Hatching a Conspiracy: A BIG Investigation into Egg Prices

Hatching a Conspiracy: A BIG Investigation into Egg Prices‘More hens, less income!’ So said the United Egg Producer economist Donald Bell in 1994. The industry has gotten more consolidated ever since. And avian flu is just the latest excuse to hike prices.

This issue is part one of a three-part series on the egg industry. It is written by antitrust lawyer Basel Musharbash, based in part on a report he authored for Farm Action.

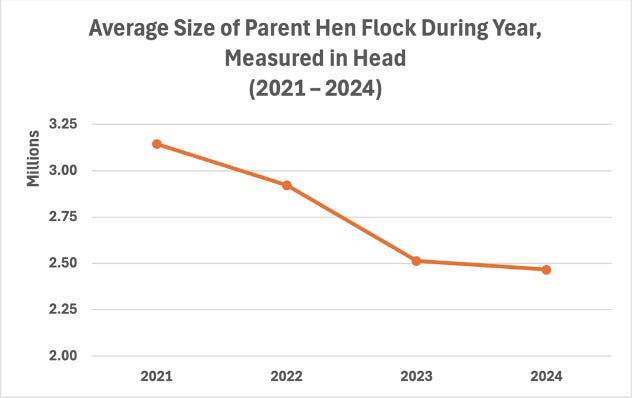

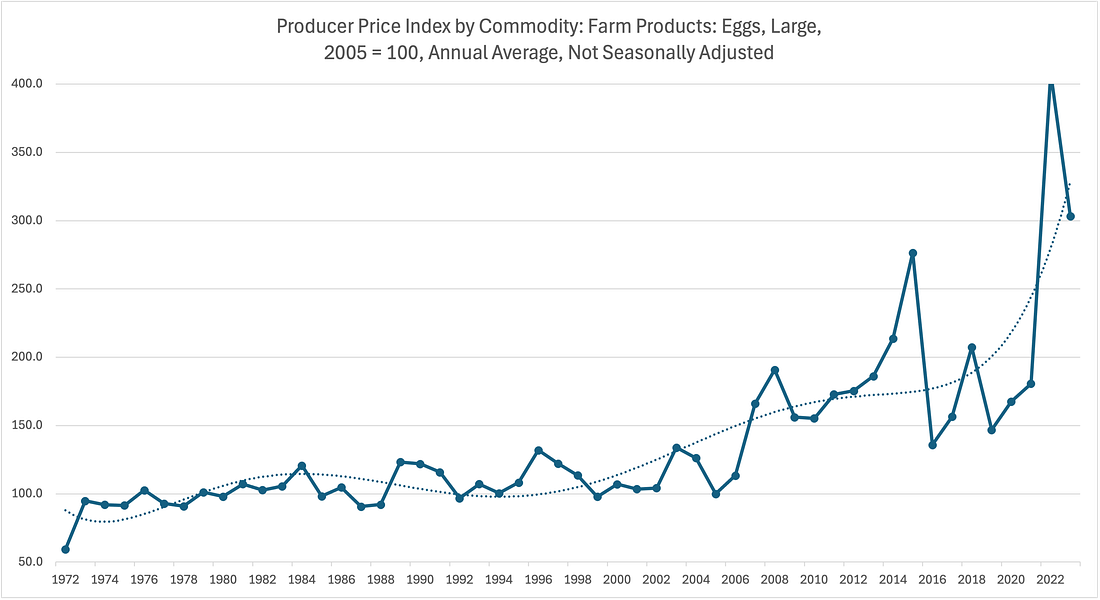

Over the past two months, egg prices have become a political football. Journalists are reporting in depth on the industry, egg consolidation has come up in Congressional antitrust hearing, and Donald Trump mentioned a plan to tackle egg prices in the State of the Union speech, putting his Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins on notice that she has to get the price down. Most notably, earlier this week, the Capitol Forum reported the Department of Justice Antitrust Division is now investigating egg markets. The reason is simple. For most Americans, eggs have always been cheap, and thus a key food staple. And now eggs are expensive, and sometimes in shortage. Over the past year egg prices have increased by 53%— jumping 15% in January alone. As of the beginning of February, egg producers were charging wholesale buyers an average of $5.95 for a dozen eggs, and retailers were charging consumers anywhere between $4 and $9 a dozen — and sometimes even more. The high prices, and sometimes shortages, are a problem in and of themselves, but they also represent that the American system has gone askew. If we can’t even get a cheap omelet or egg sandwich anymore, what can America do right? The stated reason for the high price of eggs is something that happens periodically: an avian flu epidemic. Since 2022, outbreaks of bird flu on poultry farms have led to the culling of over 115 million egg-laying hens. This epidemic, according to the prevailing narrative, has driven egg prices up to record highs all on its own. As one industry executive put it, it’s all just “supply disruption, ‘act of God’ type stuff.” The popular response to this story has been what you’d expect: Scientists are discussing flu vaccines for chickens, politicians are blaming each other about bird culls, and many are concerned about how the massive scale of today’s egg farms enables—and exacerbates—avian flu epidemics. And none of that is necessarily wrong. But something doesn’t add up about this “avian flu is the sole and natural cause of high egg prices” story. Despite the “act of God” going on — and the skyrocketing prices accompanying it — egg production is actually . . . not down by all that much. 115 million hens is a lot of birds to cull, but it’s important to put the loss of those hens in context: They weren’t lost all at once. They were lost over three years. And there have always been around 300 million other hens alive and kicking to lay eggs for America—not to mention a continuous pipeline of 120-130 million female chicks (called “pullets”) in the process of being raised into adult hens to replace the ones dying or aging out. As a result of this pipeline, the effect of avian flu outbreaks on egg production, while not insignificant, has been relatively small. Monthly egg production during each of the last three years has averaged only 3-5% lower than it was in 2021, the year before the epidemic started. Meanwhile, demand for eggs has actually declined. According to a private report by the Egg Industry Center, Americans went from consuming an average of 210 eggs each in 2021 to less than 190 in 2024 — a ~10-percent nosedive. As many countries have closed their markets to American eggs since 2021 on account of the avian flu, egg exports have also fallen off a cliff — going down by nearly half between 2021 and 2022 and staying there ever since. That dynamic, according to my analysis of USDA data, has shaved another ~2.5% off aggregate demand on U.S. egg