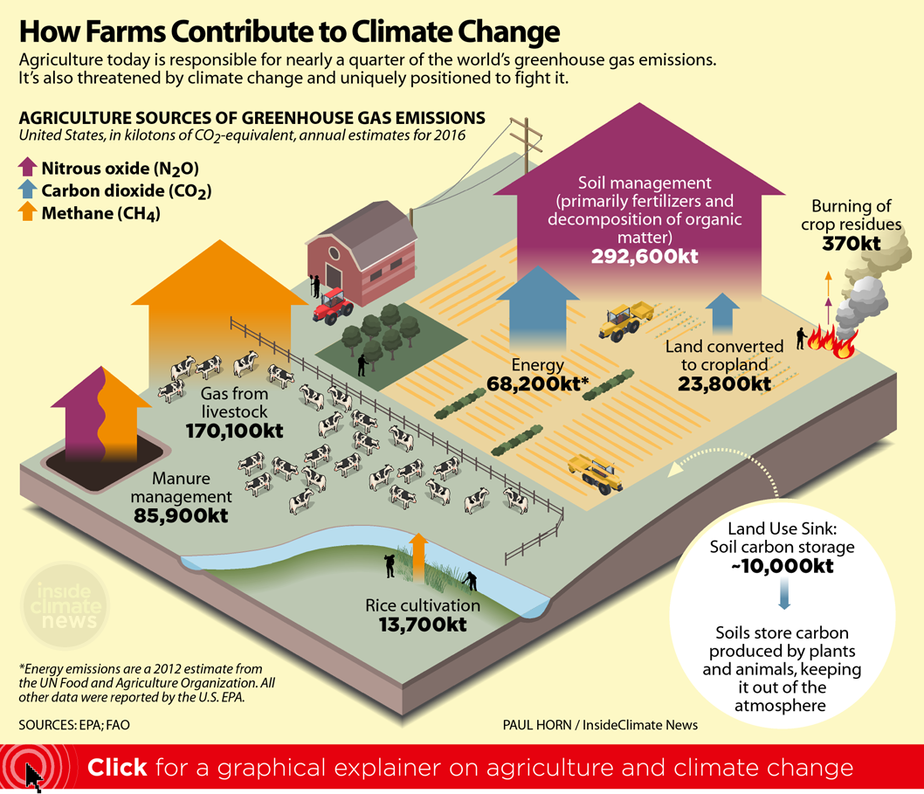

Inside Climate News: The Farm Bureau: Big Oil’s Unnoticed Ally Fighting Climate Science and Policy

by Neela Banerjee, Georgina Gustin, John H. Cushman Jr. | December 21, 2018

While big oil and gas companies provided the cash for anti-regulation campaigns, the farm lobby offered up a sympathetic face: the American farmer.

When Republican Rep. Steve Scalise stepped to the dais in the U.S. House of Representatives in July and implored his colleagues to denounce a carbon tax, he didn’t reach for dire predictions made by the fossil fuel titans that pushed for the resolution.

Instead, he talked about America’s farmers.

“Why don’t we listen to what the American Farm Bureau Federation said about a carbon tax?” the Louisiana congressman said, holding up a letter from the group, the nation’s largest farm lobby. “‘Agriculture is an energy-intensive sector, and a carbon tax levied on farmers and ranchers would be devastating,'” he read.

Advocacy groups with close ties to the oil billionaires Charles and David Koch had urged House leaders to get the anti-tax resolution approved.

When the measure passed, by a big margin, it proved—not for the first time, nor the last —the Farm Bureau’s role as a powerful defender of the nation’s fossil fuel interests.

