstein (D-CA), Baldwin (D-WI), Heitkamp (D-ND), Klobuchar (D-MN), McConnell (R-KY), Ernst (R-IA), Boozman (R-AR), and Perdue (R-GA). By party, the NAYs were 35 percent Democrat and 63 percent Republican.

An overwhelming 76 percent of the Senate agricultural committee voted against the measure.

You can find the full voting record here.

What We’re Reading

- Beginning July 31st, about 1,700 farmers markets will no longer be able to process SNAP transactions. As the Food and Environment Reporting Network and Washington Post report, a software company that helped farmers markets process mobile federal benefit transactions, Novo Dia, is shutting down. A lack of alternative software for Apple users and a waitlist for new processing equipment could mean some markets will not be able to accept SNAP benefits until August, at the earliest.

- Many residents of the southeastern state of Chiapas, Mexico have been drinking Coca-Cola instead of water, as the local water utility now only delivers water a few times a week. By contrast, as the New York Times reports, the Coca-Cola plant itself enjoys a permit to extract 300,000 gallons of water a day, and further can count on a contract with the federal government to pay just 10 cents per 260 gallons of water. Critics in the town of San Cristobal argue Coca-Cola should instead pay local governments to help rebuild the failing infrastructure that serves residents. The mortality rate from diabetes in Chiapas increased 30 percent between 2013 and 2016.

[…] References: https://www.meatpoultry.com/articles/24751-jbs-usa-agrees-to-20m-settlement-in-pork-price-fixing-lawsuit https://www.agristats.com https://www.porkbusiness.com/news/industry/jbs-usa-settles-third-pork-price-fixing-lawsuit https://lawstreetmedia.com/agriculture/analytics-how-the-meat-industry-leads-to-dozens-of-antitrust-lawsuits/amp/ https://lawstreetmedia.com/agriculture/defendants-question-applicability-of-recent-decision-to-pork-antitrust-lawsuit/amp/ https://news.mikecallicrate.com/food-power-colluding-pork-packers-accused-of-pigging-out-on-profits/ […]

[…] References: https://www.meatpoultry.com/articles/24751-jbs-usa-agrees-to-20m-settlement-in-pork-price-fixing-lawsuit https://www.agristats.com https://www.porkbusiness.com/news/industry/jbs-usa-settles-third-pork-price-fixing-lawsuit https://lawstreetmedia.com/agriculture/analytics-how-the-meat-industry-leads-to-dozens-of-antitrust-lawsuits/amp/ https://lawstreetmedia.com/agriculture/defendants-question-applicability-of-recent-decision-to-pork-antitrust-lawsuit/amp/ https://news.mikecallicrate.com/food-power-colluding-pork-packers-accused-of-pigging-out-on-profits/ […]