KRCC.org: Drought Puts A Pinch On Southern Colorado Agriculture

File photo: In this 2017 photo, a field in Crowley County is being flood-irrigated with water from a canal that draws from the Arkansas River

Dana Cronin / 91.5 KRCC

by Ryan Maye Handy | December 26, 2018

Colorado’s farming and ranching communities are facing a season of economic losses, after summer drought dried up grass for cattle, killed crops and kept thousands of acres from being planted.

Drought in Colorado has a widespread impact on an economy where tourism and recreation play important parts, with money-drawing activities like rafting, fishing and skiing. But when it comes to agriculture – a $40 billion industry that generates $7 billion in revenue for the state, ultimately a fraction of Colorado’s GDP – Colorado is a state divided. Some counties have no ties to ranching and farming, but those that do rely on it heavily for taxes, jobs and revenue.

That divide has meant that many Colorado residents sailed through the summer mostly free of drought concerns, while ranchers and farmers faced a significantly different picture. With nearly all of Colorado experiencing some level of dryness or drought, many farmers opted not to plant at all due to lack of water, creating an economic shortfall.

That divide has meant that many Colorado residents sailed through the summer mostly free of drought concerns, while ranchers and farmers faced a significantly different picture. With nearly all of Colorado experiencing some level of dryness or drought, many farmers opted not to plant at all due to lack of water, creating an economic shortfall.

“I am certain that the dry conditions that we saw up to July — the warm and dry conditions — will have an impact on the economy,” said Peter Goble, a drought specialist with the Fort Collins-based Colorado Climate Center. “We saw plenty of crops fail.”

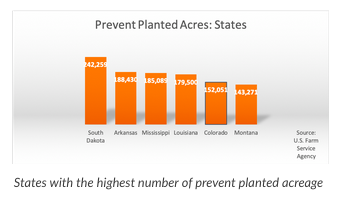

The decisions to cut back on planting have Colorado high on the list of states that had to abandon acres this planting season, with more than 152,000 that weren’t planted due to lack of water. State officials are expected to release early next year an exact tally of economic losses wrought by this year’s drought, but stories and numbers from around the state suggest that they will be noticeable.

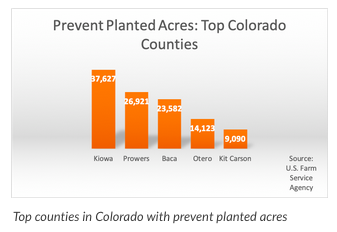

Farmers around Colorado have been forced to sell off cattle they couldn’t afford to feed, according to reports given to state officials. In southeastern Colorado, Baca, Kiowa, Otero and Prowers counties had, in total, tens of thousands of acres that went unplanted due to fears that the crops would fail, otherwise known as “prevent planted” acres. The USDA declared a drought disaster in 47 of 64 counties in Colorado, making farmers eligible for federal aid. As hay prices climbed at the end of the summer, Gov. John Hickenlooper issued an executive order easing regulations on hay transport in an effort to reduce the cost of hay for ranchers.

Farmers around Colorado have been forced to sell off cattle they couldn’t afford to feed, according to reports given to state officials. In southeastern Colorado, Baca, Kiowa, Otero and Prowers counties had, in total, tens of thousands of acres that went unplanted due to fears that the crops would fail, otherwise known as “prevent planted” acres. The USDA declared a drought disaster in 47 of 64 counties in Colorado, making farmers eligible for federal aid. As hay prices climbed at the end of the summer, Gov. John Hickenlooper issued an executive order easing regulations on hay transport in an effort to reduce the cost of hay for ranchers.

To be sure, Colorado farmers planted nearly 4 million acres of crops this year, and the losses might be significantly less than what farmers faced in 2013, another severe drought year, when more than 340,000 acres were prevent planted and as twice as many acres failed. But in the past, even losses of many thousands of acres have cost agricultural communities hundreds of millions of dollars.

