Washington Post: ‘I don’t know how we’re going to survive this.’ Some once-loyal farmers begin to doubt Trump.

by Annie Gowen | June 21, 2019

ORIENT, S.D. — The sky had finally cleared after weeks of record-setting rain, and now farmer Ray Martinmaas was facing a time crunch.

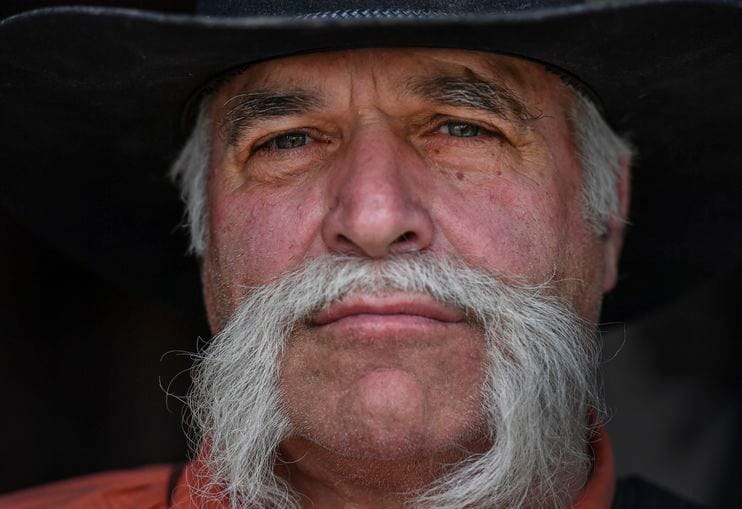

He was out in his white Ford F-150 Raptor pickup, searching his family’s 15,000 acres for areas dry enough to plant corn in time to mature by fall harvest, passing places where new bodies of ruinous water glittered. He spotted his neighbor Mark Cotton, another farmer, and slowed his truck to talk.

“Still too wet?” Martinmaas asked.

“We’re spinning our wheels,” Cotton replied. “This trade thing is going to kill us.”

More than 1,000 miles away in Washington, another deadline was looming. To avoid a potential trade war with Mexico, negotiators were rushing to hammer out a deal to stem the wave of migrants flowing through the country to the U.S. border. Without an agreement by the coming Monday, President Trump said he would implement punishing new tariffs on Mexico, dealing another blow to farmers like those here in Orient, S.D., where residents were already reeling from the trade war with China and months of bad weather. ADVERTISING

Like farmers around the country, they were faced with gut-wrenching choices: Plant their corn in muddy fields or file an insurance claim? How much would they receive from the $14.5 billion of aid that Trump promised in May to offset their losses from China’s tariffs, and what crops would they have to plant to receive it?

Some rural residents are growing increasingly frustrated with the ongoing trade feuds and wonder how long Trump will call upon farmers to make sacrifices as the country’s “patriots.”

“People are starting to say, ‘I don’t know how we’re going to survive this,’ ” said Martinmaas, who voted for Trump in 2016, but says he’s open to a Democrat like Montana Gov. Steve Bullock this time. “You know, we’re the ones taking the brunt of it in all these negotiations, so they need to be kind of helping us out right now.”

Martinmaas, whose family homesteaded this land in 1888, said his farm operation lost more than $700,000 last year. He’s had to put a moratorium on buying new equipment, and he’s stuck with grain bins full of soybeans, because China isn’t buying. Other farmers can’t pay their bills for the hay and grain they bought from him.

Martinmaas, 69, says he’s skeptical that Trump’s aid package will help, given the uncertainty about how much individual farmers will receive and who will qualify.

Trump’s 2016 victory hung largely on support from rural and small-town Americans like Martinmaas. His approval rating with them remains strong — 57 percent, far higher than the 39 percent of Americans overall, according to a Washington Post-ABC News poll in late April.

But a survey of farmers released this month by Purdue University’s Center for Commercial Agriculture shows rising pessimism, with only 20 percent saying they believe the trade war with China will be resolved by July 1, down from 45 percent in March.

