Des Moines Register: EXCLUSIVE: Elizabeth Warren lays out plan to target corporate agriculture, support family farms

by Brianne Pfannenstiel and Kim Norvell, Des Moines Register | March 27, 2019

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren is taking aim at some of the nation’s largest agribusiness companies, such as Tyson and Bayer-Monsanto, continuing her campaign’s assault on corporate consolidation.

The Democratic presidential candidate’s plan, released exclusively to the Des Moines Register before it was unveiled Wednesday, would address consolidation in the agribusiness industry, “un-rig” the rules she says favor its largest players, and elevate the interests of family farmers.

“We can make better policy choices — and that means leveling the playing field for America’s family farmers,” Warren wrote in a Medium post outlining her proposal.

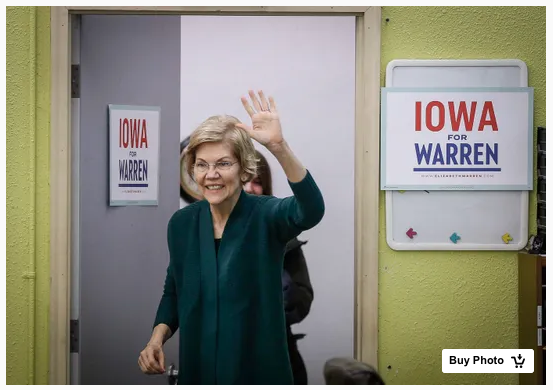

Warren has not shied away from confronting those affected by her policies, delivering them directly to those industries’ doorsteps. Just as she announced her plan to break apart the nation’s largest tech companies before heading to one of the industry’s largest gatherings, Warren is announcing her plan to take on corporate agriculture days before traveling to Iowa to speak at a rural issues forum.

The companies she names in her plan — Tyson, Dow-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto — are some of the key players in Iowa’s economy.

Warren’s campaign has focused on the idea that the federal government no longer works for working families and small businesses but instead is rigged in favor of the wealthy and well-connected. The senator has separated herself from a crowded field of Democratic contenders early in the race by releasing multiple policy proposals shaped around those themes.

The policy she is unveiling Wednesday follows in that same vein but more closely touches Iowa, where nearly 90 percent of the state — roughly 30 million acres — is covered in farmland.

Rural Iowa, in particular, has felt the effects of farm consolidation, which creates ripple effects through local economies. According to data for the U.S. Agriculture Census, Iowa lost 32,600 farms during a 30-year period that ended in 2012.

Austin Frerick, a Democrat who ran for Congress in Iowa’s 3rd District in 2018 primarily on the issue of breaking up agricultural monopolies, said plans like Warren’s have the potential to revitalize rural communities.

“Putting more bargaining power in farmers’ pockets means more money for farmers. It means more money in these communities and small Iowa towns,” he said.

Frerick, a former economist at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, was among the people from whom Warren’s campaign sought input as it drafted the proposal.

“People are so happy in rural Iowa to see a Democrat talking farm and ag policy, who knows what the price per bushel is, who knows their pain,” Frerick said. “Because Democrats just lack a vision for agriculture right now.”

In the Medium post, Warren argues small farmers are unable to get ahead “because bad decisions in Washington have consistently favored the interests of multinational corporations and big business lobbyists” over their own.

“Iowa feels this very directly,” Warren said during a recent interview with the Register in which she discussed the ways monopolies and near-monopolies are “fundamentally changing our economy.”

“The number of purchasers of soybeans or hogs has shrunk dramatically,” she said. “The number of seed providers has shrunk dramatically, and the diversity of the seeds (offered) has shrunk. Concentration in those industries has put a real squeeze on small- and medium-sized farms in Iowa.”

She is calling for a reversal of the $66 billion merger between Bayer AG and Monsanto, which was approved by federal regulators earlier this year.

At the time of the merger, Monsanto operated facilities in Grinnell, Williamsburg, Huxley and Ankeny that employed 2,356 workers in Iowa. Warren and other antitrust experts argued the merger would eliminate competition between two of the largest players in the seed industry and give the company lopsided control over the market.

The merger gives Bayer-Monsanto control of a quarter of the world’s seeds and pesticides market.

Warren’s proposal names Tyson — which employs more than 9,000 people in Iowa — in calling for the breakup of companies that have started to control nearly all aspects of farming, including feeding, slaughtering and transporting. The Department of Justice has not revised its guidelines on these types of vertical mergers in 35 years, Warren notes.

“Chicken farmers have gotten locked into a ‘contract farming’ system in which they take on huge risks — loading up on debts to build and upgrade facilities — while remaining wholly dependent on Tyson for everything from receiving chicks to buying feed to selling the grown broilers,” she wrote.

Warren’s policy announcement precedes a planned trip to Storm Lake, Iowa this weekend, where she’ll rally with family farmers and attend a forum focused on rural issues. Warren is scheduled to appear alongside fellow presidential candidates Minnesota U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, former U.S. housing secretary Julián Castro and former Maryland U.S. Rep. John Delaney. Ohio U.S. Rep. Tim Ryan, who is considering a run, also will speak.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders had been listed as a guest to the forum, but, according to organizers, will not attend. While he campaigned in Iowa earlier this month, Sanders also criticized large factory farming and the merger between Bayer and Monsanto.

“I pledge to you to do everything I can to restore the well being of rural communities all across this country,” he told a crowd in Iowa City.

Others, like New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, also have addressed on the issue while campaigning in Iowa. Booker has introduced legislation in the U.S. Senate that would end corporate ag consolidation and reform the industry checkoff program.

“I believe that we are all in this together — that what’s happened to the agriculture industry is hurting all of us,” Booker said at a February event in Mason City. “It’s hurting our environment. It’s hurting our family farmer. It’s hurting the consumers. It’s hurting the American way.

Warren’s plan would…

- Appoint federal regulators who would scrutinize mergers in the agriculture industry and reverse those that are anti-competitive.

- Break up agribusinesses that have become too vertically integrated — meaning they control multiple aspects of bringing a product to market.

- Pass a national “right-to-repair” law, similar to one introduced in Wyoming in 2017, that would let farmers repair their own equipment or take it to a mechanic, instead of requiring those repairs to be made at dealerships or authorized agents.

- Give farmers the choice to participate in the so-called “checkoff program,” which requires producers to pay a portion of their sales for promotion and research of their products. The checkoff program has been responsible for commercial campaigns like “Got Milk?” and “The Incredible Edible Egg” but has been criticized for funding lobbyists of large corporations.

- End contract farming. Major companies like Tyson and Perdue hire contract farmers, which raise and care for the company’s product but are required to make expensive upgrades and investments to their farms. Those farmers then become reliant on processing companies for supplying livestock and buying feed.

- Establish new country-of-origin rules that would require beef and pork producers to label where their livestock was raised and slaughtered. Currently, companies can add a “product of U.S.A.” label to meat that was broken down and packaged in the United States but raised in another country. She would push for Mexico and Canada to adopt similar rules.

- Pass a national version of an Iowa law that dates back to the 1970s and forbids any foreign entity from purchasing agricultural land in the state for farming. Elsewhere, 27.3 million acres of farmland is owned by foreign investors, the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting found.