Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin dairy farmers barely hanging on as crisis deepens with no end in sight

by Rick Barrett | Milwaukee Journal Sentinel | November 26, 2018

This was the year that longtime dairy farmer Jim Goodman decided to call it quits.

The third-generation farmer from Wonewoc, northwest of Madison, milked cows for more than four decades.

He loved the animals and the work, and had endured hard times, but the most recent downturn in dairy farming – now in its fourth year — was one of the worst he’d seen.

For many farmers, the price they’ve received for their milk hasn’t covered their expenses. Some have lost thousands of dollars a month, and there’s not much relief in sight as the marketplace is flooded with the commodity they produce.

Wisconsin is on track to lose more dairy farms this year than in any year since at least 2003, according to state Agriculture Department figures for dairy producer licenses.

As of Nov. 1, the dairy state had lost 660 cow herds from a year earlier, and the number of herds was down nearly 49 percent from 15 years ago. The number of dairy cows in Wisconsin has remained steady even as the number of farms has fallen. That’s because the remaining dairy operations are, in many cases, much bigger. But even some of the bigger farms have not survived.

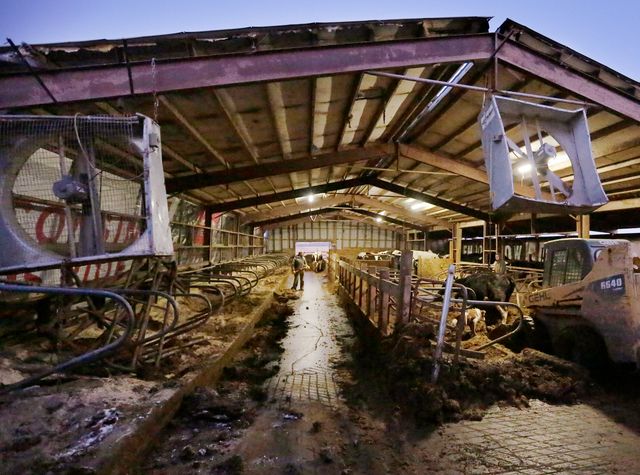

Michael Dodd milks 60 cows in a new milking parlor near Pickett. Fire destroyed the barn he rented in August and he is trying to keep his operation going as he slowly rebuilds.

Joe Sienkiewicz/USA Today NETWORK-Wisconsin

‘Getting out from under the pressure’

For many farmers, it’s no longer a matter of how they’re going to endure a fourth year of financial hardship. Rather, it’s how they’re going to exit the business and get on with their lives.

Goodman is in the final stages of selling his farm. The organic dairy farmer quit milking at the end of June and sold his 45-cow herd, whose lineage could be traced to his grandfather’s farm more than a century ago.

It was a difficult decision, but he worried that he might not have a buyer for his milk much longer as smaller farms have been getting squeezed out of business.

“Life goes on,” Goodman said, and at 64 years old he was nearing retirement anyway.

“Getting out from under the pressure has been good,” he said.

The barn Michael Dodd rented five miles from his home caught fire in August. He is struggling with debt from the fire and the low prices for dairy products.

Joe Sienkiewicz/USA Today NETWORK-Wisconsin

Farms of all sizes have been caught in the conflict between low prices for milk and other commodities, and high farm operating costs.

Sometimes it’s even tough to exit dairy farming without losing a large amount of money.

“If you’re thinking about selling your cows, they’re probably worth considerably less than they were a few years ago,” said Goodman, who’s also president of the National Family Farm Coalition that represents about 30 different farm groups.

“From what I’ve read from dairy economists, no one is predicting that things are going to get substantially better. Most are saying it’s going to stay kind of like it is now, which is not very reassuring,” Goodman said.

Trying to get out of debt after fire

Michael Dodd, a dairy farmer in Pickett, near Oshkosh, says he’s losing about $3,200 a month from milking 61 cows.

He’s more than $500,000 in debt, behind on bills, and struggling to recover financially from an Aug. 11, 2017, fire that destroyed much of his milking operation.

It was 11 p.m. when Dodd and his wife, Ashley, got a call that the barn they rented five miles from home was engulfed in flames.

The glow in the sky was visible from two miles away, Dodd said, and as he got closer there were volunteer firefighters everywhere.

His cows broke out of the barn, smashing through boards to escape and then taking shelter in a building 34 feet away. The heat from the fire was so intense it melted the canvas sides of that building and left the cows choking on thick black smoke.

At that point, “We let them out and just let them run,” Dodd said.

His cows survived the fire, but 15 were so sickened from the smoke they later had to be destroyed.

His insurance wasn’t nearly enough to cover his losses, Dodd said, and he went from having a profitable milking operation to one that didn’t produce any income for six months.

He fell behind on loan payments and bills, including $1,200 a month in barn rent, and now that he’s milking again the price he gets for his milk doesn’t cover his costs.

Still, the 29-year-old farmer who worked in a foundry so that he could afford to start farming, refuses to give up.

“It’s in my blood. There’s nothing else I want to do,” he said.

Dodd says he could pay down his debts if he could afford barn repairs and increase his herd size to 90 cows.

His landlord has made repairs as Dodd could pay him, and he needs about $10,000 to finish the work.

As some other farmers have done, Dodd has started a Go Fund Me campaign to get some help from the public.

“We were making money … and then everything went downhill after the barn burned,” he said.

Wisconsin lost 500 dairy farms in 2017, and about 150 have quit milking cows so far this year, putting the total number of milk-cow herds at around 7,600 — down 20% from five years ago.

Wochit

Ashley Dodd has a job on another farm which has several hundred cows.

“She’s sick of the stress and of being broke … but I am very stubborn,” Michael said.

Crisis calls increase

This winter, more dairy farmers will have to decide whether to quit before their situation gets worse or they have to borrow money for spring planting.

Dodd says he can hang on for another couple of months, but as the bills pile up he’s not so sure beyond that.

“Every time something breaks here, it costs money. I have two tractors with rotted, worn-out tires, but it costs $1,200 to $1,800 apiece to replace them. I spent $5,000 to fix a hay baler, and that was just for the parts.”

Michael Dodd’s cows survived the fire that destroyed the barn he rents.

Joe Sienkiewicz/USA Today NETWORK-Wisconsin

Crisis calls to the state Agriculture Department’s farm center are up about 10 percent this year, and they’ve been on the rise for several years as dairy farmers seek answers to their financial predicament.

“The farmers calling in are under a high level of stress. And no two cases are the same,” said Krista Knigge, a Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection division administrator who runs the farm center.

‘Nothing in dairy farming makes any money’

At Wylymar Farms, an organic dairy farm in Monroe, Emily and Brandi Harris face a sharp drop in their income next spring if things don’t improve soon.

Their farm cooperative has warned them to expect about a 33 percent cut in their milk price after their current contract expires in May.

Emily is a fourth-generation farmer. A couple of years ago she and Brandi were milking 50 cows, but now it’s about 30 as they’ve tried to reduce expenses.

“Everything is hard now. The things I used to do to save money really don’t work anymore,” Emily said.

Brandi has taken a job off the farm to get health insurance and cover living expenses.

Emily said she doesn’t plan to quit farming, though she empathizes with farmers who face that precipice in their lives, and she could face it, too.

“There’s just nothing in dairy farming that makes any money right now,” she said.

“A lot of our income needed to make repairs, or to do something like replace a roof, used to come from selling 20 heifers for about $20,000. Now, heifers aren’t worth $300 each. We’ve lost any extra income we used to have.”

“Two dairy farms a day are going broke in Wisconsin,” she added. “It’s a sad deal.”