production. So, reports of an unprecedented egg “shortage” are exaggerated. Nonetheless, egg prices — and egg company profits — have gone through the roof. Cal-Maine Foods — the largest egg producer and the only one that publishes its financial data as a publicly traded company — has been making more money than ever. It’s annual gross profits in the past three years have floated between3 and 6 timeswhat it used to earn before the avian flu epidemic started — breaking $1 billion for the first time in the company’s history. All of this extra profit is coming from higher selling prices, which have been earning Cal-Maine unprecedented 50-170 percent margins over farm production costs per dozen. Taking Cal-Maine as the “bellwether” for the industry’s largest firms — as people in the egg business do — we can be pretty confident that the other large egg producers are also raking in profits off the relatively small dip in egg production. High persistent profits are an anomaly for the industry. Historically, egg producers have responded to avian flu epidemics—and the temporary rise in egg prices that often accompanies them—by quickly rebuilding and expanding their flocks of egg-laying hens. “Fowl plagues”—as these epidemics used to be called—have been with us since at least the 19th century. Most recently, large-scale avian flu epidemics hit egg farms in 2015 and 1983-1984. The egg industry responded to both of these destructive events by sprinting to rebuild and expand the egg-laying hen flock — something which checked price increases and ultimately made sure prices went back to pre-epidemic levels within a reasonable time. As Cal-Maine Foods explained in its 2007 Annual Report: “In the past, during periods of high profitability, shell egg producers have tended to increase the number of layers in production with a resulting increase in the supply of shell eggs, which generally has caused a drop in shell egg prices until supply and demand return to balance.” For example, immediately after the height of the avian flu epidemic in May 2015, egg producers started adding millions more pullets to their operations each month—ultimately raising 15.3 million more pullets on their farms in 2015 than they did in 2014, and increasing that figure by another 8 million in 2016, according to my analysis of data from monthly USDA/NASS Chicken and Eggs reports. Altogether, producers added adult hens to their flocks at a prodigious rate of 4.15 million per month on average from July 2015 through February 2016, replacing nearly all of the hens lost to avian flu within 7 months. As a result, the average wholesale price of eggs landed at $1.65 a dozen that year, only 40 percent higher than it did the year before. By the end of March 2016, monthly egg production was higher than it was in March 2014 — and egg prices had not only returned to pre-epidemic levels, but were dropping even lower. This time around, however, that’s not happening. Despite high profits, the egg industry has somehow maintained a stubborn deficit in egg production capacity. Hatcheries — the firms that supply hens to egg producers — have throttled the pipeline of hens instead of expanding it. According to the Egg Industry Center, the size of the flock of “parent” hens — the hens used by hatcheries to produce layer chicks for egg producers — plummeted from 3.1 million hens in 2021, to 2.9 million in 2022, to 2.5 million hens in 2023 and 2024. Meanwhile, hatcheries have been hatching significantly fewer parent chicks to replace aging ones — nearly 380,000 (or 12 percent) fewer in 2022 compared to the year before, and even fewer parent chicks in 2023 and 2024 — leaving the parent flock older and more likely to produce eggs that fail to hatch. That could explain why, although hatcheries reported producing 125-200 million more fertilized eggs to the USDA in each of the last three years compared to 2021, the number of eggs they’ve placed in incubators and the number of chicks they’ve hatched from those eggs has either declined or stayed basically steady with 2021 levels in every year since.

