The Conversation: EU’s antitrust ‘war’ on Google and Facebook uses abandoned American playbook

European Union Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager has followed an antitrust enforcement strategy pioneered in the U.S. AP Photo/Virginia Mayo

by Ramsi Woodcock | July 13, 2017 10.44pm EDT

The casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that European antitrust regulators have declared war on American tech giants.

On June 27, the European Union imposed a €2.4 billion (US$2.75 billion) fine on Google for giving favorable treatment in its search engine results to its own comparison shopping service. And Germany’s antitrust enforcer is investigating Facebook for asking users to sign away control over personal information.

In contrast, American antitrust enforcers have shown little interest in these companies. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) did open an investigation into whether Google has a search bias, but closed it in 2013, despite recognizing that it “may have had the effect of harming individual competitors.”

Anti-Americanism, however, does not explain these starkly different approaches. Europe targets homegrown companies with the same ferocity. Last summer, for example, the EU fined a cartel of European truck-makers even more than it did Google.

Instead, the divergence is explained by America’s abandonment in the 1980s of the theory that competition promotes innovation, which is still embraced by Europe today. America now seems to operate under the theory that competition threatens innovation by denying companies that develop a superior product the rewards of monopoly.

My research suggests that embrace of this new theory has led to under-enforcement of America’s antitrust laws, which may in turn have actually held back innovation.

Betting on competition

The mission of antitrust law, first articulated by the framers of the Sherman Act in 1890, is to ensure that markets contain large numbers of equally matched competitors. That’s why Europe calls its own antitrust rules “competition law.”

The Sherman Act implemented this goal by prohibiting two things: “restraint of trade,” such as price fixing, and monopolization, the attempt of a powerful company to keep competitors out of its markets. European competition laws have a similar bipartite structure.

The EU case against Google falls under the second category, monopolization, or as Europeans dub it “abuse of dominance.”

One of the most important and difficult areas of the law of monopolization involves infrastructure, which can be anything from the roads that crisscross America to the engineering standards that mobile phones use to communicate. Great innovations, such as Google’s search engine, often become the infrastructure that the next generation of competitors need to access in order to create their own, innovative products. But the infrastructure owner will often shut those competitors out, to maximize profits.

The goal of antitrust law would seem to require that its enforcers – the Department of Justice and the FTC in the U.S. – sue to force owners to share their infrastructure on reasonable terms with competitors.

Skeptics emerge

But in the 1960s, skeptics – particularly antitrust economists and lawyers associated with the University of Chicago and led by Robert Bork – started to argue that forcing a business to share its infrastructure on an equal basis with competitors reduces the rewards a company can expect to generate from innovation, potentially discouraging technological progress.

If Google cannot earn monopoly profits on product search and sponsored links, will it stop investing in improving its search engine?

Getting the answer right is hugely important. Access to infrastructure may well have triggered the Industrial Revolution. A recent study shows that the abolition of serfdom in Russia in 1861 – which broke up the monopoly of feudal lords over a very important type of infrastructure, land – greatly increased the growth of the Russian economy. The authors concluded that Western Europe’s abolition of serfdom at least a century earlier probably explains its subsequent economic dominance.

Until the 1980s, American antitrust enforcers followed this example by breaking up “feudal estates” when they got too big. In 1912, for instance, the Justice Department won a case that forced the owners of the only two railroad bridges crossing the Mississippi river at St. Louis – which connected numerous eastern and western railroad systems – to allow access to competing companies.

The bridges were a superior product, relative to railroad ferries, and the sharing requirement no doubt reduced the owners’ profits. But the Justice Department was willing to bet that intervention would not chill incentives to innovate. America has done OK since.

The Justice Department made the same bet when it filed its last successful monopolization case in 1974, making AT&T give up the local telephone networks that once ran copper wires into most homes in America. That allowed an innovative competitor, MCI, to use those wires to connect home and office telephones to the company’s pioneering microwave and satellite transmission systems, halving long distance calling rates by 1990.

The last major monopolization case was filed in 1998 against Bill Gates’ Microsoft and its then ubiquitous operating system Windows. AP Photo/Paul Sakuma

Betting against competition

The view of the Chicago skeptics who opposed enforcement grew in power during the 1970s, reaching a tipping point in 1981 with the election of Ronald Reagan, who appointed its advocates to federal judgeships and leadership roles in the enforcement agencies. That view has proven resilient to changes in administration ever since.

The courts implemented the Chicago view by embracing a rule, known optimistically as the “rule of reason,” that enforcement of antitrust law is warranted only if there is no danger of chilling innovation. As the Supreme Court put it, intervention should take place only after “elaborate study.”

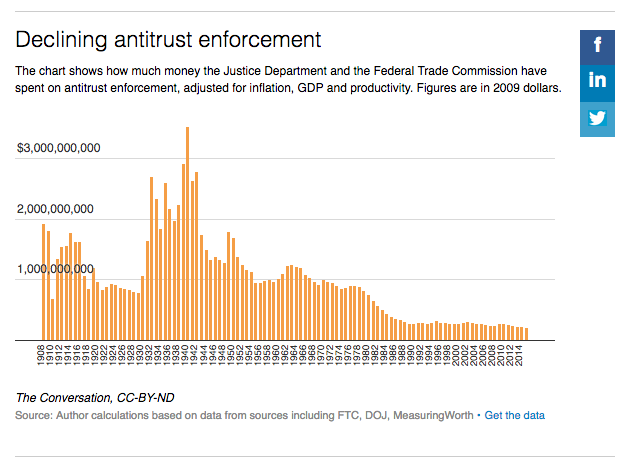

I argue in a recent paper that when enforcer budgets are limited, the rule of reason is just a polite way of partially repealing the antitrust laws, because the rule makes infrastructure cases, among others, too expensive for enforcers to litigate. And enforcement budgets are limited. Although budgets have increased in real terms since the 1970s, they have declined relative to the size of economy.

Antitrust enforcement has, in fact, suffered. Apart from the Microsoft case 20 years ago, in which the goal of breaking up the company wasn’t achieved, no other major monopolization cases have been filed since AT&T in 1974.

And even when cases are brought, usually by private individuals, the rule of reason has proven a virtually insurmountable obstacle to success.

Has all this at least led to an uptick in innovation? You might think that the answer is “yes,” given that Google and Facebook were both launched in the U.S. in recent years.

But both – as well as their incredible innovations – are the products not of monopoly but of competition. Google won the search wars by creating algorithms that beat those of rivals, including AltaVista and Yahoo. Facebook innovated by improving on the social network concept that erstwhile rival MySpace helped create. Both companies flourished thanks to equal access to the internet – in other words, net neutrality.

Measures of innovation for the economy as a whole, rather than individual success stories, provide a more reliable, and less encouraging, picture. The talk of the economics profession these days is the current combination of soaring corporate profits with the absence of an accompanying uptick in one measure of economy-wide expenditure on innovation – business investment.

This outcome is exactly what you’d expect in an economy of large companies that generate profits from their monopoly positions, rather than by offering better products.

The road not taken

Europe has not followed this path.

In the 1950s and ‘60’s, when the foundations for current European antitrust law were being laid, American enforcers still believed that competition promotes innovation. The American emphasis on protecting upstarts resonated with a continent still recovering from Nazism, which used state-sponsored monopolies to maintain control. The EU case against Google is firmly in that tradition, as is the investigation of Facebook, which dominates another new economy infrastructure, social media.

Although the European enforcement actions will only directly benefit Europeans, they are a reminder to Americans of the road not taken.