Washington Post: Advocates hoped census would find diversity in agriculture. It found old white people.

by Laura Reiley, Andrew Van Dam | April 13, 2019

The Agriculture Department’s newly released 2017 Census of Agriculture is 820 pages of graphs, tables and puzzling shifts (half as many llamas but the number of minks rose toward 1 million). This census comes out every five years and is the most accurate and detailed look at America’s vast, complicated and shrinking agricultural sector.

Its data is used by those who serve farmers and rural communities — but it also shows who farms and what challenges they face. Those challenges, farmers and their advocates say, are legion.

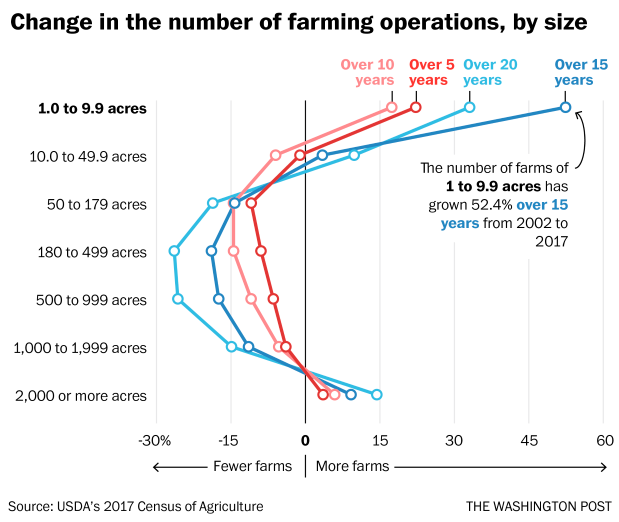

A central theme of this census appears to be a hollowing out of the middle: All categories of midsize farms declined over the past five years. Farmer’s ages skewed older, leaving questions about what happens when they age out.

“We’re not going to suddenly attract 40-year-olds,” said Jeff Tripician, president of Perdue Premium Meat, the parent company of beef, lamb and pork producer Niman Ranch. “We have seen a 30-year decline in almost every single metric. They’re all bad. The number of jobs lost, the average net income down 45 percent since 2013. There’s no news here. It’s an acceleration of bad. What have we done to fix this?”

It doesn’t all live up to Tripician’s apocalyptic vision, though there’s cause for concern.

The number of farm operations dropped 3.2 percent to 2.04 million. Total acreage farmed nationwide dropped 1.6 percent, while the average farm size increased by the same percentage, to 441 acres.

Industry consolidation continued. The number of dairy farms dropped 15 percent from 2012, but the number of milk cows rose. The National Agricultural Statistics Service, which compiles the census, indicates that just 105,453 farms produced 75 percent of all sales in 2017, down from 119,908 in 2012.

Almost as a rebuttal to this get-big-or-get-out pattern, this census revealed a surge in the number of farms below nine acres. The number of pint-size pastoralist operations rose about 22 percent from 2012 to 2017, reaching about 273,000 farms.

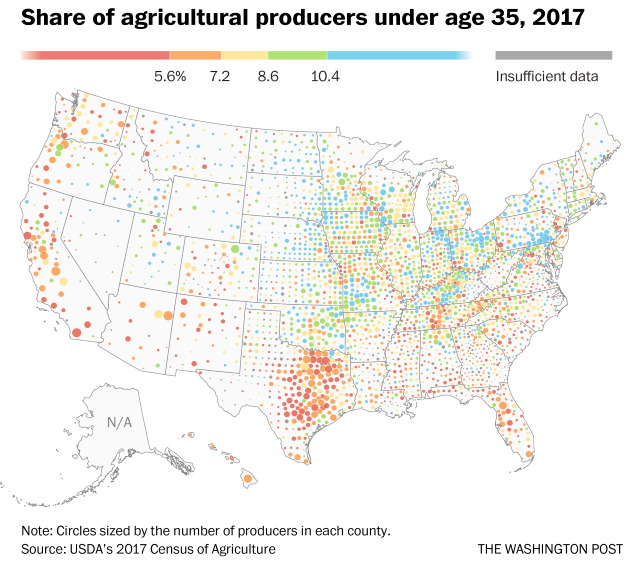

The numbers aren’t strictly comparable due to a methodology change, but the number of farmers and ranchers below the age of 35 is also up, rising 11 percent to about 285,000. They’re thoroughly outnumbered by the 396,000 producers age 75 and older, however.

Beginning producers (those with experience in farming of 10 years or fewer) make up 27 percent.

