AgWeb: Cover Crops And Cattle Are Cash

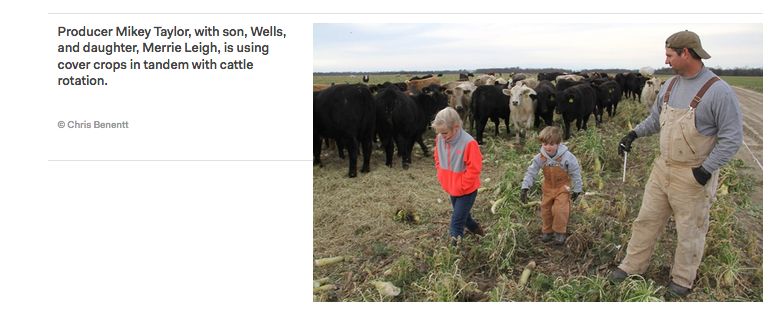

Farm girl Merrie Leigh Taylor, stands in a Long Lake Plantation paddy planted with cereal rye and tillage radish.

by Chris Bennett | January 2, 2018

Mikey Taylor felt like a slave to soil testing.

In a battle against hardened ground and poor soil quality on some of his east Arkansas farmland, Taylor turned to soil testing and NPK. But instead of answers, he found contradiction. Representative soil samples sent to multiple labs across the United States produced different results – separate and entirely unequal. Salvation in a soil sample? Not for Taylor.

He was chasing a remedy that put him on the trail of a cover crop solution. Initially planting cover crops solely for erosion protection, Taylor transitioned to soil health covers, and recently to grazing covers in tandem with cattle rotation. On Taylor’s ground in Phillips County, Ark., livestock are the vehicle to building high-potential soils.

Taylor, 38, farms with his father Mike at Long Lake Plantation — a family operation dating to 1938. Taylor’s standard crop roster includes corn, cotton, grain sorghum, peanuts and soybeans. In 2010, he got an unexpected soil surprise after planting corn and soybeans on 250 acres of cleared, high-ground hardwood in three blocks. The dryland corn yielded 200-plus bu. per acre and the dryland soybeans tallied 80-plus bu. per acre. Directly across the road on old farming ground, the yields weren’t hitting such high rates.

For more on soil health, see Heart of Delta Hides Visionary Farmer

The first producers to clear ground at Long Lake followed the contours of soil types. The high ground never flooded and carried a presumption of inferiority. When Taylor first cleared the 250 acres, he decided to replant in hardwood and let his children reap the benefits. But safe from flooding, the high ground drove his decision to plant corn and soybeans. When the yields jumped, he strongly suspected the formerly wooded acreage was reaping the benefits of nature’s cover crop.

Taylor had already put ground in cover crops for several years, initially planting cereal rye to keep soil down during winter rains and spring winds. His cover crop usage progressed toward building organic matter and maintaining soil health. In 2014, Taylor’s growing interest in cover benefits pushed him to seek out Doug Peterson, a soil health specialist for Iowa and Missouri, with the National Resources Conservation Service. “I came home from the meeting with Doug and sat down with a plan to implement a cattle and cover crop to soybean system,” Taylor says.

Grazing cover crops with cattle is an old practice. Cows faded out of the row crop picture, but with the integration of cover crops, cattle are returning. “You’re essentially turning the cover crops into a cash crop,” Peterson explains. “In this system, cover crops offer soil health benefits and manure that add a financial incentive to row crops, and they also turn into cash as livestock fodder.”

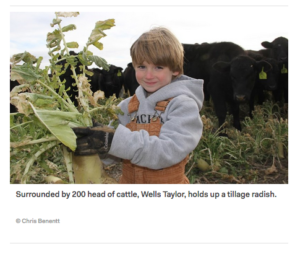

On June 16, 2015, the day after he began cutting wheat, Taylor planted a 13-way blend cover of legumes and grasses into the stubble. The cover combination grew phenomenally fast, and 45 days later it was head-high and ready for cattle rotation. Taylor runs 100-head of cattle on a single acre for 24 hours and moves the herd each day to a new acre. Once grazed, an acre is typically ready for rotation again in 40 days. “Keeping the cows on a single acre is key and spreads the manure evenly,” Taylor explains. “Turn 100 head loose on 150 acres and they’ll graze in patches. The ground will get uneven manure distribution.”

