New Food Economy: Meat plant that recalled 7 million pounds of ground beef has history of “egregious” animal welfare practices

by Joe Fassler | October 11th, 2018

In 2017, regulators warned JBS over its treatment of sick dairy cattle at its Tolleson, Arizona plant. The resulting documents may help clarify the source of this year’s Salmonella outbreak.

The JBS meatpacking plant at the center of the recent, 6.9-million-pound beef recall has a history of “egregious” animal welfare practices, documents first reported by The Arizona Republic show. The documents suggest that the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) was concerned about livestock protocols at JBS’s Tolleston, Arizona plant in question as far back as July, 2017—and not just that. The agency also seemed concerned that the company’s approach to cattle might cause it to overlook symptoms that could pose a risk to human health.

The documents also establish that sick dairy cows—a common carrier of Salmonella Newport, and likely the source of the current recall—were present at the plant to be processed for meat, and did not receive timely treatment from JBS.

On July 25, 2017, a year and a day before the first lots of recalled beef were processed at Tolleson, FSIS sent an official “Notice of Intended Enforcement” to JBS leadership, threatening to remove its federal inspectors and halt work at the plant.

“This action was initiated due to your firm’s failure to maintain or implement required controls to prevent the inhumane handling and slaughtering of livestock at your establishment,” the letter read.

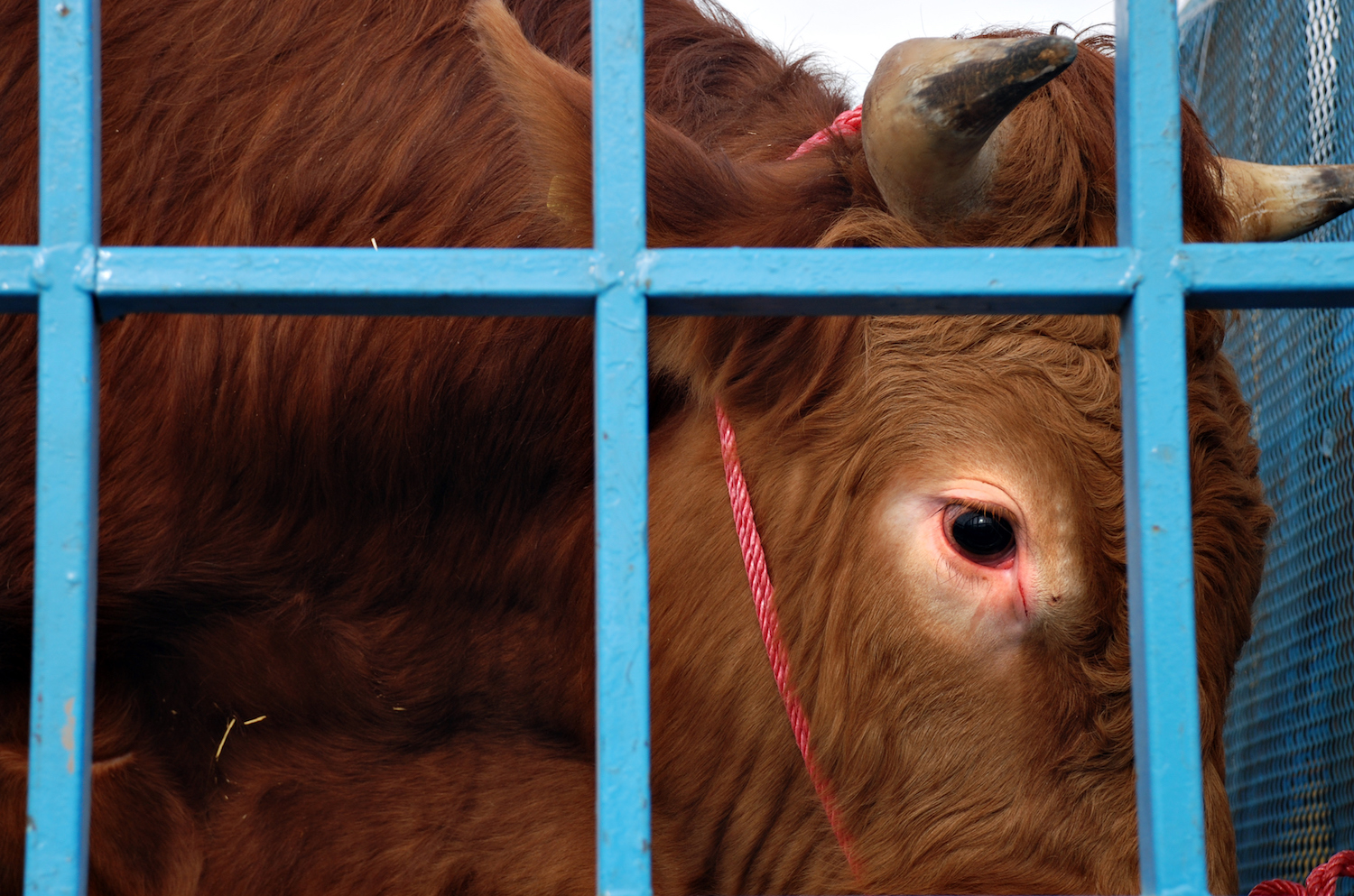

The letter went on to describe an incident involving two sick dairy cows observed by the plant’s Consumer Safety Inspector (CSI) early in the morning of the 25th. (CSIs are government employees stationed in federally inspected meatpacking plants; they work to ensure that facilities follow their written safety and sanitation plans.)