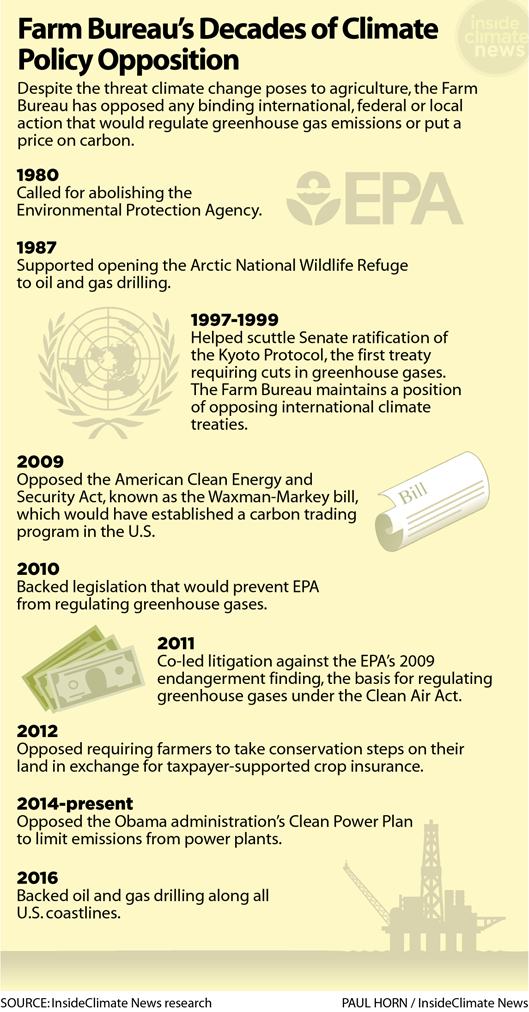

For more than three decades, the Farm Bureau has aligned agriculture closely with the fossil fuel agenda. Though little noticed next to the influence of the fossil fuel industry, the farm lobby pulled in tandem with the energy lobby in a mutually reinforcing campaign to thwart the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, legislation like the Waxman-Markey economywide cap-and-trade plan, and regulations that would limit fossil fuel emissions.

This article, part of a series exploring agriculture’s role in climate change and the influence of the Farm Bureau, examines the close ties between the two industries as they fought to undermine climate policy.

In pursuit of their common goals, the fossil fuel industry and the Farm Bureau worked to sow uncertainty about the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change and the economic consensus on how to solve the problem. Fossil fuel companies spent hundreds of millions of dollars to develop a network of think tanks and friendly lawmakers who gave climate denial political credibility as part of a decades-long misinformation campaign. The Farm Bureau provided a national grassroots network that was hard for Congress to oppose.

“Everyone on the Hill knew that there was a division of labor,” said Joseph Goffman, a former associate assistant administrator for climate at the Environmental Protection Agency and executive director of Harvard Law School’s environmental and energy program. “Oil companies argued that consumers would pay a price at the pump for regulation of fossil fuels. And the farmers could argue that they were a far more economically sensitive group of fuel users and would be seen more favorably than oil would be.”

The Farm Bureau has insisted that attempts to control greenhouse gas emissions would drive up costs for fuel and fertilizer. But other influences are also at work. Farmers’ cooperatives run their own fuel businesses. Farmers increasingly earn income from the production of fossil fuels on their land. And the industries are major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Climate regulations, in the long run, would reshape them both.

To this day, the Farm Bureau does not acknowledge the overwhelming scientific consensus that global warming caused by human activities is a reality and that it poses grave risks to agriculture.

“These guys have been so dug in on climate that they don’t want to entertain any discussions of potential ways forward on this,” Joseph Glauber, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said of the Farm Bureau. “If they discount all the benefits from cap and trade and a carbon tax because they don’t believe in climate change in the first place, then they view all these efforts as an energy tax—as all costs and no benefit.”

“These guys have been so dug in on climate that they don’t want to entertain any discussions of potential ways forward on this,” Joseph Glauber, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said of the Farm Bureau. “If they discount all the benefits from cap and trade and a carbon tax because they don’t believe in climate change in the first place, then they view all these efforts as an energy tax—as all costs and no benefit.”

Farm Bureau officials declined to be interviewed for this article. In emails, Farm Bureau spokesman William Rodger said common policy goals have “on occasion, aligned AFBF with other energy-based associations such as API [American Petroleum Institute]. This is hardly unusual; coalitions based on a common view of one or two issues is a consistent feature in policy advocacy in Washington.”

“Our farmers and ranchers determine our policies, and AFBF pursues legislative and regulatory strategies to achieve our members’ goals,” he wrote.

In its fight against regulation, the Farm Bureau has long capitalized on the idea that farmers know what’s best for their land.

“The fundamental position on climate change for farmers is that the government will come in and tell you what to do, and that’s anathema to American farmers,” said Robert Young, a former chief economist for the Farm Bureau. “The government does that all the time. The farmer’s feeling is that, ‘I want to decide what I want.'”