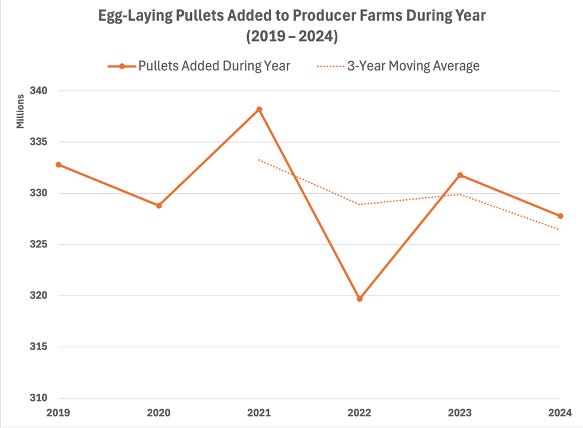

Chart by Basel Musharbash. Data Source: Egg Industry Center, U.S. Flock Trends and Projections (Feb. 6, 2025) (available from Egg Industry Center). As for egg producers themselves, you may be surprised to learn that they have added between 5 and 20 million fewer pullets to their farms in every one of the last three years than they did in 2021. As the USDA observed with some astonishment at the end of 2022, “producers—despite the record-high wholesale price [of eggs]—are taking a cautious approach to expanding production[.]” The following month, it pared down its table-egg production forecast for the entirety of 2023 on account of “the industry’s [persisting] cautious approach to expanding production.”

