PRIME Act Would Steer Meat Processing in the Right Direction

PRIME Act Would Steer Meat Processing in the Right Direction

A great new bi-partisan House bill would wrest control over intrastate meat slaughter from the USDA.

Baylen Linnekin | August 1, 2015

Late last week, Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) introduced a bill that would dramatically re-shape the way many animals are slaughtered for food in this country. The PRIME Act, which has several co-sponsors, including Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) and Reps. Justin Amash (R-Mich.), John Garamendi (D-Calif.), Scott Garrett (R-N.J.), Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), and Jared Polis (D-Colo.), would give states the option of setting their own rules for processing meat that’s sold inside state borders. That’s a power Congress took from the states and handed to the USDA in 1967.

This is an issue that interests—and concerns—me greatly. I moderated a panel on reducing legal barriers to entry for livestock farmers and ranchers at Harvard Law School last year. As I also wrote here last year, in the wake of a food-safety scandal that forced the USDA to (rightly) close a California slaughterhouse, local slaughter options are few and far between for many farmers around the country.

The lack of USDA-approved processing plants forces farmers and ranchers of all sizes and types to funnel their cattle to one of a limited number of typically far-off USDA slaughterhouses. That regulatory stranglehold on meat processing has real-world consequences, because only meat processed at these USDA-approved slaughterhouses may be sold commercially in the United States. What’s more, when a food-safety violation is found at one of these facilities, the USDA can order meat from all sources—regardless of its safety—to be destroyed. That was the case in the California example I discussed in my column.

As I also noted, a growing demand across the country for increased food choices, such as local, grass-fed beef, is being suppressed by the dearth of USDA-approved slaughterhouses. While it’s true that meat currently may be processed at “custom” facilities that are not certified by the USDA, the sale of such meat is severely restricted.

So just what is the PRIME Act, and why do we need it? As Rep. Massie told me by phone this week, the bill is intended “to enable local farmers to sell their products to local consumers without all of the red tape and expense [posed by] the federal government.”

In place of that red tape, the simply worded, three-page PRIME Act would let states set their own standards.

Rep. Massie, who with his family raises cattle on his Kentucky farm, knows the impact of USDA processing rules better than most.

“I’m a beef farmer myself,” he tells me, “and when I take my animals to be processed, I drive past a custom facility three miles from my house and travel three hours to a USDA facility.” This is common. In talking with farmers and ranchers, it’s a story I hear time and again.

As Rep. Massie explains, the facility certification process is expensive and challenging. Something as trivial as the diameter of a drainpipe in a concrete floor can make or break a certification application.

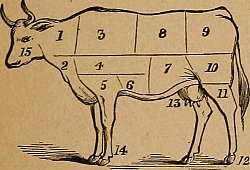

“The current custom-slaughter system doesn’t help farmers to succeed,” Rep. Massie says. As he tells me, the current system that allows farmers to sell beef that wasn’t processed at a USDA-certified facilities also creates several senseless hurdles for the small farmer and his buyers. First, Rep. Massie notes, the rules force farmers to sell off ownership shares in a live cow, rather than, say, selling the steaks and roasts from the cow. Typically, that means a consumer must buy a share of at least 100 pounds, even if they just want to buy a pound of hamburger. It also means consumers can’t choose to buy, for example, only steaks or only roasts. They’re bound to buy steaks and roasts, liver and ground beef. And they almost certainly are forced to buy the meat frozen, rather than fresh, as—speaking from experience—it’s near impossible to eat 100 pounds of fresh meat in a sitting.

This, Rep. Massie tells me, is “how the rules keep consumers from buying what they want from farmers.”

Not surprisingly, the PRIME Act is resonating with farmers and advocates across the country.

One person who sees the possibilities of the PRIME Act is Wyoming State Rep. Tyler Lindholm (R). I interviewed Rep. Lindholm earlier this year after he helped secure passage of Wyoming’s groundbreaking Food Freedom Act, which deregulated many food transactions on farms in the state, save those pertaining to most meat, as that still falls under the USDA’s authority.

“Needless to say, there’s quite a few of us in Wyoming that will be watching this bill closely and doing as much as we can to ensure its passage,” Rep. Lindholm told me by email this week.

“Not only will this legislation fill in the gaps for Wyoming’s Food Freedom Act,” he says, referring to the continuing involvement of the USDA in intrastate meat processing, “but it will open the door to opportunities for [a]griculture producers that they haven’t had in decades.”

“Congress gave USDA jurisdiction over intrastate meat commerce in 1967 and the results have been a disaster,” says Pete Kennedy of the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund, in an email to me this week. “The local slaughterhouse infrastructure around the country has been decimated in the last 48 years. Passage of the PRIME Act will bring back the community abattoir and lead to a more prosperous local food system.”

The PRIME Act isn’t the first time Reps. Massie and Pingree have teamed up on a great food bill. In March 2014, the pair co-sponsored a pair of bills that would have legalized many sales of raw milk that are currently banned. Those bills, which I wrote about at the time, were “intended ‘to improve consumer food choices and to protect local farmers from federal interference.’” Neither bill passed, but their introduction established an important precedent for crafting bi-partisan food freedom legislation, a precedent that is reflected in the PRIME Act.

Given the visibility of this new bill, its bi-partisan appeal, and its growing number of co-sponsors, I’m optimistic the PRIME Act might just become law. Its passage would be an enormous victory for small farmers and consumers around the country.

Baylen J. Linnekin is the executive director of Keep Food Legal Foundation and an adjunct professor at George Mason University Law School, where he teaches Food Law & Policy.