On a solitary acre, cattle eat in a concentrated pattern. The result is a 150-acre checkerboard field. Taylor moves cattle acre by acre until October, and then moves them to the opposite side of Long Lake on acreage with winter cover crops planted behind grain sorghum. On the land the herd has exited, Taylor plants cereal rye as a winter cover. He kills the cereal rye in spring and plants soybeans into the mat in April. The system constantly shifts ground over multiple years.

On a solitary acre, cattle eat in a concentrated pattern. The result is a 150-acre checkerboard field. Taylor moves cattle acre by acre until October, and then moves them to the opposite side of Long Lake on acreage with winter cover crops planted behind grain sorghum. On the land the herd has exited, Taylor plants cereal rye as a winter cover. He kills the cereal rye in spring and plants soybeans into the mat in April. The system constantly shifts ground over multiple years.

On fresh ground, the cattle transition from a warm season summer cover to a cool season winter cover. Because the cycle is bigger and the grass doesn’t last as long, Taylor breaks the system into 15-acre paddies over three days. “Some of it may be my laziness, but you don’t have to move them each day,” he says.

On its face, the continuous effort to move fence to accommodate cattle rotation is a logistical nightmare. Not so, explains Taylor. The cows anticipate fresh grass and move themselves to the gate, waiting for the next pasture. He runs a high-tensile electric fence around the block perimeter. The acreage cutoffs are done with temporary, highly visible polytape fencing on 660’ spools. “The white polytape basically spins off a big fishing reel and connects to posts 50’ apart. Total labor takes two men a couple of hours each day,” Taylor says.

Once infrastructure and water are in place, labor is time consistent regardless of herd size, explains Peterson, who maintains a grazing operation in northern Missouri. “Most of this ground hasn’t had a livestock presence in decades, so water and fence systems have to be put in. But fencing technology has jumped dramatically and polywire’s braided conductivity and easy visibility makes it a great, simple product to contain livestock.”

In the off-season, the cover crop and cattle system increases organic matter and the potential for stronger row crops. The soil builds nutrients instead of lying idle and dormant. In Taylor’s case, crop fields have been exposed to years of tillage, resulting in reduced biological activity. But packed with biological organisms, cattle manure serves as an antidote, particularly with the consistent and even spread provided by the fencing system. In tandem with manure, cattle saliva releases biological activity into the ground as cows feed, according to Peterson. “This system is beneficial to the soil, but also to the animals. Giving them a fresh plate of grass every day ensures they’re at the highest level of health. Some farmers move them twice daily, enhancing health even more. Taken over the course of a season, the herd is drastically improved.”

For more on Taylor, see Field of Greens: Cover Crops Turn Into Picker Blessing

Prior to cattle rotation, Taylor was planting cool season covers at roughly $20 per acre. “We added to the quality and it’s now costing about $35-$40 for a winter-graze mix,” he says. For his warm season covers, Taylor’s seed company devised a mix specifically for Long Lake’s rotation. During summer, Taylor waters the warm season covers with pivots and polypipe. In fall 2015, he watered his winter cover with pivots during an eight-week drought.

Livestock is a new facet of the Long Lake operation, and Taylor has learned on his feet. He buys cattle from Clayton Zeerschke, Batesville, Miss., who purchases the cows at auction and conditions them, before delivery to Taylor 38 to 45 days later. “I couldn’t manage my cattle without Clayton. I’m blessed with tremendous help. I’m also blessed to farm and involve my children in farming on a daily basis.”

Taylor’s cover journey has moved from erosion control and soil health to cash crop. “Livestock are the ultimate means to building high-potential soils,” he adds. “I treat my covers like row crops because my cows depend on them and so does my ground.”