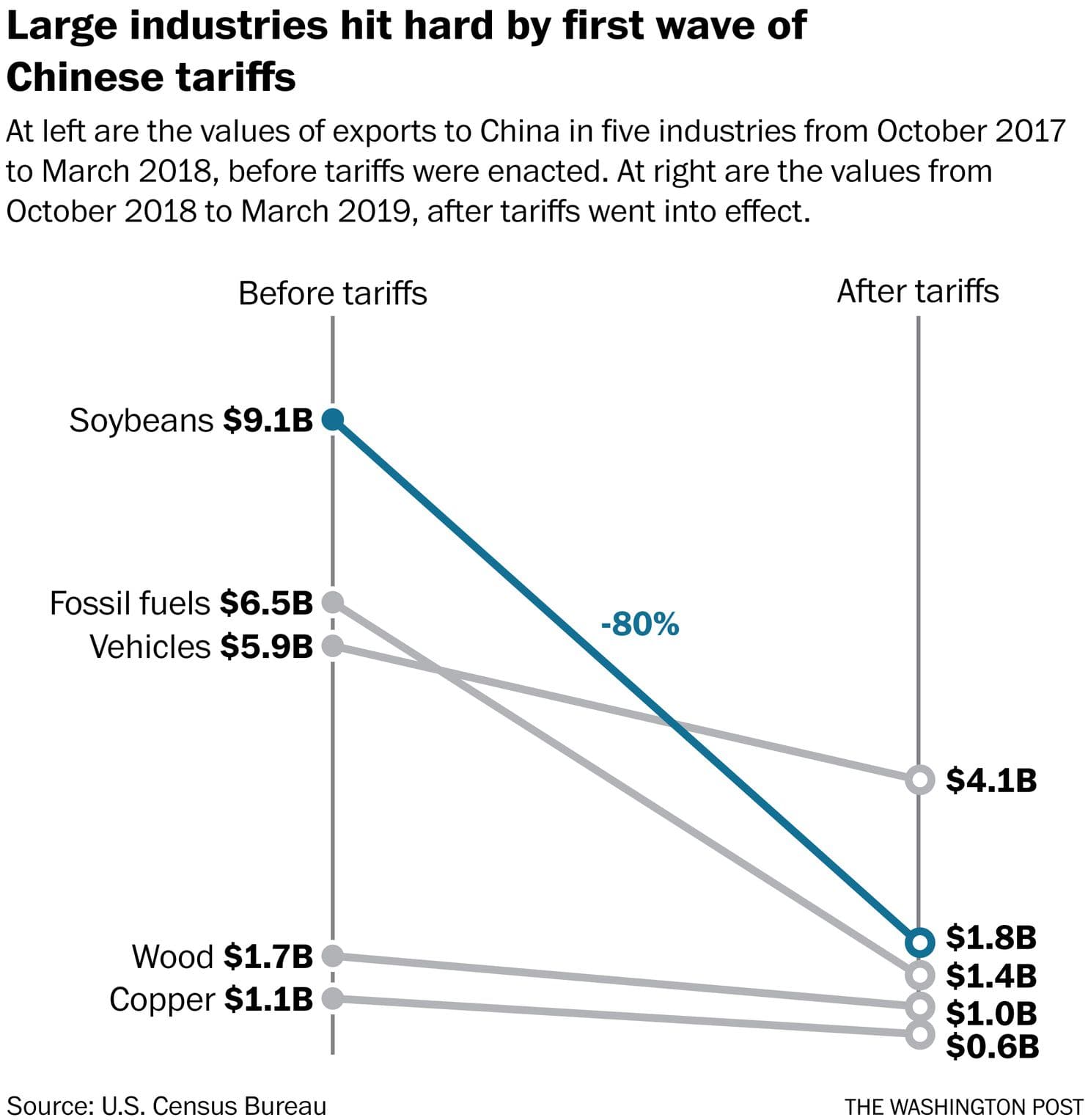

But in tiny Orient — population 63 — farmers are beginning to voice disillusionment and frustration. More than a dozen farmers did not have their operating loans renewed for the coming year, according to a local lender, with at least one farmer losing it all and a land auction planned for the courthouse steps later this month. Agriculture exports from the state to China — a big soybean buyer — fell 40 percent in the state last year, part of a $10 billion loss nationally, according to an American Farm Bureau Federation analysis.

The bailout package “is like putting a Band-Aid on a bleeding artery,” said Jennifer Poindexter-Runge, a local veterinarian, who expects her family farm income to drop by 25 percent this year. “It’s not going to save anybody.”

