NBC News: Best advice to U.S. dairy farmers? ‘Sell out as fast as you can’

Small-dairy farmers are getting squeezed out by corporate agriculture. “That is not what America is about,” a struggling farmer said.

by Phil McCausland | June 30, 2018

SMITHFIELD, Ky. — All Curtis Coombs wanted was to raise cows and run his family’s dairy farm in this slice of Kentucky hill country, less than 35 miles from Louisville. But a few weeks ago, he was forced to sell his milking herd of 82 cows, putting an end to his family’s nearly 70-year dairy business.

On a rain-drenched Monday, Coombs, his father and his uncle struggled to shove their last 13 cows into a trailer destined for auction and slaughter. As the earthy smell of manure filled the air, the men yelled for the Holsteins to move and urged them forward with the whack of a plastic stick.

The animals mooed their dissent but finally boarded the trailer. Coombs, 30, flung aside his stick and stormed a few yards away, breathing heavily. His family members wiped their brows and looked at Curtis and then the cows, which were sold for their meat at half their worth.

“It’s just hard to believe it’s over,” Coombs said later, choking up. “As long as you was milking cows, you always thought there was a hope you’d get back to it. At this point, even if there’s a Hail Mary pass, we’re done.”

Coombs is one of more than 100 dairy farmers across seven states who learned in March that they would lose their contract with Dean Foods, which runs a milk processing plant in Louisville that mainly served Walmart. Dean Foods is shutting the plant at the end of the summer because Walmart is building its own processing facility in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and will work directly with dairy farms there instead.

Many of the Kentucky dairy farmers who sold their milk to Dean Foods have not yet found anyone else to buy it instead — and like Coombs, they could soon have to sell their cows. They are just the latest of more than 42,000 dairy farmers who have gone out of business since 2000, casualties of an outdated business model, pricey farm loans and pressures from corporate agriculture.

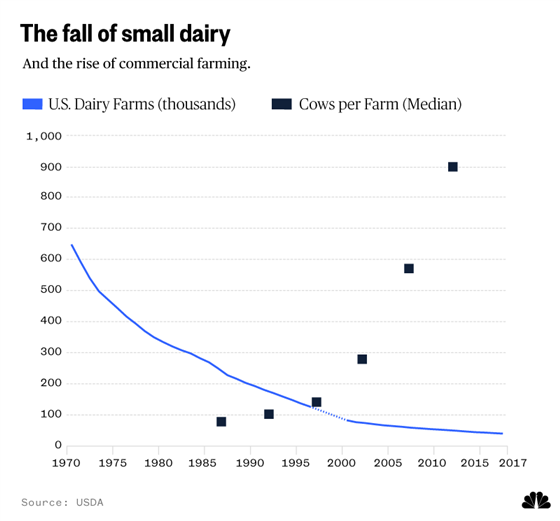

There were nearly 650,000 dairy farms in the U.S. in 1970, but just 40,219 remained at the end of 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cows are producing more milk than ever, but they’re consolidated on bigger, more efficient farms. In 1987, half of American dairy farms had 80 or fewer cows; by 2012, that figure had risen to 900 cows.

Small dairy farmers, an aging population, were some of the last U.S. holdouts against the farming industry’s pressure to grow or die — but it’s unclear how much longer they can last. Hope grew when President Donald Trump tweeted support for the dairy industry in early June at the G-7 meeting in Canada, but experts and farmers say Trump mistakenly focused his ire on trade and tariffs rather than an American industry that is increasingly hostile to small-time operators.

Joe Schroeder takes calls from dozens of struggling farmers each month at Farm Aid, an organization founded by musician Willie Nelson to keep family farmers on their land. Small dairy farmers make up a third to half of those calls, Schroeder said. The farmers, who often do the milking themselves or with family members and work 12 to 16 hours a day, tell him about the electricity being turned off and not having money for groceries. They ask advice on declaring Chapter 12 — bankruptcy designed for farmers.

“I don’t see anything that would give them hope at this point,” Schroeder said. “The best advice I can give to these folks, dairy farmers, is to sell out as fast as you can.”

The milk industry in crisis

At Walmart, shoppers in Kentucky can buy a gallon of milk for as little as 78 cents, but that’s far less than what the company paid for it or even what it cost the farmer to produce. Stores often sell milk at a loss since it’s a staple and customers may pick up more profitable items as well.

On average, farmers spend $1.92 to produce a gallon of milk and make $1.32 when they sell it to processors. This is the fourth year in a row that farmers’ milk prices have dipped below the cost of production.

