Daily Yonder: Pork, political sway and provoked communities

By Brian Bienkowski | January 19, 2018

Rural neighbors join forces against giant hog farms. But in state capitols, money talks.

Sue George’s home is pure country charm.

She shows me an enormous Norwegian pot that looks like a witch-cauldron hanging from her ceiling. We’re in a throwback country kitchen—complete with decorative plates and antique cutlery hanging on the walls.

“When I heard guests were coming I had to hurry and find something,” she says, putting pie and lemonade out.

“Oh that’s Master Luke and Princess Leia,” she says when I do a double take at the two ponies meandering outside the back window. The soft-spoken, retired second-grade teacher moves on to talk of her health struggles (“I had more pulmonary embolisms than they could count”). She stays cheerful until the topic turns to hogs.

Then the smile fades.

“My God I wasn’t prepared for this,” she says. She and her husband Jerry have led the organizing as this tiny community, population 485, has fought two large, indoor hog barns near the town over the past five years. Another one is under construction.

Lime Springs neighbors are active – they research, meet and educate. They put up signs and write editorials. But people like Sue George are up against a state beholden to livestock.

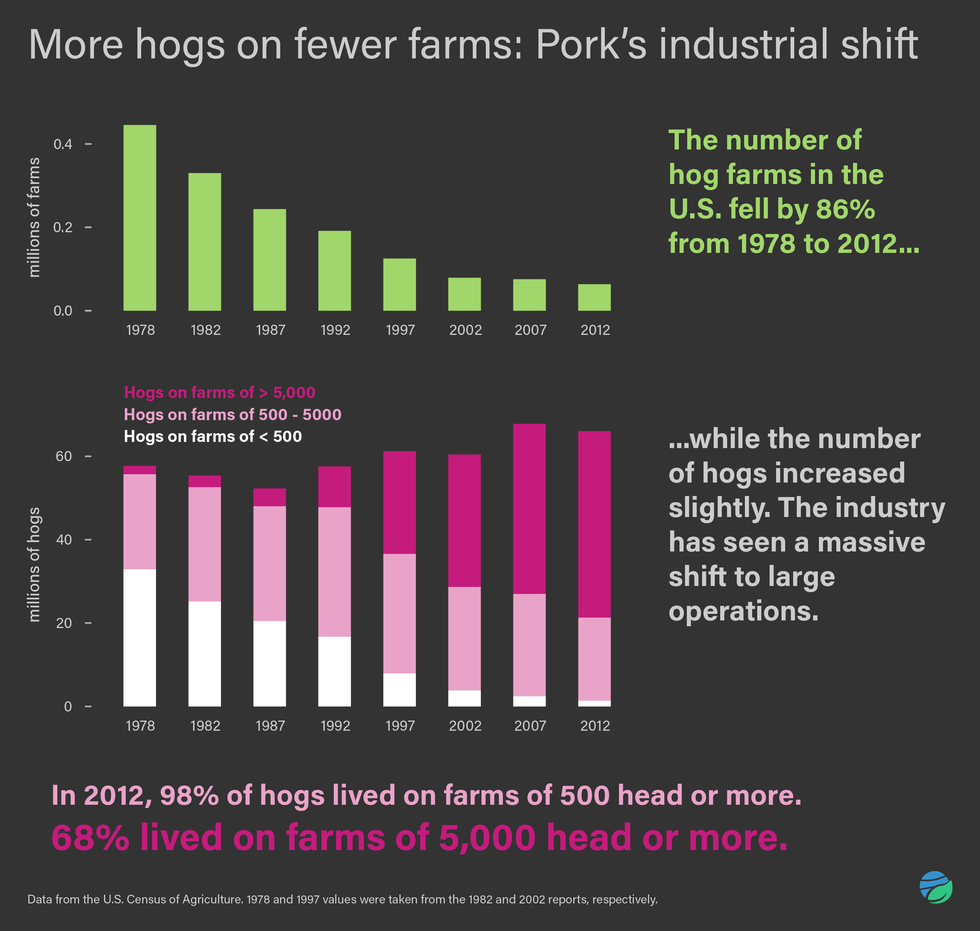

Local ability to stop big barns—which can hold upwards of 20,000 head of hog each—is non-existent; that power was long ago snatched away by the Legislature. An industry that employs thousands and pays a nice chunk of taxes each year gets handled with kid gloves; state lawmakers tend to look askance at environmental and social concerns over corporate consolidation and increasingly ramped up production.

Money talks in politics—and these days the pork lobby does a lot of talking in the state and federal Legislature.