Since 2002, drought has affected Colorado’s urban and rural residents differently. While Front Range and mountain residents have grappled with major wildfires, Colorado’s agricultural communities have ridden a roller coaster of good years and bad. Farmers, for instance, have prevent planted hundreds of thousands of acres over the past six years, even as vast networks of reservoirs have allowed Front Range cities to keep their residents largely free of water restrictions. This year’s summer drought was no exception.

“A lot of people were not having to plant,” said Mike Bartolo, a specialist with Colorado State University Extension. “They wouldn’t have enough water in the supply system to meet the demand of their crops so they had to fallow their land.”

Along with farmers in the southwest, Colorado’s southeastern farmers may have had the hardest year. Too little water in the Arkansas River meant that Otero County, home to the famous Rocky Ford cantaloupes and a major corn and wheat producer, lost nearly half its corn crop this year, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture records. Nearby Prowers County lost thousands of acres of wheat, sorghum and corn. And just a little bit further north, Elbert County rated 100 percent of its crop this fall as poor quality, state officials reported.

Along with farmers in the southwest, Colorado’s southeastern farmers may have had the hardest year. Too little water in the Arkansas River meant that Otero County, home to the famous Rocky Ford cantaloupes and a major corn and wheat producer, lost nearly half its corn crop this year, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture records. Nearby Prowers County lost thousands of acres of wheat, sorghum and corn. And just a little bit further north, Elbert County rated 100 percent of its crop this fall as poor quality, state officials reported.

Otero County, with nearly 15,000 unplanted acres, is the among the top five counties in Colorado where farmers chose not to plant this year due to drought, according to the USDA. Farmers there typically plant 20,000 acres of corn a year, but this year nearly 9,500 acres went unplanted, records show.

“We’ve seen probably as much prevent planted or open acres this year as we have seen in any year, clear back to even 2002,” said Chuck Hanagan, a farmer and the executive director of the local branch of the Farm Service Agency. “It’s very concerning.”

The loss in overall planted acres has triggered a domino effect that will likely spread throughout the county, Hanagan added.

“Every door on Main Street gets a percentage of that ag dollar,” he said. “And so when those ag dollars are short it’s felt in the bakery, the barber shop, the tire shop, the pharmacy.”

Prevent planted acres tell only part of the story. Colorado also recorded more than 140,000 acres this summer that were planted and failed – meaning farmers spent money on crops they cannot recoup from sales.

Insurance will offer farmers some protection, but it can’t make up for having a crop. Other insurance policies, administered through the federal Farm Service Agency, require farmers to lose half their crop to be eligible for coverage. Those policies do not take into account losses from acres that were fallowed, that is, remain unplanted, Hanagan said.

Insurance will offer farmers some protection, but it can’t make up for having a crop. Other insurance policies, administered through the federal Farm Service Agency, require farmers to lose half their crop to be eligible for coverage. Those policies do not take into account losses from acres that were fallowed, that is, remain unplanted, Hanagan said.

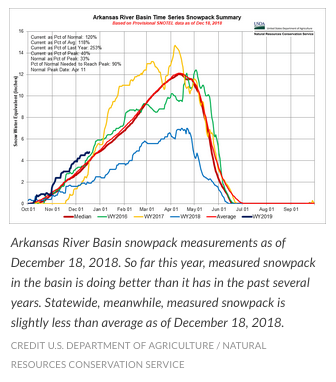

The economic damage has been done, but farmers are already looking forward to next season with hopes for a better water year. While a lack of precipitation stunted summer planting, the state’s winter wheat crop, which has a fall growing season, got a good start with plenty of moisture.

But a lot depends on the winter and spring weather cycles, said Taryn Finnessey, the senior climate change specialist with the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

State officials, meteorologists and farmers are expecting an El Niño cycle, which originates over the Pacific Ocean and tends to bring wet winters to Southern Colorado. In a place like Otero County, where farmers are heavily dependent on river water and snowmelt, that’s good news.

“We are hoping that we can get an El Niño,” said Finnessey. “We just don’t know when that is going to materialize. Or if it will materialize.”