Mother Jones: “We Wouldn’t Need the Suicide Hotline If Dairy Farmers Were Getting Paid What They Deserve”

by Rowan Walrath | May 1, 2018

Milk pricing policies have left small producers at their wit’s end.

Brenda Cochran was a self-described “city girl” before she married her husband in 1973. He was a dairy farmer, so she joined him on a small farm in Pennsylvania. They’ve been working together since 1975. Cochran says that if she’d known how difficult dairy farming would be today, she never would have done it. “We have rampant corruption in the agricultural and food policies of this country,” she says. “So corrupt that until we get everybody who eats up in arms, more and more farmers are going to go out of business. They’re going to be the ones who take their own lives.”

Farmers, fishermen, and forestry workers, who are lumped together by government statisticians, have the highest suicide rate of any occupational cluster: 84.5 self-inflicted deaths per 100,000 workers, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis—that would have amounted to almost 900 suicides in 2016. (The CDC does not break out data for farmers specifically.) Cochran says she personally knows of two dairy farmers who have killed themselves since February.

In general, farmers—at the whims of large agribusinesses, supply and demand, and the weather—always face some degree of uncertainty, with some worries exacerbated by President Donald Trump’s brewing trade war with China. Members of a coalition of agricultural interests, including the National Farmers Union, co-signed a letter in April asking Congress to provide funding for helplines and mental health support groups for agricultural workers. But in dairy circles, the stress is coming to a head as a result of long-standing policies that have nothing to do with Trump.

In general, farmers—at the whims of large agribusinesses, supply and demand, and the weather—always face some degree of uncertainty, with some worries exacerbated by President Donald Trump’s brewing trade war with China. Members of a coalition of agricultural interests, including the National Farmers Union, co-signed a letter in April asking Congress to provide funding for helplines and mental health support groups for agricultural workers. But in dairy circles, the stress is coming to a head as a result of long-standing policies that have nothing to do with Trump.

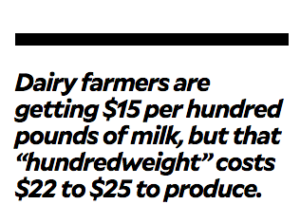

Dairy farmers in the United States are paid by the hundredweight—that’s 100 pounds of milk, about 12 gallons. Milk prices, after peaking in 2014, have plummeted to roughly $15 per hundredweight, forcing many dairy farmers to operate in the red. Tina Carlin, executive director of Farm Women United and a Pennsylvania farmer herself, says the cost of production ranges from $22 to $25 per hundredweight. “We wouldn’t need the suicide hotline, we wouldn’t need the mental health services, if dairy farmers were getting paid what they deserve to be paid,” Carlin says. She and her husband quit dairy farming in 2012, switching to beef and vegetable crops.

As president of Farm Women United, Cochran is lobbying Congress alongside Carlin to institute a $20 emergency floor price on every hundredweight of milk. The women have also advocated public hearings, but with little progress so far. Since February, Carlin has written three letters to Sen. Bob Casey (D-Penn.). An aide responded after the third one, but she has not heard anything since: “His agricultural aide said that he would circle around, and he has not circled around,” she says. Casey’s office did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Lorraine Lewandrowski, a lawyer and dairy farmer in Herkimer County, New York, agrees that a $20 emergency floor price would help in the short term. Long term, though, the dairy pricing system isn’t necessarily designed to benefit family farmers.

Here’s how it works: Class I milk—the kind you buy off the shelf—brings farmers the most money. Then come three other classes, ranging from powdered milk to cheese and yogurt. “I would say the milk pricing formula is by and away the most important thing in terms of what we end up with,” Lewandrowski says. “When the government has the formula and you go by that formula, it can work for you, or it can work against you.”

Here’s how it works: Class I milk—the kind you buy off the shelf—brings farmers the most money. Then come three other classes, ranging from powdered milk to cheese and yogurt. “I would say the milk pricing formula is by and away the most important thing in terms of what we end up with,” Lewandrowski says. “When the government has the formula and you go by that formula, it can work for you, or it can work against you.”

As it stands, she says, the system incentivizes farmers to produce more and more milk as prices drop in reaction to oversupply. She would prefer a system more like Canada’s, where farmers are not allowed to sell more than quotas set for them by the federal government.

This certainly isn’t the first time milk producers have been hit by hard times. In 2009, prices were down around $11 per hundredweight—but this time, small farmers aren’t optimistic about a rebound. “We are seeing a number of very large farms coming on line and also expanding that we didn’t see nine years ago,” Lewandrowski says—and that makes the smaller players “very, very anxious.”

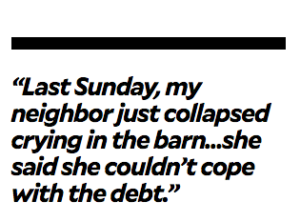

Legislation introduced in March by Rep. Tom Emmer (R-Minn.) would make mental health treatment accessible to farmers, but that bill remains with an agriculture subcommittee. “Last Sunday, my neighbor just collapsed crying in the barn,” Lewandrowski says. “Her family called, and my sister and I went over there. She just sat there sobbing and said she couldn’t cope with the debt anymore. She couldn’t take it.”

“Small and medium-size dairy farmers are really attached to their cows,” she adds. “They really don’t want to just send their cows to be slaughtered. A truck would come and take everybody, and everybody would be killed.”