“The CSI observed one cow in Pen 19 lying on her side and unable to rise, mentally incoherent, having difficulty breathing, and repetitively making a kicking motion with its legs while moaning as if in pain,” according to the notice. “The CSI then observed another cow down in Pen 15, also lying on its side, unable to rise, mentally incoherent, and also struggling to breathe while making kicking motions with its legs.” The official determined that both cows were “in significant distress and [were] suffering.”

An FSIS spokesperson confirmed to The New Food Economy that the cows described were “dairy cows sold to the plant for meat.” (As I reported last week, dairy cow meat is commonly used pad out commodity ground beef from beef cattle. The problem is, they’re often sent to slaughter old and sick.)

An FSIS spokesperson confirmed to The New Food Economy that the cows described were “dairy cows sold to the plant for meat.” (As I reported last week, dairy cow meat is commonly used pad out commodity ground beef from beef cattle. The problem is, they’re often sent to slaughter old and sick.)

The CSI felt both cows needed to be euthanized immediately to prevent further suffering, but had trouble getting JBS staff to address the problem urgently, according to the letter. The Yard Supervisor agreed to summon an employee to euthanize the cows, but he did not immediately appear. One cow died on its own before the employee arrived, and the CSI seemed to feel that calls for prompt treatment were not taken seriously.

“The CSI repeated to the Yard Supervisor that the one remaining suffering cow needed to be knocked promptly. The CSI informed her that the second cow had died and emphatically stated that the other distressed cow needed to be knocked as soon as possible,” according to the notice. “She stated ‘I Know, I Know’ but did not do anything further.”

Ultimately, it took 15 minutes—and the CSI’s direct intervention—to bring an employee on the scene to euthanize the remaining cow. Though it’s hard to say whether the event described was an anomaly, the incident was troubling enough that FSIS sent its formal warning letter later that same day. And a follow-up letter published by FSIS suggests there were multiple issues with the animal welfare plan JBS had in place.

In a letter dated October 19, 2017, FSIS acknowledged that JBS immediately moved to appeal the decision, and ultimately asked the agency to rescind its notice. But FSIS denied JBS’s appeal then and on two subsequent occasions. Specifically, the agency cited the fact that JBS’s existing paperwork did not assure the agency that JBS employees could “identify animals in distress and take appropriate actions in a timely manner.” FSIS also noted its belief that standard operating procedures were not “sufficient to prevent the recurrence of inhumane handling due to failure to identify and verify the need for euthanasia without FSIS intervening.”

Multiple rounds of negotiation apparently followed. JBS said it had trained employees “to look for and to determine signs of distress” and had committed to performing a “daily animal welfare audit.” After months of negotiation, FSIS finally noted in the October 19 letter that it was satisfied with improvements and would rescind the notice. But the letter ended with words of admonishment that, considering the recent recall, would prove to be prophetic.

Multiple rounds of negotiation apparently followed. JBS said it had trained employees “to look for and to determine signs of distress” and had committed to performing a “daily animal welfare audit.” After months of negotiation, FSIS finally noted in the October 19 letter that it was satisfied with improvements and would rescind the notice. But the letter ended with words of admonishment that, considering the recent recall, would prove to be prophetic.

“You are reminded that as an operator of a federally inspected facility, you are expected to comply with the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA) and the regulations promulgated thereunder to ensure that livestock at your establishment are handled and slaughtered humanely,” Yudhbir Sharma, the director of FSIS’s Alameda, California office noted.

He went on: “It is also important for you to understand that FSIS has the responsibility to initiate actions if your establishment fails to operate in accordance with FSIS regulations, or conditions occur that may render products unwholesome or adulterated.”

Now, less than a year later, we know that conditions did occur at Tolleson to “render products unwholesome or adulterated.” Almost 7 million pounds of ground beef suspected to be tainted with Salmonella Newport were recalled, meaning that the meat of nearly 13,000 cattle will ultimately end up in landfill. FSIS has not been willing to provide additional details on what led to the outbreak, and JBS has not responded to repeated requests for comment. But the scenario I laid out earlier this week starts to look even more likely.

I’ve already made my speculative case that dairy cows are to blame for JBS’s latest recall, the largest recall of ground beef for Salmonella ever. As I reported previously, we already know that dairy cows, which provide about 20 percent of the nation’s ground beef supply, are the likeliest reservoir of Salmonella Newport. We know that dairy cows usually don’t enter the food supply until they get old, weak, or sick. We know that, in processing plants, dairy cow meat is used as filler in ground beef—a practice that exponentially increases its already significant public health risks, and has the potential to contaminate huge volumes of product.

The revelation of the FSIS letters makes an emerging picture even clearer. We now know that sick dairy cattle, so ill they could barely stand, were present at Tolleson just one year before the recall started. We know, too, that FSIS felt JBS employees were unable to identify excessively suffering animals and disarm problems as they happened.

Now, two other questions remain. When will FSIS provide the public with a full account of what happened at Tolleson? And if dairy cows prove to be the culprit, can we have a conversation about how to treat these animals—often sickened or weakened by the demands of high-volume milk production—as we rethink the role they play in feeding us?