Iowa has more than 6,300 hog farms and about 60 percent of them raise more than 1,000 hogs. At any given time in the state there are more than 20 million hogs—about 7 times the state’s population. Most are raised in confinement operations: Windowless barns where pigs are kept in individual stalls.

Sue George and the group she leads, Northeast Iowans for Clean Air and Water, say the state’s Department of Natural Resources’ enforcement is lagging. Rules are rigged for the hog owners. She worries the air pollution will worsen her breathing problems and the water near her farm, which has been in her husband’s family for more than 100 years, will be tainted.

“I never imagined doing activism,” she says, adding that there’s a community meeting happening later that evening at her house. She has to be careful how the gatherings are announced because she’s had hog confinement workers crash them in the past.

This effort is a David to the Goliath of the pork industry’s spending and political capital in Des Moines and Washington, D.C. As domestic and international taste for pork has grown, so, too, has the industry’s influence on local, state and national politics.

In the 2016 U.S. elections the meat industry (livestock and meat processing combined) contributed roughly $11.7 million to political campaigns, nearly triple what was spent 15 years prior.

And while Sue George and her neighbors plot in Lime Springs, hog farming corporate advocates are having meetings, too: In 2016 the industry spent $7.8 million on lobbying in Washington, D.C., that, too, is triple what was spent 15 years ago.

State lawmakers say the industry buoys the state. Its growth, they insist, is inseparable from rural well-being. “We raise livestock in Iowa and raise a lot of it,” says Rep. Chip Baltimore, a Republican from Boone, Iowa. “It’s a foundational building block of our state economy.”

The economic impact is undeniable. But rural folks living near the operations feel they’ve been left behind. And in living rooms, community centers and diners throughout the state, opposition is growing and organizers are looking to bring local voices back to state politics.

They demand better protections for clean air and water. They want counties and communities affected by hog operations to have decision-making power.

“When you’re cornered you can roll over and play dead, or you can use your voice,” George says.

The problem, in rural America today, is that those voices don’t have the strength they once had. Any attempt to reign in hog farming is met with entrenched resistance in the heavily Republican Iowa Senate and House.

Pork politics

Money in politics has drastically increased since the U.S Supreme Court’s 2010 “Citizens United ruling” and the growth of Big Agriculture influence is no different. Agribusiness contributed more than $110 million to political campaigns in 2016, a 43 percent increase from spending just a decade ago. About 73 percent of the money went to Republicans.

Small, family-run farms have become isolated, says Aaron Sherb, director of legislative affairs for Common Cause, a nonpartisan organization focused on government accountability. “This is problematic from a civic engagement perspective—whether it’s working on the federal Farm Bill, or at the state level.”

Sherb says the huge influx of corporate money, and corresponding influence, can lead to policies that favor the big corporations.

One striking example is the sugar industry, which has quite the head start on livestock in getting the ear of politicians, at least in Florida. Big Sugar contributed more than $57 million to state and local politicians in Florida over the past 20 years, not including federal contributions.

It seems to be working—in Florida the industry has avoided multiple attempts to acquire sugar cane growers’ land in the Everglades for cleanup, despite Florida voters approving a 2014 amendment to do so. Instead the Legislature steered the money toward other projects not including land acquisitions.

The sugar industry has dodged attempts by Florida voters calling for the industry to pay for nutrient pollution and the Legislature has repeatedly delayed water quality standard regulations.

Iowa’s gold is in swine, not sugar. But the same lessons apply. The National Pork Producers Council, the country’s main pork lobby, was Iowa’s biggest political contributor in the 2016 election cycle, according to records.

That investment is paying off. In the past two years alone the Iowa Legislature has:

- Bolstered the state’s anti nuisance law, limiting lawsuits by neighbors against nearby livestock.

- Shot down a petition—signed by more than a dozen counties—that would have given counties more control in hog farm siting.

- Cut funding to the Department of Natural Resources, including scrapping the agency’s animal feeding operations coordinator position.

Those changes can’t all be credited to the Pork Council. But their clout is undeniable. The Council spent $435,969 on contributions; the next largest contributor was the University of Iowa at $347,734. In addition 21 of the 34 National Pork Producers Council lobbyists in 2016 previously worked in government jobs.

As the industry has grown so has its lobbying. The Council spent an additional $1.64 million on lobbying nationally—a 382 percent increase over lobbying spent just 15 years ago.

Chris Petersen, an Iowa hog farmer and agricultural activist, says the Pork Council, like the Iowa Farm Bureau and other institutions that once helped people like him, are now advocating for what most benefits the large corporate farmers.