“We could buy all the gallons of milk out of the grocery store, bring them home to our bulk tank, pour it in there and sell it back to them and make more money,” said Carilynn Coombs, Curtis’s wife.

Low milk prices set off a cycle in which farmers produce more milk to ensure they’re bringing in enough money to operate, leading to dairy products flooding the market and prices plummeting still further. Even when the price of milk rises, however, the cycle doesn’t end — farmers keep milking as much as they can to cash in before the price drops again. It’s a never-ending catch-22 of competition that is running dairy farmers aground.

Walmart’s decision to build its own milk processing plant highlights another issue for farmers. In a trend that extends back to the 1970s but ramped up over the past decade, corporate agriculture is increasingly taking control of all stages of milk production, which can leave small farmers with fewer places to sell their milk, said Maury Cox, executive director of the Kentucky Dairy Development Council, an advocacy group. Corporations opening milk processing plants would rather work with fewer large dairy farms than thousands of small ones, Cox added.

That, Cox said, leaves farmers asking: “What do you do in this situation when you don’t have a market for your milk?”

The question is of particular relevance to dairy farmers in the Southeast, where the industry is steeped in a certain regional irony.

While there is a surplus of milk nationwide, Kentucky and the Southeast face a net deficit of 41 billion pounds of milk annually, according to Mark Stephenson, a University of Wisconsin dairy economist. That means that even as dairy farmers in these states struggle, grocery stores there are importing milk in refrigerated trucks from the Midwest.

Why are Kentucky milk farmers being frozen out of the local market? Part of the answer lies with powerful dairy cooperatives, groups of farmers who work together to sell their milk. Dairy Farmers of America, the nation’s largest dairy cooperative, has an incentive to maintain the milk deficit in the Southeast because it gives the group’s members in the Midwest a market.

Fourteen Kentucky farmers recently tried to join the cooperative, but they were denied because the group saw them as competition, the farmers told NBC News.

John Wilson, the group’s senior vice president and chief fluid marketing officer, said that the co-op recognized “the dairy farmers in Kentucky who have been displaced face a tough situation,” but did not provide a clear reason for denying their membership.

“Membership decisions are handled on a regional basis and evaluated based on a number of factors,” Wilson said, “including farms in the area, milk volumes, supply-and-demand conditions and milk quality.”

How Canada milks differently

The struggles of American dairy farmers haven’t extended to their peers north of the border. Canada’s government runs a supply management system that controls the nation’s dairy, egg and poultry output. Canada uses the system to enforce domestic production quotas as well as limit its dairy imports and exports, which keeps prices steady and guarantees farmers a stable income — though it has a larger impact on consumers’ wallets.

Canadian dairy farmers, however, have enough extra money to fix buildings, buy new equipment and even take vacations, said John Kalmey, 66, a small-dairy farmer in Shelbyville, Kentucky, who is on the brink of ending his family’s 80 years in the dairy business and who has spoken to and visited farmers in Canada.

Small-dairy farmers in the U.S. like Kalmey, who average a salary of just over $20,000 a year if they can afford to give themselves one at all, marvel at those luxuries.

“I think it’s a shame we don’t have that same [system] here,” Kalmey said.

The disparity has also caught the attention of Trump, who placed blame for the floundering American dairy industry at Canada’s feet during the G-7 conference in Quebec. Trump attacked Prime Minister Justin Trudeau — calling him “dishonest & weak” — for Canada’s dairy tariff that keeps its farmers afloat. “Our Tariffs are in response to his of 270% on dairy!” Trump tweeted.

Kalmey and other dairy farmers, though, do not believe that an end to the dairy tariffs would be a solution. If anything, removing Canada’s protections would leave dairy farmers there in the same boat as those in the U.S. Some farmers worried that Trump is more likely to cause a trade war than open a new market for them — they fear losing the limited export market that the U.S. currently has, which could cause the price of milk to drop further.

And trade isn’t the main source of the industry’s difficulties: Dairy exports were up 2 percent between 2016 and 2017, according to the USDA. For 2018, the USDA forecasts 7 percent growth.

Loss of historic farms causes economic ripples

Gary Rock, 59, lives in Hodgenville, Kentucky, an area of rolling hills and loose rock fences, on a farm that has been passed down through his family for 300 years. After Dean Foods dropped his contract amid Walmart’s expansion, he expects that he will be the last generation to ever milk a cow on this land.