Greg Dotson, former Rep. Henry Waxman’s top environmental aide from 1996 to 2014, noted that the Farm Bureau’s relentless opposition to climate policies could eventually end up hurting the farmers it represents as climate change worsens heat, droughts and extreme weather.

“The lost decades due to inaction will only make it that much harder to avoid the worst effects of climate change,” he said. “Mitigation that might have been relatively easy in 1990, straightforward in 2000, or ambitious in 2010, will be a stretch in 2020. We must come to terms with the fact that, try as we may—and I believe we will try very hard—we may well have terrible losses.”

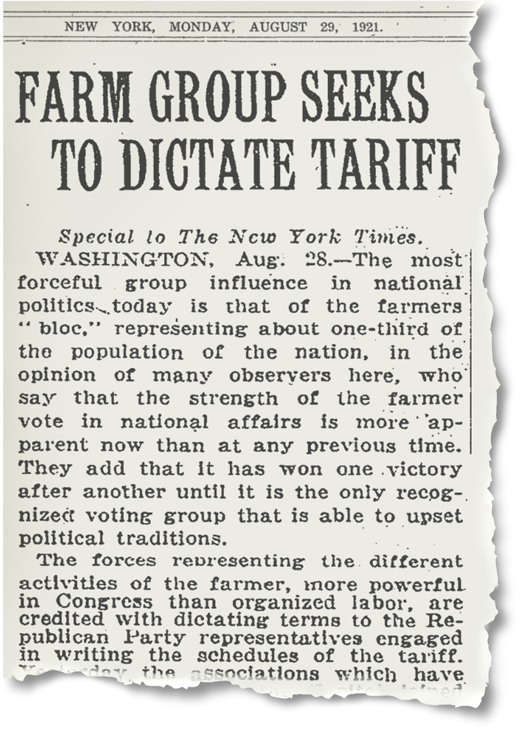

Conservative and Vast, a Powerful Lobby Is Born

The Farm Bureau’s first chapter was founded in 1911 in Broome County, New York, by corporate interests as an antidote to populist farm movements that were sweeping the Great Plains. Midwest agrarian reformers were protesting low commodity prices and high rail freight rates set by East Coast corporations. The companies, in turn, saw the movement’s expansion as a threat to capitalism.

Chapters opened in counties all over the country. State bureaus followed, and in 1919, the national American Farm Bureau Federation was established in Chicago.

Chapters opened in counties all over the country. State bureaus followed, and in 1919, the national American Farm Bureau Federation was established in Chicago.

The group presented a unified political voice and lobbied for longer-term credit, protective tariffs and crop insurance. Immediately, it created powerful alliances within Congress. The New York Times in 1921 called the new lobby “the most forceful group influence in national politics today,” “more powerful in Congress than organized labor.”

Hewing to its conservative origins, the Farm Bureau built its power as it fought antitrust laws and other restrictive policies over the next decades. But with the formation of the EPA and passage of the country’s first landmark environmental laws in the 1970s, the bureau’s anti-regulatory agenda kicked into higher gear as the group found common ground with the fossil fuel industry. “It’s really, really hard to escape the suspicion that there’s a big ideological overlay here between them,” Goffman said.

Food and Fuel: Dependent, and Getting More So

The alliance between the Farm Bureau and the fossil fuel industry was rooted in a shared anti-regulatory ideology. It flourished because their financial interests are intricately intertwined. Energy, after all, is both consumed and produced on American farmland.