Those interests don’t always align.

“I stand with the Farm Bureau on property rights,” he says. “But where we part is when what you’re doing on your property affects my health and that of my land.”

The state’s Farm Bureau spent $224,000 in 2016 campaign contributions, a 55 percent increase over spending 15 years ago. Seventy-two percent of those contributions have gone to Republicans.

Small farmers may be losing their voice, but so, too, are rural communities in general. Since 2010, 71 percent of Iowa counties have lost residents—almost all growth took place in urban areas.

State Sen. Joe Bolkcom, says “if this industrial model doesn’t change, we’re going to continue to see the depopulation of rural Iowa.”

This depopulation decreases Iowa’s political power in D.C. The state was one of a handful that lost congressional seats after the 2010 Census, dropping from five to four seats in the U.S. House of Representatives due to anemic population growth since 2000.

The congressional map is revisited and redrawn each decade after the population tally. The loss of a seat in 2010 left Iowa with its least representation in the House since 1850.

Rep. Baltimore says growth and consolidation in hog farming are economic issues and not something the government should interfere with.

“Walmart is successful, why? Economies of scale. And the same thing happens in rural communities and in the pork industry. What are we going to do, pass a law that you can’t farm more than 160 acres?

“The government shouldn’t be involved like that,” he adds.

Barbara Patterson, government relations director with the National Farmers Union, however, says “it’s hard to say that this is simply economics.”

“Many issues would be addressed if we tackled anti-trust concerns,” she says.

Enter the Matrix

Atop the wish list of people like Sue George is for local control of hog barn siting.

“Landfills, new homes, factories … land-use decision-making in Iowa is a local process. But with hogs, local elected officials have no voice,” Sen. Bolkcom says. He points to a recent attempt by counties to bolster the state’s environmental scorecard for hog farm siting, which was promptly shut down by state officials.

Critics say the industry influence has tied the hands of the Legislature in acting in any way seen contrary hog farming interests.

“Local control is preempted by state law,” says Adam Mason, state policy director with the nonprofit Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. “These small towns and counties need to be making these decisions.”

Former dairy herder, and former Republican, Iowa Sen. David Johnson agrees. Johnson, now an Independent, broke with his party last summer. That was due partially because he didn’t want to share a party with President Trump. But it also reflects his distaste with what he sees as a state Legislature in the pocket of Big Pork.

“We haven’t updated our livestock laws since 2002,” Johnson says. When Johnson started urging fellow Republicans to do so, he says he found himself shut out and marginalized.

Johnson, in a way, is wrong: There have been updates to livestock laws.

It’s just that they’ve all been gifts to industry.

The first came in 1995: A bill, pushed for and signed into law by then-Gov. Terry Branstad, who was recently appointed the U.S. Ambassador to China by the Trump administration. It took zoning authority over large corporate farms away from counties and local officials. Those decisions are now determined by state regulations.

The 1995 law also shifted the burden of proof in nuisance lawsuits onto the plaintiffs.

In Branstad’s five-decade career in Iowa politics he received almost $2 million in contributions from the agriculture industry.

In 2013, Iowa passed the nation’s first “ag-gag law,” making it a crime to falsify farm employment information or help someone get a job for an undercover sting operation. The bill was specifically in response to undercover video that raised animal rights concerns after it was shot a year prior at an Iowa egg farm and a hog operation.

Six more states have passed ag-gag laws since Iowa.

With little local control over hog farm siting, communities and local activists have fought back via lawsuits. This spring the governor signed into law a bill that limits damages in successful lawsuits against confinement farms.

“I don’t think anyone will ever succeed in a nuisance lawsuit again,” Sen. Johnson says.

State Republicans, however, see these as efforts to help the economy and the region —to help local folks build up businesses without getting their hands tied by outside groups.

“It would be a real challenge for me to adopt a viewpoint that we shouldn’t be encouraging large-scale livestock operations in rural Iowa. If not here, where the hell are you going to do it?” Baltimore says. “Agriculture—livestock and raising the feed for it—is the foundational building block of our state economy.”

Republicans, including Rep. Baltimore, defended the bill, dubbed Senate File 447, as an economic development bill to help farmers.

Local communities have one tool to fight Big Ag’s barns. The Master Matrix scoring system has been used since 2002 to protect communities and their air and water from proposed confinement farms of more than 2,500 hogs.

Hog farms in counties that use the Matrix have to go above and beyond state regulations to gain approval. Proposed farms have to outline on a scorecard how they plan to reduce negative impacts on the environment and the community.