The past few years haven’t been easy. In 2012, Rock rebuilt his farm after it was hit by a tornado that destroyed all the buildings except the one where he milks his cows. The following year, he lost his legs in a tractor accident, but he kept farming. Then his only employee left after the Dean Foods announcement, so Rock began milking the cows by himself. Now, he must consider selling off portions of his farm to stay afloat.

“That is not what America is about, I’ll tell you that right now,” Rock said.

It’s not just farm families who are affected. Many of the half-dozen farmers NBC News interviewed in Kentucky pointed out that their dairy operations contribute to the local economy, from the farm equipment and feed they buy to the veterinary bills they pay. A two-year Pew Commission report found that small farms made almost 95 percent of their farm-based purchases locally, and a 2016 University of California Davis study concluded that those dollars have twice the impact locally as larger farms.

The closure of farms eliminates jobs in adjacent industries, such as manufacturing, and reduces the population of already struggling areas, said Stephenson, the dairy economist.

Things are about to get worse. Dean Foods announced last week that it would close another milk processing plant, in northern Minnesota, affecting about 50 employees and an unknown number of farmers. And the company’s management recently said it plans to close seven more plants across the country, according to John Stovall, the union president of Teamsters Local 738, which represents the employees at the closing Dean Foods plant in Louisville.

Dean Foods did not respond to requests for comment.

Walmart said it announced plans to open the Indiana plant in 2016, so the Louisville closure should not have come as a surprise. The Indiana plant opened on June 13 and provides about 300 jobs, according to Walmart. The company plans to work with 30 local farmers and supply milk to 500 stores in Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan and Kentucky.

Molly Blakeman, a spokeswoman for Walmart, said she was unsure of the size of the 30 farms that would replace the more than 100 farms that supplied Dean Foods. Walmart’s goal was to get its Great Value brand closer to local dairies, she said.

“We’re hoping to find efficiencies that will find great cost savings for our customers,” she said. “That’s what Walmart is great at.”

Growing depression over a bleak future

Bob Klingenfus, 69, who has milked cows for 54 years not far from the Coombs family, said friends, family and even the guy who sells him cattle feed have called to check up on him since he lost his contract with Dean Foods because they’re worried he might be depressed.

Klingenfus knows why they’re calling. Some dairy cooperatives have started to send suicide hotline numbers along with the farmers’ checks for milk. Agri-Mark Inc., a dairy cooperative in the Northeast with about 1,000 members, started sending the numbers in January after a third member died of suicide in as many years.

A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report found that from 2005 to 2015, suicide rates grew by 30 percent in half of rural counties, a larger increase than in urban areas. It’s an issue that the House and Senate are trying to address in the Farm Bill by introducing the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network, which would offer mental health resources.

Farmers who lose their business often go through stages of grief that some describe as similar to losing a close family member, said Michael Rosmann, a clinical psychologist and Iowa farmer who has counseled dairy farmers.

“Often they are never the same,” Rosmann said. After losing their farm, many “carry guilt and blame around with them that maybe they didn’t do enough when actually they probably put their whole minds and bodies into salvaging the farm operation. Too many factors are beyond their control.”

In Kentucky, Klingenfus is largely able to hold himself together, until he thinks of the four employees who have lived on his land and worked for him for decades. He knows he can’t afford them once he quits milking in the next couple of weeks, but the thought of having to let them go has him clutching his wife’s hand.

“They don’t want to leave,” Klingenfus said, stopping to clear his throat as tears collected at the corners of his eyes. “They can make more money right now, but this is where they want to be.”

Klingenfus tried to diversify by creating a side agri-tourism business and building a small cheese processing plant, but he doesn’t think he can break even without his Dean Foods contract.

Not many can.

After selling their dairy cows, the Coombses are focusing on growing hay and thinking about raising cattle for beef. They have to pay their farm loan in January, so their stress is only growing. More than anything, they want their two boys to understand and love the life of the dairy farmer.

Alexander, 3, keeps asking where the cows have gone and offering to go find them for his father. That brings Coombs and his wife to tears and makes them talk about ways to bring the cows back. Carilynn often throws out ideas, suggesting they open an ice cream shop, sell dairy-based soap or market their milk to the local community — but it seems all but certain that the boys won’t become the fourth generation to milk cows on this farm.

“What’s happened to us isn’t because we did anything wrong,” Coombs said. “It’s not like we had bad quality milk or treated our cows wrong. It’s just the dairy industry went through circumstances [and] we were the casualties.”

“Maybe we’ll be casualties of the battle,” he said, “but I don’t know if there’s any chance the war can be won.”