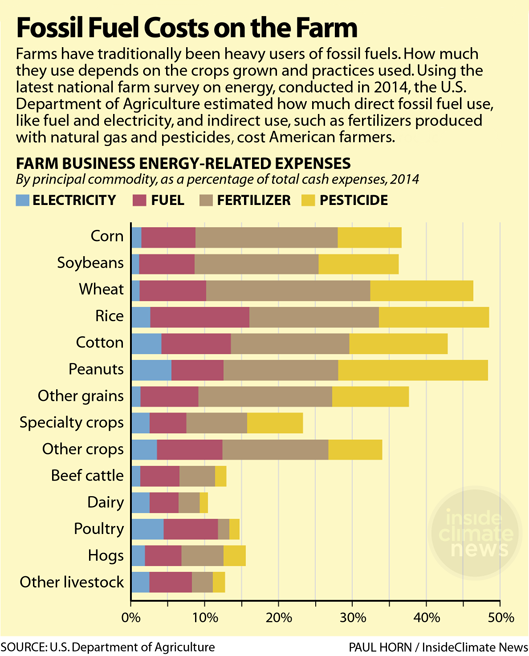

Oil powers farm machinery. Coal generates a greater percentage of the power at rural electric utilities than in the rest of the country. Natural gas is the feedstock for nitrogen-based fertilizer. Pesticide production and application rely on fossil fuels. All told, fossil fuel-related costs make up a significant chunk of farming expenses, between about 10 percent and nearly 50 percent, depending on the type of crop or livestock, according to USDA data.

“The industrial model of agriculture is very energy intensive and fossil fuel-dependent,” said Ben Lilliston, director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, a farm research organization. “The equipment is getting bigger and bigger and requires more fuel.”

But it isn’t just about farmers—the wider agriculture community earns income from the food-fuel nexus. In 1930, state farm bureaus in Ohio, Michigan and Indiana formed the Farm Bureau Oil Company. And in less than 30 years, it owned 1,200 wells, a pipeline network and refining operations on U.S. farms.

Today, nearly a third of the country’s roughly 1,500 farming cooperatives sell diesel and other petroleum products, generating more than $17 billion in net sales in 2016. And some still own large oil exploration, pipeline and refining ventures.

State farm bureau affiliates also sell insurance products, and some run for-profit funds that invest that insurance money in fossil fuel businesses. The insurance subsidiary of the Iowa Farm Bureau, the country’s wealthiest state bureau, owns a fund called FBL Financial that in 2017 had about $462 million invested in fossil fuel companies, including refineries, pipeline corporations and oil and gas producers, according to federal filings.

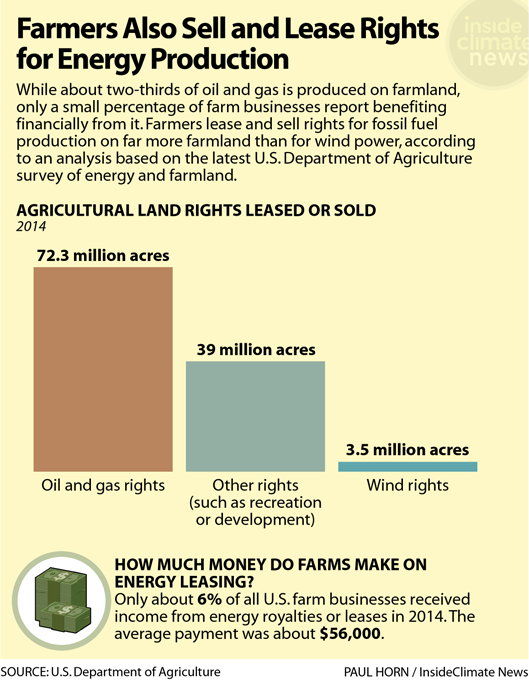

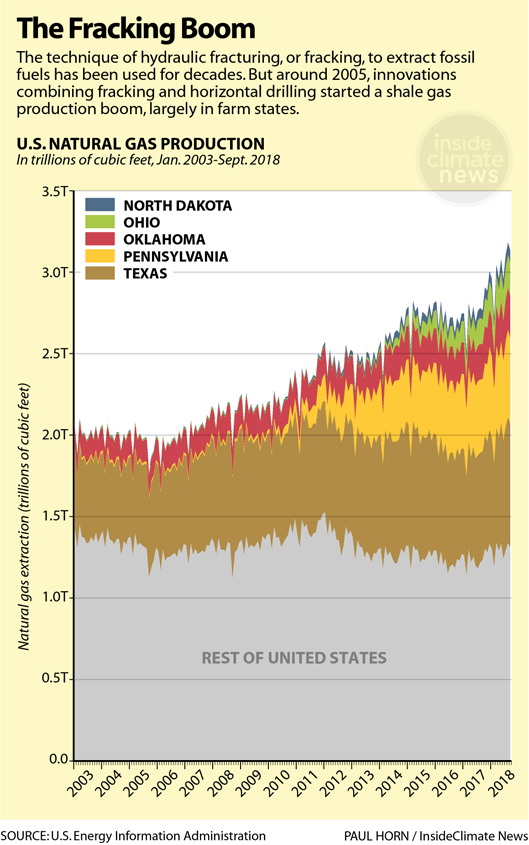

The agriculture and fossil fuels lobbies have diverged over biofuel, which the oil refining industry sees as a threat to profits and farmers view as an economic lifeline. About 40 percent of the U.S. corn crop goes to making ethanol. But farmers also lease land for oil and gas development, increasingly so in regions opened up by fracking.