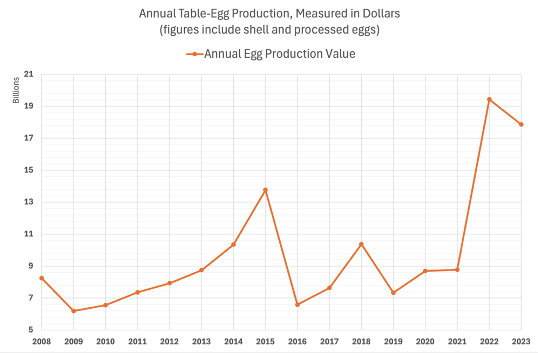

Chart developed from data compiled by Basel Musharbash from monthly USDA/NASS Chicken and Eggs reports for 2019-2024 period. In other words, the only thing that the egg industry seems to have expanded in response to the avian flu epidemic is windfall profits — which have likely amounted to more than $15 billion since the epidemic began (judging by the increase in the value of annual egg production since 2022), and appear to have been spent primarily on stock buybacks, dividends, and acquisitions of rivals instead of rebuilding and expanding flocks. When an industry starts profiting more from *not* producing than from producing, it’s a sign that something isn’t right. It could be an innocent bottleneck. But when it lasts for three years on end with no relief in sight, it’s usually a sign of something else that’s pervasive in America — monopolization.

As the coming installments in this series will detail, the fundamental problem in the egg supply chain today is the simple fact that every industry involved in turning an egg into a chicken and turning a chicken into an egg—from the breeders and hatcheries that create the hens to the producers who use the hens to make eggs—has been hijacked by one or two financier-backed corporations, with the incentives flipped from competing entities seeking to produce more eggs to an oligopoly trying to restrain the production of eggs. On one end of the egg supply chain, you have two companies who control chicken genetics, the billionaire-owned Erich Wesjohann Group and the private-equity-backed Hendrix Genetics. Headquartered a short car trip apart in Cuxhaven, Germany, and Boxmeer, Netherlands, these private firms have systematically gained control over the supply of egg-laying hens to American producers over the past two decades by buying out or suppressing rivals and challengers. Today, no egg producer in this country can expand the number of hens in its flock — or even replace the hens it already has when they age out or die — without the cooperation of this duopoly. And, since the value of hens rises with the price of the eggs, when the price of eggs is high these two barons have a clear interest in keeping the supply of pullets to producers on a tight leash — so the high prices stick. On the other end of the egg supply chain, you have the largest egg producer in the country and the world, Cal-Maine Foods.

Cal-Maine isn’t just the largest egg producer and distributor, but has a range of coercive tools at its disposal to discipline smaller rivals in the industry. Through what looks like a special arrangement with the chicken-genetics barons, Cal-Maine can expand its output faster and cheaper than any other egg producer. If a producer gets out of line and responds to high prices with flock expansions or discounting practices that Cal-Maine doesn’t approve of, Cal-Maine can flood the market with eggs—depressing prices for everyone while capturing market share for itself. As a publicly-traded company with a low cost of capital from Wall Street, Cal-Maine can live with low egg prices for a long time. Not so for most of the 60 or so family-owned producers who make up the rest of the egg industry; they’re actual businesses that need to turn a profit. The power wielded by these dominant firms — EW Group, Hendrix, and Cal-Maine — is not theoretical. Just last year, a federal jury found that, shortly after Cal-Maine rose to dominance in the late 1990s, its executives took over the leadership of a longstanding industry association called the United Egg Producers (UEP) and turned it into a cartel, the equivalent of what the presiding judge analogized to a “mob boss” for the industry. Shortly after, other major egg producers that had long resisted joining the UEP — like Rose Acre Farms — gave up their independence and entered the UEP’s fold, until it finally represented producers accounting for more than 90% of the country’s egg supply. Cal-Maine’s executives then used the association as a “bullhorn” to “bark out orders” at egg producers and “coordinate a conspiracy” to restrict the supply of eggs in the United States through a variety of strategies — including throttling the replacement of hens lost to mortality and a fake “animal welfare” program designed to reduce overall flock numbers rather than improve hen’s lives. An economist who helped plan the UEP cartel summed up the economic rationale behind it pretty simply: “More hens, less income!” And the conspiracy’s results proved he was right. Wholesale egg prices reached unprecedented heights over the course of the 2000s and then never came back down — settling around a new, higher focal point 50 to 100 percent higher than the pre-conspiracy level for the next decade. Something similar could be happening with the current avian flu epidemic. Indeed, the new focal point appears to be already here: There was an argument that wholesale egg prices “collapsed” in 2023. In reality, they were on average 75% higher than wholesale egg prices before the epidemic’s onset in 2022.