Still, the average age of U.S. farm producers in 2017 was 57.5 years, creeping up from 56.3 years in 2012.

“As farmers age out and retire,” Sophie Ackoff of the National Young Farmers Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for young farmers, “we’re not adding enough new farmers to make up for it. That’s why we need to focus on technical service and loans and grant programs. We need younger farmers to succeed because there aren’t enough of them.”

But there were pockets of real growth in this census, which was originally scheduled for February but postponed by the partial government shutdown early in the year. The ranks of organic farmers swelled from about 14,000 to about 18,000, and total sales of domestic organic product more than doubled. An average organic farm sold about $401,000 of goods in 2017, up from $218,000 five years earlier.

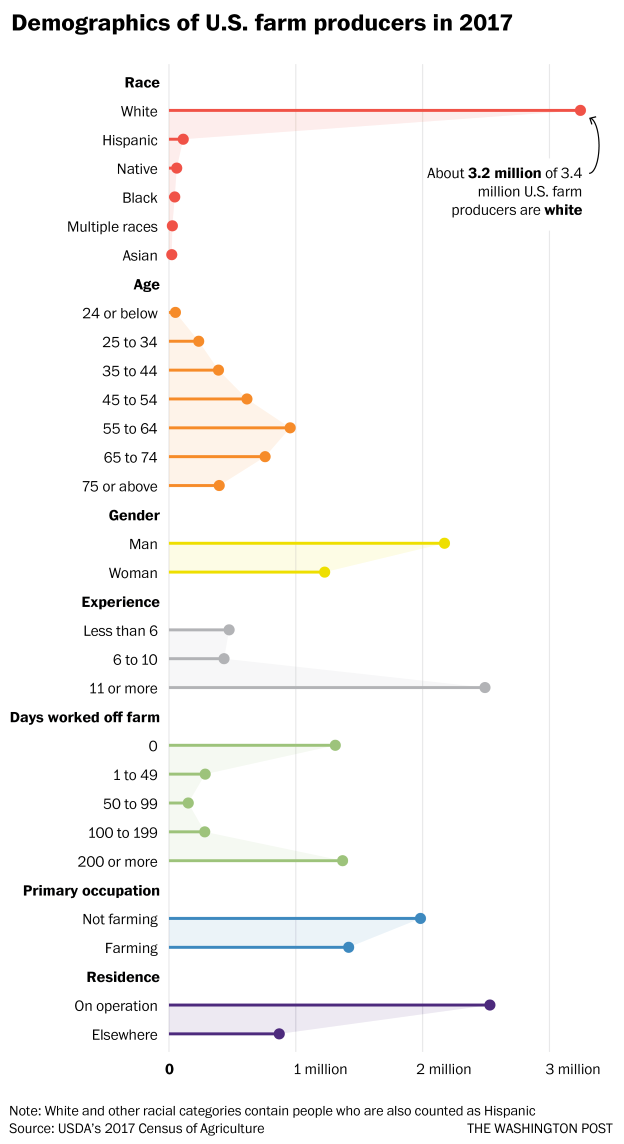

While the number of male producers declined 1.7 percent, the number of female producers increased nearly 27 percent to about 1.23 million. This may reflect changes in how farmers were counted this go-round, said Erin Foster West, federal policy director for National Young Farmers Coalition.

The census used to ask for data on three operators on a farm as well the principal operator. They’ve done away with the principal operator question — perhaps a vestige of a patriarchal hierarchy where Grandpa or Dad was in charge but everyone in the family helped — and count up to four producers on each farm.

“This meant that, previously, it may not have included young farmers and female partners. They might not have made it into the census, but we think they’ve always been there,” Foster West says.

But even this more accurate count shows farmers are still overwhelmingly white. Ninety-five percent of producers are white, 3.3 percent are Hispanic, and 1.7 percent are Native American or Native Alaskan. Other ethnic groups include African Americans (1.3 percent), Asians (0.6 percent), Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders (0.1 percent) and “more than one race” (0.8 percent).

Regardless of race, only two out of every five American farm producers (1.42 million) list farming as their primary job. Almost as many, 1.37 million, spend 200 days or more each year working outside of the farm.

Ackoff points to young and new farmers whose strategy is cooperative or multifarmer-owned farms. Multiple owners mean profits are spread thinner, often necessitating an outside income source.

“Friends have decided it’s easier to farm together,” she says. “It’s a response to high labor costs. You train people and they leave. Having another co-farm owner is a much more stable labor source for your farm.”

But with labor and input costs up and the total market value of products sold down, this census offers many reasons American farmers are hedging their bets with a day job.