Strikingly, farmers in fracking-heavy counties have been more likely to take acreage out of the Conservation Reserve Program, the environmental centerpiece of farm policy.

The program pays farmers to set aside certain environmentally sensitive lands to avoid soil loss. At its peak in 2007, it enrolled 37 million acres. USDA researchers noted that acreage enrolled in the program declined by 36 percent between 2002 and 2015 in counties where the oil and gas boom took place, compared to 25 percent in counties where it didn’t.

The appeal of oil and gas income undermined soil conservation efforts that could play a big role in addressing climate change.

“All of a sudden, this resource boom comes along and all of that momentum was undercut,” said Ted Auch, a program coordinator with The FracTracker Alliance, an environmental data group that analyzed the relationship between fracking and conservation lands. “Writ large, that’s having an impact on progressive agriculture, all the way from South Dakota to Ohio.”

Kyoto and the Spread of Climate Misinformation

The Farm Bureau called for abolishing the EPA in 1980, and later fought efforts to bolster air and water quality standards and protections for endangered species—often in partnership with the American Petroleum Institute and other fossil fuel groups.

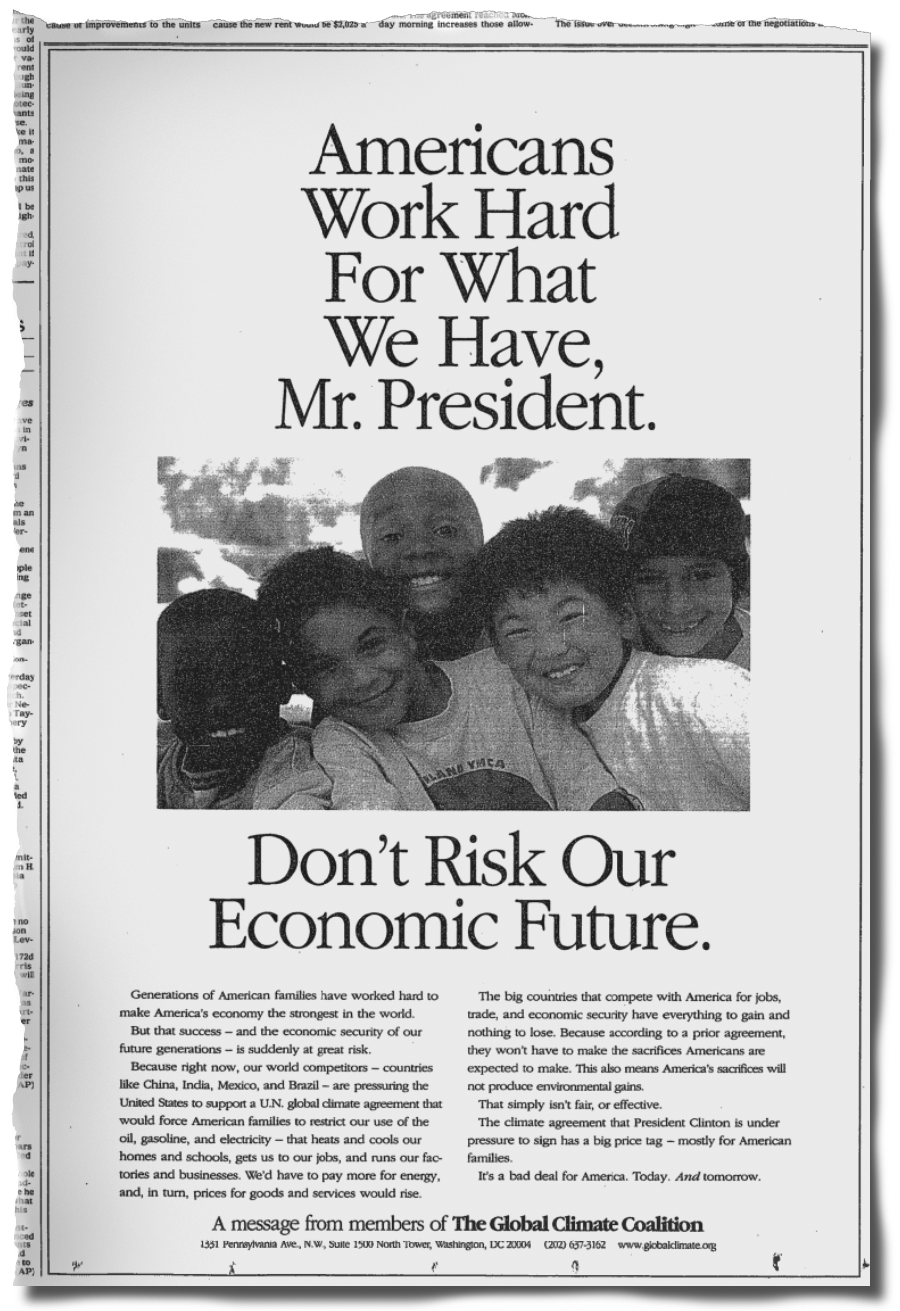

The alliance strengthened when the Farm Bureau became a member and powerful ally of the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), a group of industrial lobbies, including API and Exxon, that spearheaded corporate opposition to the Kyoto Protocol. The treaty was the first to require wealthier nations to cut global warming pollution. Early on, carbon trading was seen as the instrument of choice to achieve emissions cuts at the least cost.

