Nebraska Farmer: Nebraska dairies in search of another processor

HERD EXPANSION: Nebraska’s dairy herds have been slowly expanding since 2014, and dairies of all sizes have also upgraded facilities and technologies. The state now includes six robotic dairies.

by Curt Arens | Apr 24, 2018

A lack of dairy processors is slowing industry’s expansion.

Dairying in Nebraska is a grand farming tradition. And the Nebraska State Dairy Association is one of the state’s oldest, continually operating producer organizations.

There was a day when nearly every farm milked cows. According to the 2014 Dairy Growth and Development Study, conducted by the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, dairy cow numbers in the state peaked in 1934, with 820,000 cows producing 2.9 billion pounds of raw milk, averaging 3,500 pounds of milk per cow per year. In 1965, there were 27,000 Nebraska farms with at least one dairy cow. By 1998, there were just 748.

THE GOOD STUFF: Hiland milk is one of three larger processors operating in Nebraska, along with Hiland ice cream and LALA yogurt products. There are also several on-farm dairy processors that process their own milk into dairy products.

Today, the state’s dairy cow herd has declined to 60,000 head on 155 licensed dairy farms, producing more than 1.4 billion pounds of raw milk, with an average production per cow per year in excess of 24,000 pounds. The value of that production is more than $245 million. Because of genetics, better nutrition and increased management, production in dairy has increased by 50% in the last 20 years.

It would seem, with ample natural resources, water and feed supplies, that Nebraska is on the cusp of major dairy expansion. According to Rod Johnson, executive director of NSDA, that is already happening. The state has gained about 15% in cow numbers since 2014. The one hitch that most industry professionals and farmers cite is the lack of dairy processors.

Processors in state

Only three processors are left in Nebraska, which take about one-third of the fluid milk produced in the state. These are the Hiland Dairy milk plant in Omaha, the Hiland ice cream plant in Norfolk and the LALA yogurt plant in Omaha.

Johnson says these processors receive their milk through one of the dairy cooperatives — Dairy Farmers of America or Associated Milk Producers Inc. Dean Foods also buys milk from producers in Nebraska.

The other two-thirds of the milk is sold directly, or through DFA or AMPI cooperatives to plants in northwest Iowa; in Witchita and Kansas City, Kan.; or to processors up and down the Interstate 29 corridor, including plants in South Dakota.

On-farm processors like Jisa Farmstead Cheese at Brainerd and Burbach Countryside Dairy at Hartington use only milk they produce on their own farms. Also, certified organic dairies, such as Branched Oak Farm at Raymond, do on-farm processing of their own milk.

Bygone era

Gone are the days when every small town had a local creamery. Gone are the days when the eastern part of the state was scattered with numerous milk plants producing cheese, butter, ice cream and other milk products from Nebraska farms. The last major processor to leave the state was Leprino, a mozzarella cheese maker that had a plant in Ravenna, but it left in 2013. Leprino now has Colorado plants in Fort Morgan and Greeley.

But, the “Grow Nebraska Dairy” team, consisting of members from Nebraska State Dairy Association, Alliance for the Future of Agriculture in Nebraska, Nebraska Department of Agriculture, Nebraska Extension, Nebraska Department of Economic Development and Nebraska Public Power District, is trying to change all that.

“In the hunt for new processors, we’re on a marathon, not a sprint,” Johnson says. “We put together this strong team of stakeholders, and initially focused our efforts on recruiting new producers to grow the production in the state,” he says. “We’ve actually done that. We’ve had a lot of family dairies expand and upgrade existing facilities.

“We’ve also had several farmers put in new robotic milking facilities as part of a strong effort to bring the next generation into dairying,” he says. “So, people have a very optimistic view, and it is exciting to look at the list of young producers who have become active in their dairies in recent years.”

On the search for processors

That said, the group has turned their focus to recruiting new processors. “We have to find the right company with the right fit,” Johnson says. “We need more competition for our milk,” he notes. “When we haul the milk that far from the farm, there are freight expenses to the farmer. Having a processor adds value to a Nebraska milk product.”