‘Put up or get out’

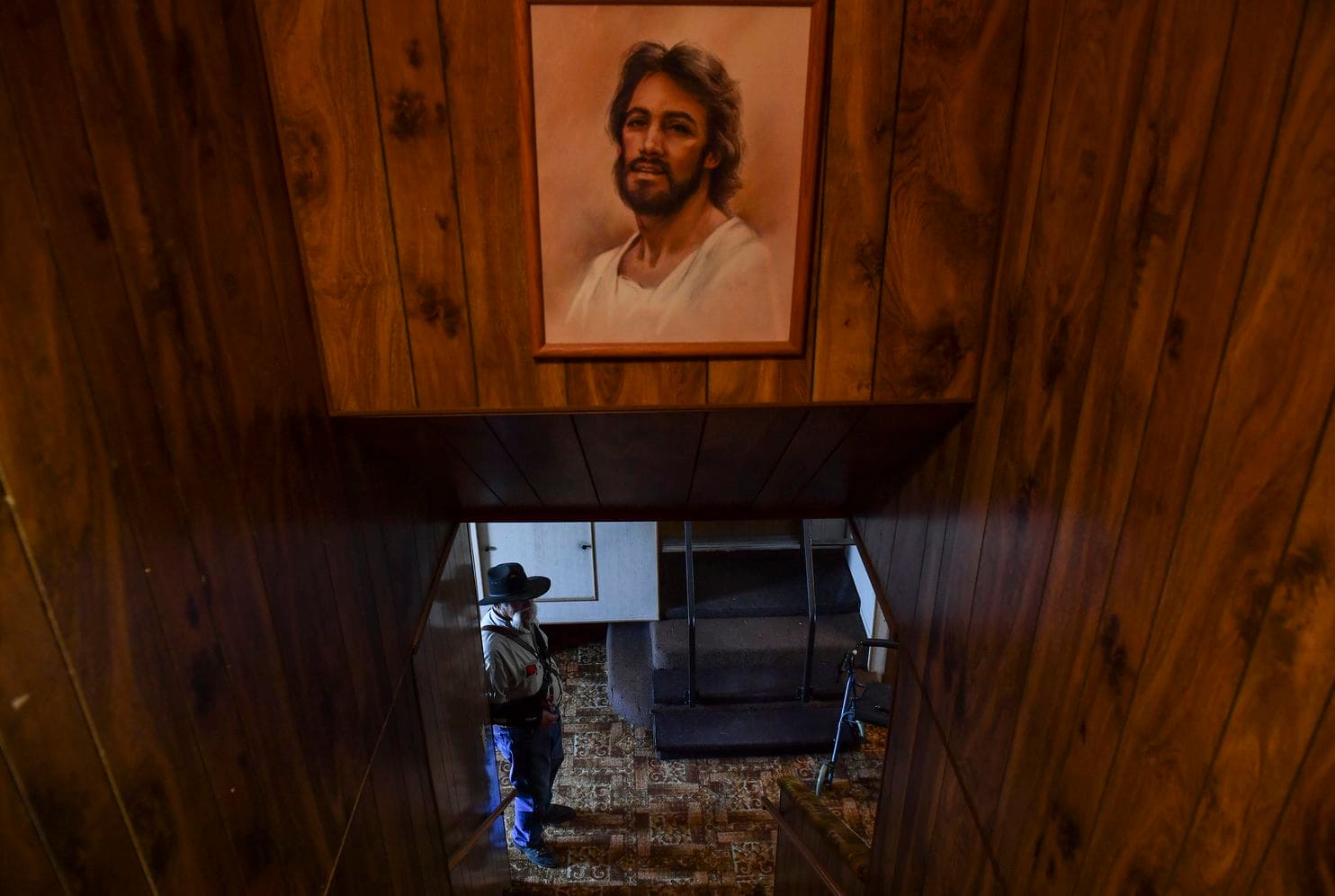

Martinmaas runs his farm operation — including Angus beef cattle, corn, soybeans, sunflowers and hogs — with his three brothers. He was born and raised in Orient, in a tiny house with no electricity or running water, one of 12 children of conservative Catholic parents. Now he lives with his wife, Becky Martinmaas, in a cozy house decorated in a lodge theme, with a gun room, workshop, horse barn, skinning shed and a salt-lick pallet out front, which Becky hand-painted in the colors of the American flag and the words “Let Freedom Ring.”