The GCC ran this ad in The New York Times in June 1997 opposing the Kyoto Protocol. (click to enlarge)

The GCC’s message was simple: Climate science was too uncertain to warrant action, and international accords such as Kyoto unfairly favored other countries at the expense of American wealth and power.

As President Bill Clinton was on the verge of signing the treaty in 1997, the Farm Bureau joined a smaller offshoot of the GCC to launch a $13 million public relations campaign to derail Senate approval of the treaty.

“The Farm Bureau has a grassroots network that was immensely valuable,” recalled Frank Maisano, a former spokesman for the GCC. It “used vehicles of communications that they had back then, such as their radio networks and newspapers, to get the message out about Kyoto to farmers.”

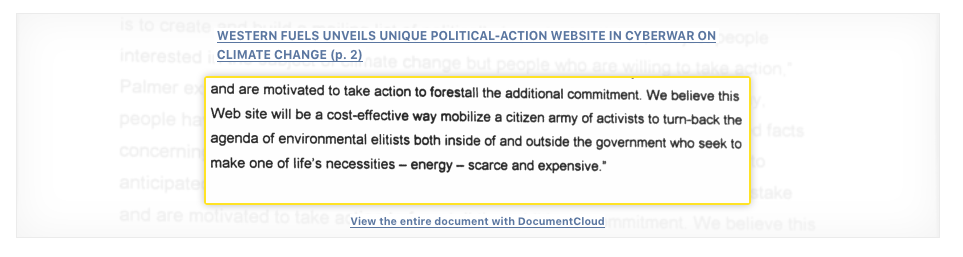

Another fossil fuel lobbying group also turned to farmers for help. The Western Fuels Alliance chose Iowa for a grassroots effort in farm country to denounce the Kyoto Protocol. It got thousands of farmers, small businesses and unions in the state to sign an open letter to Clinton and Vice President Al Gore opposing the direction the Kyoto talks were taking.

The alliance then hired consultants to produce a page on the World Wide Web, the new thing at the time, where other interest groups could join in the campaign to forestall the protocol.

Fred Palmer, the Western Fuels Alliance’s chief executive, called the online campaign “a cost-effective way [to] mobilize a citizen army of activists to turn back the agenda of environmental elitists both inside and outside the government.”

Dean Kleckner, the Farm Bureau’s president at the time of the Kyoto negotiations, was among many of the group’s leaders to recite the mantra that man-made climate change was an unproven theory.