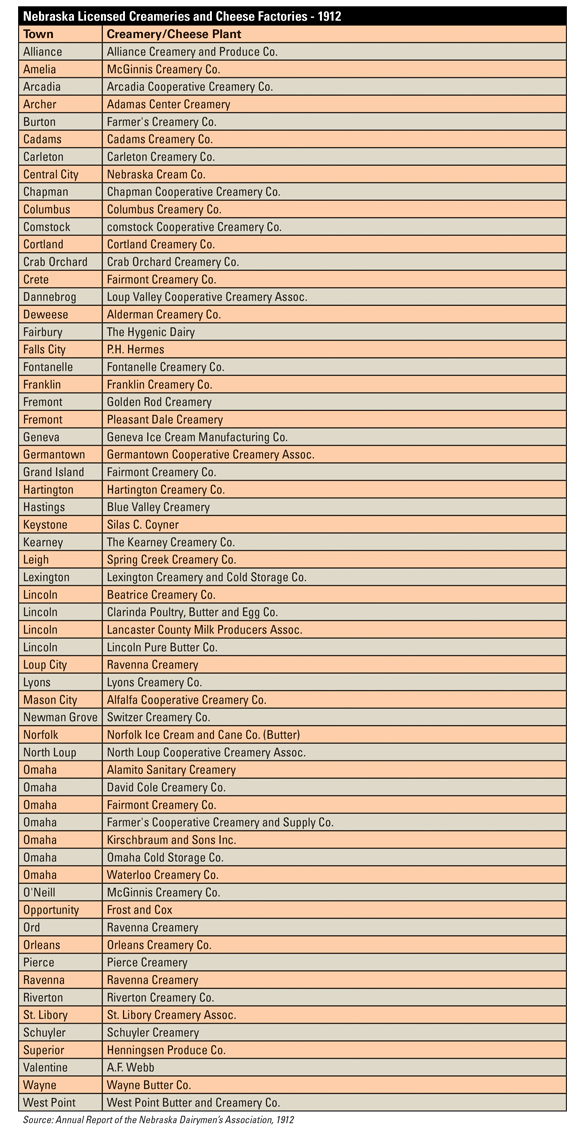

In 1912, Nebraska had 65 licensed creameries and cheese plants scattered across state.

Dairying today is big business, with substantial economic returns to the farm and to the local community. It is estimated that one dairy cow is worth about $5,000 to the local economy. Some studies have that number up to $25,000 per cow. Johnson explains that it takes about 15,000 cows to supply 1 million pounds of fluid milk for a processor.

A small modern processor might take about 2 million pounds of milk. A large processor that uses 4 million to 6 million pounds of milk would take 60,000 to 90,000 cows to fill the demand, and the company would invest upward of $300 million in a new plant. It would take about three years to complete before it was fully operational. A plant like that would offer employment for a community and have a need for numerous support services, along with providing processing and financial benefits for local dairy farmers.

To recruit a processor, the coalition has attended the World Dairy Expo in Madison, Wis., and the World Ag Expo in Tulare, Calif., along with the International Dairy Foods Association forum for processors. “We’ve retained a consultant that is well connected in the dairy industry to help us make contacts,” Johnson says. “We also wanted to make sure we had a list of communities that would welcome a processing plant and had the infrastructure to handle it. We have a list of five or six communities that would even have shovel-ready sites available.”

A processor would be a vehicle to add economic development to an area, Johnson says. “Besides the employment and services, it would open opportunities for growth in dairy production in that area,” he adds. “Besides larger processors, we would also welcome smaller, specialty-type processors that are doing very well these days.”

Learn more about efforts to recruit a new dairy processor in Nebraska by contacting Johnson at rod@nebraskamilk.org, or visit nebraskamilk.org.

Heydays of dairying

The heydays of dairying in Nebraska ran from the turn of the last century in 1900 to the mid-1930s, when dairy cow numbers peaked. The 1912 Nebraska Dairymen’s Association annual report listed 65 licensed creameries and cheese plants in the state. Seven of these were in Omaha. But they were also located in small towns from Archer to West Point and Valentine to Arcadia. West Point Creamery Co., established in 1877, is believed to be the first operational commercial creamery in Nebraska.

There were also 65 licensed wholesale ice cream manufacturers about that same time, including Niobrara Ice Cream Co. in Niobrara and W.D. Freese Cream Farm in Alma, just to name a couple. As we look to the future of dairy processing in the state, it is useful to view a snapshot of the long-standing tradition of dairying and processing from many decades ago.