Married 31 years, they share a commitment to hard work and family, a love of sport shooting and hunting, and a distaste for coastal elites.

“I always say the West Coast and East Coast can each be a country and the rest of us will be just fine,” Martinmaas said from his kitchen table one recent Sunday, as Becky made butter biscuits.

“But they’d starve!” she said.

“Here in flyover country, we have everything we need — food, oil,” Martinmaas said.

“Except voters,” his wife responds.

Becky doesn’t share Martinmaas’s growing disillusionment with Trump. First, it was his abusive tweets — “I wasn’t raised that way,” Martinmaas says. Now, it seemed that Trump, whom he once embraced as the street-fighting outsider that farmers need, isn’t going to deliver on his promises to his rural supporters.

“He said he’s going to straighten these tariffs out, didn’t he? Well it’s put up or get out, you know?” he said in late May. “If he wants to get reelected he’s going to have to take care of farmers, and we still have to end the trade wars, and by ending them I mean in our favor more so than less so.”

As Trump’s June 10 deadline for Mexico’s tariffs approached, news of the trade negotiations in Washington played on the television at the local Cenex gas station, in tractor cab radios and in homes, on Fox News and CNN — what locals call the “Chicken Noodle Network.”

In this part of South Dakota, Trump won by a large margin, nearly 77 percent of the vote. Many still say they support him and that these trade disputes will one day lead to more open markets for their crops.

Among them is Martinmaas’s brother Randy, 68, a follower of conservative commentator Rush Limbaugh, who criticizes Republicans for doubting Trump’s tariff-threat tactics.

“Trump’s going to do right by us, more than the other people in Washington, and get this straightened out,” he said.

The brothers were at Randy’s farm, trying to fix a tractor stalled because of a broken exhaust sensor. They were risking thousands of dollars a day with this delay. So Martinmaas had to jump into his truck for the 35-mile ride to the nearest John Deere dealership for a replacement part.

“This is what makes me so mad. We’re already late planting corn and now one little thing goes wrong and we can’t move because the government says it’s mandatory to have this part on,” he fumed. To Martinmaas, the federal emissions controls on tractors were just one more example of the government meddling unnecessarily in his business, like restrictions on killing wolves that threaten his cattle, or health-care costs that he says rose after the Affordable Care Act.

He gunned the engine to 80 mph on the gravel road, the Raptor’s wheels spitting rocks, then up to 100 mph when he hit the open road.

When it rains

The tractor was back up and running by evening, when Trump tweeted that he had reached a deal with Mexico in response to the country’s pledge to take “strong measures” to curb the influx of Central American migrants, averting the tariff threat.

Randy saw this as a win; Martinmaas isn’t so sure. He doesn’t like the idea of farmers being used as pawns.

“We want the border secured, but there might be other ways to do it rather than using the farmers as a stick to beat Mexico over the head,” he said. “Farm states elected him, and everyone around here is still giving him the benefit of the doubt. But if, in a year and a half, we’re still in the same boat, he’s not getting elected.”

The next morning, dark clouds appeared on the horizon and thunder rumbled from a distance. Rain first appeared as a delicate tracing of black against the iron-gray clouds, then a full-blown storm came “boiling across the prairie,” as Becky described it.

Randy — who had planted until he got stuck in the mud at 2:30 a.m. — was already back in the field, swinging the corn planter in wide circles around the pools of standing water. He was thinking that they had it bad this year, but not quite as bad as his homesteading German ancestors, who survived their first winter in South Dakota in a mud dugout.

About that time came another Trump tweet, in all caps: “MEXICO HAS AGREED TO IMMEDIATELY BEGIN BUYING LARGE QUANTITIES OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCT FROM OUR GREAT PATRIOT FARMERS!”

By midafternoon, the rain started coming down in torrents, a storm that would ultimately deliver about a half-inch of rain. They probably would have to wrap up their corn planting for the year, Martinmaas said, and go with less lucrative crops like soybeans and sunflowers with later plant dates.

“We sure didn’t need that,” he said.

He was looking up at the gunmetal sky, and a deluge that seemed never-ending.