Dean Kleckner, American Farm Bureau Federation president from 1986 to 2000, shown here with then-Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, argued human-caused climate change was unproven. Credit: Douglas Graham/Congressional Quarterly via Getty Images

“But there is still a legitimate debate, despite what we have heard, about the magnitude of those changes, their significance and the relative contribution of natural versus human causes including agricultural production.”

That year, a resolution that stated the Senate opposed the U.S. joining the treaty was introduced by coal state Sen. Robert Byrd (D-W.Va.) and farm state Sen. Chuck Hagel (R-Neb.). It passed 95-0. Hagel was later awarded a “Friend of the Farm Bureau” title for his work. The U.S. signed the Kyoto Protocol in November 1998, but the Clinton administration never submitted it to the Senate for approval. The Bush-Cheney administration later abandoned the treaty.

The Heartland Partnership

The Farm Bureau worked closely over the next decade with one of the most vocal groups disputing mainstream climate science—the Heartland Institute, a conservative advocacy organization that had ties to fossil fuel interests.

Heartland enlisted top Farm Bureau economists to co-author reports that expanded the argument against limiting fossil fuel emissions by saying a cap would cripple farms by raising costs. They challenged the claim that farmers would gain income by participating in a global effort to offset carbon emissions.

Through its relationship with Heartland, the Farm Bureau went from denying the science to disputing the mainstream economic view that effectively addressing climate change requires a price on fossil fuel pollution.

Heartland issued a report in 1998 aimed at Capitol Hill and co-authored by Terry Francl, the Farm Bureau’s chief economist, which proclaimed the Kyoto Protocol would have “dramatic, negative effects on U.S. farmers.” Energy costs would rise by the equivalent of a quarter to half of net farm income, the authors said. They warned that hundreds of thousands of farmers would have to choose between bankruptcy and selling out. A half-dozen reviewers and consultants lent advice to the primary authors, according to the acknowledgments. Each one was a proponent of climate denial.

Other analysts publishing in peer-reviewed economic journals did not see such dire effects. Not only would farmers adapt to rising prices by changing their farming practices, they argued, but the resulting environmental benefits would pay off for society at large.

Other analysts publishing in peer-reviewed economic journals did not see such dire effects. Not only would farmers adapt to rising prices by changing their farming practices, they argued, but the resulting environmental benefits would pay off for society at large.

Economists Paul Faeth and Suzie Greenhalgh of the research organization World Resources Institute debunked the Farm Bureau’s math in a 2000 economic analysis, saying it hinged on serious flaws in its assumptions and methodology.

“We find that the implementation of policies that address climate change will not be an economic disaster for U.S. agriculture,” they wrote. “The Kyoto Protocol would reduce net cash returns by less than one percent. With the right policy setting, net cash returns could be positive.” Cap and trade, for example, would encourage farmers to cut their emissions through fuel efficiency and climate-friendly farming practices, allowing them to earn emissions credits that they could then sell to other polluters.

This “would help farm income, enhance the environment, and reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions while cutting soil erosion and nutrient pollution,” they wrote.

Over the years, Heartland and the Farm Bureau continued to cultivate their argument that carbon trading would be ruinous for farms and ranches. In 2003, as they were about to publish another report on the subject, Joseph Bast, president of Heartland, and then-Farm Bureau President Bob Stallman testified at a Congressional hearing on climate change and farming.

“Even with the best, most comprehensive agricultural offsets program, the agricultural sector will lose under cap and trade,” Stallman said at the hearing. He estimated the short-term costs to farmers at $5 billion, rising to $13 billion or even more.

“Truthfully, any figure I or anyone else gives you is really not much more than an educated guess. There are so many unknowns and assumptions and estimates that are built into this debate. No one can look you in the face and tell you with certainty what is going to happen,” Stallman said, citing Bjorn Lomborg, a well-known contrarian whose views on climate change fall outside established science.

The economic argument depended on the same emphasis on uncertainty that denialists had used to sow doubt about the science.

Eventually, this approach would underpin the Farm Bureau’s stance against a House bill known as Waxman-Markey. The measure attempted in the first years of the Obama administration to put an economy-wide cap-and-trade system in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Bob Stallman (center), American Farm Bureau Federation president from 2000 to 2016, argued to farmers and government leaders that the economics around climate policies were too uncertain and farms would suffer. Credit: Elizabeth Moore/USDA

The Agriculture Department’s bureau of economic analysis argued in 2009 that cap-and-trade legislation would buffer farmers from the costs of meeting a mandatory cap on emissions. Revenues from pollution offsets would overtake the increased cost of fuel, “perhaps substantially,” it said.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimated that new farm income from the proposed cap-and-trade system would be about $20 billion a year by 2050. This was a new challenge to the Farm Bureau’s contention that climate regulations would cripple the industry.