But Sue George and other neighbors say the tool is badly broken. For starters, when farms apply, they need only a 50 percent or better to “pass” the Matrix. Even with that low bar, only 2.2 percent of applications for large hog confinement farms have been denied through the scorecard, according to the DNR.

Former state Rep. Mark Kuhn, currently a member of the Floyd County Board of Supervisors, was an architect of the Matrix. When we meet in early July, he tells me “it’s failed in many ways.”

Ken Hessenius, environmental program supervisor with the Iowa DNR, counters that the Matrix’s 97.8 percent approval rate is misleading: It doesn’t indicate a lax system.

“If they’re going to submit, they’re going to submit a passing application most of the time,” he says.

Earlier this year, 17 of Iowa’s 99 counties passed resolutions asking the state to strengthen the scorecard. In a loud meeting in late September filled with protests, the state’s Environmental Protection Commission voted unanimously to reject those suggestions. The pork industry said the changes—and an amended Matrix—would amount to a moratorium on new hog farms.

The Iowa Farm Bureau supports the current scorecard, says David Miller, the bureau’s research director. “As we expand we need to be doing it in a way that’s environmentally and socially responsible.”

The concept that “big is bad” is wrong, Baltimore says. “You can’t feed a world [raising] three hogs at a time.”

No slowing down

I’m on the phone with former union organizer Tom Willett, and he’s firing complaints rat-a-tat-tat from his home in Mason City about chicken and hog confinement operations.

“There’s this farm …”

“They didn’t care about us …”

“We took over the damn meeting …”

“Oh we’ll keep fighting…”

I can’t keep up.

Willett and others waged a very public fight against a proposed giant pork processing plant in Mason City last year and won when Prestage Farms pulled plans to set up the $240 million plant in Cerro Gordo County.

Two months prior Prestage had a 6-0 vote in their favor from city councilors; three councilors flipped after relentless opposition from Willett and like-minded folks.

But the victory in some ways was short lived.

Prestage, which raises hogs in about 30 counties in the state, just moved down the road. In March the company began construction on its plant in Wright County, an hour’s drive from their Cerro Gordo County site. “They’re all going to eventually land somewhere,” Willett says.

Other small Midwest towns have turned away large processing plants in recent years—including Nickerson, Nebraska, (a big chicken processor), Scottsbluff, Nebraska, (a beef-packing plant)—but the demand for meat necessitates processing.

Pork processing capacity is set to increase about 10 percent over the next two years with an estimated five new processors opening—two in Iowa (Prestage and another in Sioux City), one in Coldwater, Michigan, and two smaller ones in Missouri and Minnesota.

Ron Plain, an agricultural economist from the University of Missouri, says hog production growth in the U.S. is rising about 1 percent to 3 percent every year.

The USDA estimates that U.S. pork production will be equal to or greater than that of beef in the next decade. Pork production, estimated at 25 billion pounds in 2017—should increase 10 percent over the next decade.

Domestic sales are up 20 percent over the past six years, according to market research.

But the big prize is overseas. Total U.S. pork exports to Hong Kong and China jumped 222 percent from 2007. Today, it is a billion dollar business. Total export value—and metric tons of pork shipped— to all countries from the U.S. almost doubled over this 10-year span: 2.3 million metric tons of pork a year, valued at $5.9 billion.

It’s a trend that means even more big companies—and outside influencers—will be seeking a say in what happens in small-town Iowa.

Iowa had just 33 construction permits for large animal feeding operations in 2001. That shot up to 264 in 2005, and, since then, more than 1,990 more permits have been issued.

It’s not clear where the breaking point lies. There are roughly 11,000 animal confinement operations in Iowa, and a presentation earlier this year from the state DNR reported the land could support 45,000. Distance restrictions wouldn’t allow that many, but that thinking puts a scare in Petersen. “Could you imagine?” he asks. “We’re certainly moving in that direction.”

And experts say there is no slowing down.

“The demand for bacon keeps going up. I don’t see a bubble, I see steady growth,” says Miller of the Farm Bureau.

New friends and fights

Sue George walks me out of her farmhouse. She has to prepare for the community meeting she’ll host at her house that night. The fight against the hog barns, she notes, has brought people together—to fight for clean water and property rights.

“We’re all good friends now,” she says. “We have mechanics, veterans, farmers, Republicans, Democrats, a feisty grandma … all kinds of folks.”

She says the meetings help—for a bit. “You get all excited meeting with neighbors, thinking you can fight this.

“But it often feels like you can’t.”

Editor’s note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN’s investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms.