Kansas Reflector: Kansas history suggests a path away from conspiracy theories and their violent mobs

Kansas history suggests a path away from conspiracy theories and their violent mobs

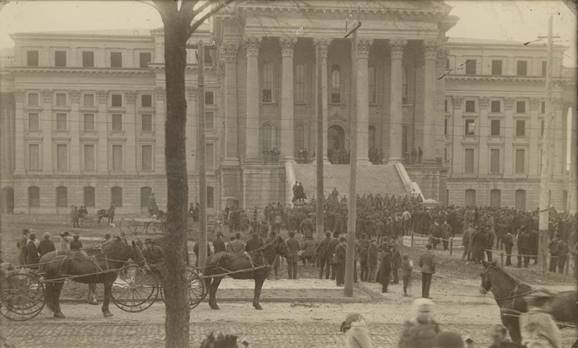

The scene at the Kansas Statehouse in Topeka on Feb. 15, 1893. According to the Kansas State Historical Society, a mob gathered "after an attempt to disarm a member of the militia during the Populist War. This dispute began when both the Republican and Populist parties claimed victory in the Kansas House elections in 1892. A number of contests were still being disputed when the legislative session began in January 1893. The conflict between the parties reached a crisis when the Populists locked themselves in the House Hall. The Republicans used a sledgehammer to break down the doors to the hall." (kansasmemory.org/Kansas State Historical Society)

The Kansas Reflector welcomes opinion pieces from writers who share our goal of widening the conversation about how public policies affect the day-to-day lives of people throughout our state. Daniel McClure is an assistant professor of history at Fort Hays State University.

A recent poll by NPR/Ipsos outlines the new reality for the United States: Conspiracies have entered the mainstream of political thought.

More than one in three Americans embrace the idea of a “deep state” seeking to undermine President Donald Trump, and 40% believe “COVID-19 was created in a lab in China.” When asked whether “a group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media,” only 47% said it was false, while 37% were “unsure whether this theory backed by QAnon is true or false” and 17% “believe it’s true.”

As Joe Biden assumes the presidency, this hyper-polarization doesn’t look good. At the same time, conspiracy theories are at the root of United States history, including in Kansas. One of the driving forces of the American Revolution was the conspiracy suggesting the British were going to deprive the colonists of their liberties — particularly the right to enslave, as the abolition of slavery in the British empire became increasingly inevitable.

As Kansans cautiously enter 2021, historian Jeffrey Ostler’s work on conspiracy theories during the state’s populist movement of the 1890s helps make sense of the seemingly insensible.

Dismissing psychological reasons for conspiracies, Ostler approaches them as a core element of politics rooted in the idea of liberty, individual rights, the sovereignty of the people, and virtuous citizens performing civic duties — i.e., “republican virtues” (republican with a small R). Just as today’s world of wealth concentration and technological surveillance provokes a nation of anxious people worried about losing their sovereign rights, Kansas populists also believed their individual liberties were threatened by forces out of their control.

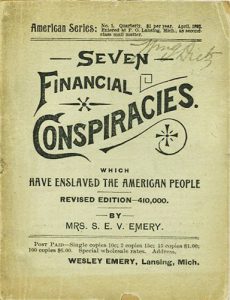

In attempting to create a third political party, Kansas populist leaders embraced a conspiracy theory drawn from Sarah E. V. Emery’s “Seven Financial Conspiracies Which Have Enslaved the American People” (printed in various editions between 1887 and 1896) to mobilize people. This pamphlet targeted the GOP — the dominant party in Kansas in the late 19th century — charging it with aiding nefarious forces that had supposedly pushed Kansans from being independent and prosperous people into a new life of “unremitting, half-requited toil.”

Sarah E. V. Emery’s “Seven Financial Conspiracies Which Have Enslaved the American People” targeted the Kansas GOP in the late nineteenth century, charging it with aiding nefarious forces that had supposedly pushed Kansans from being independent and prosperous people into a new life of “unremitting, half-requited toil.”

In response to genuine economic realities, Kansas populists saw their republican virtues under attack from these nefarious forces. In particular, Emery’s pamphlet charged Wall Street with seizing the national economy in the wake of the Civil War, as well as older national villains, such as the English, in accomplishing this anti-republican putsch. Drawing off still smoldering Jacksonian ideas about the “money power” of banks and their danger towards liberties, the new conspiracy drew on what Ostler suggests was “the need for a new antimonopoly party.” Emery’s conspiracy provided a balm for the patchwork of anxieties imagining the death of the republic.

Rather than simply dismissing beliefs in conspiracies, Ostler highlights how embracing conspiracy theories reflected the political impotency, economic hardship and indifference from mainstream political parties felt by many Kansas farmers and workers between the 1870s and 1890s. Emery’s pamphlet “helped explain the GOP’s intransigence” and was not simply a product of simplistic psychological naivety. Rather, it justified “political independence” from the GOP.

These familiar patterns offer a starting point for bipartisan engagement.

Ostler points to one inconvenient political truth for 21st century U.S. politics. A key element of unrest in Kansas was the populists’ complex relationship to capitalism and the American republic: They “accepted some aspects of a market economy, but they invoked ideals of liberty and independence to denounce monopoly, speculation, inequality of wealth, and deferential politics.”

Today’s polarization and embrace of Trumpian conspiracies reflects a similar unrest, as many people struggle within an economic system put in place by conservatives in the 1980s that has largely failed to deliver to the constituents supporting the GOP. Only the rich have prospered. Meanwhile, Democrats fail to capitalize on this discontent because they, too, were complicit.

Struggling to overturn conspiracies appears to only harden the lines of polarization. If Kansas progressives, Democrats and Republicans want to seek some sort of dialogue with folks more inclined to view QAnon as the gospel truth, they must invest party resources in outreach addressing concrete needs.

They should critique the concentration of wealth — what populists called “monopoly” — and focus on ways to keep money circulating through local communities via the support of small business and farmers who do not receive generous subsidies. And they should embrace infrastructure development aimed toward the needs of the 95% rather than the 1%.

These policies should be transparent and constructive. This is the way out — and this is progress.

Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.