The Farm Bureau joined a campaign called “Energy Citizens” led by the American Petroleum Institute in summer 2009 to organize opposition to cap and trade. It also launched its own effort through its state affiliates to pressure senators in particular to reject the bill and organized 120 farm groups to denounce it.

In Congress, the Farm Bureau won concessions in the House version of the Waxman-Markey bill: Farmers would not have to limit their emissions, yet they could make money by selling emissions credits to other polluters. The Farm Bureau continued to oppose the bill. It was never introduced in the Senate. Cap and trade was declared dead in 2010, after the midterms swept in hardline conservatives backed by the Koch brothers and flipped control of the House to Republicans.

Farmers Got the Bureau’s Message

In 2010, a group of 47 leading agriculture and climate researchers organized by the Union of Concerned Scientists wrote to Stallman expressing deep dismay at the Farm Bureau’s continued denial of mainstream climate science.

“Your organization’s position does not reflect the consensus opinion of the science community or the scientific literature. Your stance represents the position taken by a relatively small number of climate change deniers,” the group said. The scientists offered to provide a detailed briefing of the current science. The Farm Bureau brushed them off.

Many farmers have readily accepted the threads of lobbyists’ arguments—that climate science is doubtful and solutions are best kept out of the hands of government.

Linda Prokopy and colleagues at Purdue and Iowa State universities found in surveys in 2011 and 2012 that while 66 percent of corn producers said they believed climate change was occurring, only 8 percent said human activities were the main cause. A quarter thought natural variations were at work, and a full 31 percent said there wasn’t enough information to show that global warming was underway.

A separate series of focus groups among Midwestern farmers around the same time illuminated the breadth of their resistance to climate solutions.

“Many participants noted that they did not believe the science nor trust scientists,” the researchers reported. “Many speculated that scientists had created climate change to reap money or that they had simply made it up.”

A pump jack at oil well and fracking site situated in cotton field in Shafter. Kern County, located over the Monterey Shale, has seen a dramatic increase in oil drilling and hydraulic fracking in recent years. San Joaquin Valley, California. (Photo by: Citizens of the Planet/Education Images/UIG via Getty Images)

Prokopy and her colleagues wrote that farmers’ views may be profoundly influenced by repeated messages from trusted advisers, including the Farm Bureau.

“Agricultural interest groups, principal among them the influential American Farm Bureau Federation, have consistently voiced opposition to climate policy and legislation and have cast doubt on links between human behavior and climate change and the need for mitigation of GHG emissions,” they wrote. “These intermediaries selectively choose information they receive and act as gatekeepers by taking the raw science and adding their ‘spin’ to it.”

States Feel the Weight of the Farm Bureau, Too

Today, the Farm Bureau and fossil fuel industry’s messages—on the supposed uncertainty of climate science and purported unfairness of making the U.S. a leader in addressing the problem—echo broadly across farm states and in the Trump administration.

The administration withdrew from the Paris Agreement, the global climate treaty signed by President Obama. It repealed Obama’s Clean Power Plan aimed at shutting the most polluting coal plants. It opened more public lands to fossil fuel development.

American Farm Bureau Federation President Zippy Duvall (right) traveled with Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue to a farm in Colorado in May 2018. Credit: Lance Cheung/USDA

At the state level, the Colorado Farm Bureau worked with oil and gas interests this fall to defeat a proposed ban on drilling. The bureau launched a counter ballot measure that would require the state to compensate landowners for financial losses from a drilling ban. Protect Colorado, an oil industry group, financed the measure. But farmers served as the face of the effort, gathering the signatures and promoting the message that income from drilling on farmland keeps them afloat.

“Putting a corporate oil executive out front on some issue is of limited utility because it’s seen as self-serving,” said Eric Sondermann, a political analyst and strategist in the state. “So industry finds third party allies, and farmers are very sympathetic allies.”

Both ballot measures failed, preserving the status quo.