One way to understand the problem of eggs is consistent with similar problems we’re seeing in other parts of the economy. From baby formula to cancer drugs to beef, shortages and supply shocks in concentrated industries are now routine. In other words, the current egg crisis is what the Sovietization of American business looks like. We don’t have egg companies in the business of making eggs anymore. We have egg companies in the business of exploiting egg shortages, almost a private government of eggs. This dynamic is so extreme that the Agriculture Secretary had to go on something of a diplomatic mission to Cal-Maine last month to try to sweet-talk its executives into loosening their grip on the egg supply — and walked out of her meeting saying the USDA is going to pay egg producers to rebuild the country’s hen flockat a time when rebuilding the hen flock is going to be more profitable for them than it has ever been. So, that’s the broad-brush picture. To understand how we got to this place where shortages are more profitable than production, we have to start with the origins of the American egg business. After all, there’s a reason that a big cheap breakfast served in a diner on the roadside was such a big part of American culture, and why it’s such a shock to see Denny’s levy an egg surcharge. So let’s start with how the big fluffy omelet became so Americana. America as a Land of Egg Plenty Producing an egg seems simple. An “old McDonald had a farm” kind of farmer breeds a lovely hen, grows it to adulthood, has it lay eggs, puts those eggs in a crate, and sends that crate to a grocery store in return for a negotiated price. And that’s basically how the industry worked until the middle of the 20th century. The essentials of that story remained on point, but the components were split up among a series of specialized operations. If you abstract out what the egg farmer used to do all by himself, you get all the layers of the modern egg supply chain. First, as discussed above, there are breeders, who manage chicken genetics and produce “parent stock,” or the stock of birds that are mated to produce the fertilized eggs that become table-egg laying hens. Second, there are hatcheries, who buy parent stock from breeders, mate them to produce fertilized eggs, incubate their eggs to hatch table-egg laying chicks, and then grow the chicks into hens. Third, there are egg producers, who buy table-egg laying chicks or hens from the hatcheries and use them to produce eggs (some producers also buy fertilized eggs from hatcheries and incubate them in-house). Fourth, there are the various distributors and processors who buy eggs from producers. And finally, there are market makers who survey buyers and sellers for information about egg prices and other market data points, and use that information to publish regular benchmarks for the market value of eggs. So, to understand the story behind egg prices, we shouldn’t think about “the egg industry” or the “egg market” but a series of linked industries and markets — starting from the breeders and hatcheries, running through the egg producers and the egg buyers, all the way to the market makers — the end result of which is the carton of eggs on the shelf. To get there, we have to start eighty years ago, when egg production was revolutionized by new technologies and techniques, and the modern egg supply chain was born. In 1942, New Deal-era Secretary of Agriculture, and then Vice President, Henry A. Wallace built a new model for producing eggs. It was based on creating better birds through the “hybridization” of chicken, which is the crossing of two or more pure breeds of chicken to create a “hybrid” chicken with specific qualities. The resulting hens laid more or better eggs, required less feed, and were more adapted to specific production systems. After Wallace developed them, cross-breeding methods were shared with small breeders around the country through United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) extension offices at land grant colleges, which conducted basic research into the field and made breeding know-how and pure-bred stocks available to the public. Within a few years, dozens of other “primary breeders” emerged, creating a dynamic chicken genetics industry with many local and regional players.

In 1940, FDR named Henry A. Wallace his Vice President. This picture is from July 19th, 1940, during a White House broadcast about New Deal Farm Programs. These primary breeders developed branded strains of layer chickens and marketed them to thousands of hatcheries nationwide. The hatcheries bought “parent stock” for branded strains of chicken from the primary breeders, mated them to produce fertilized eggs, incubated the eggs until they hatched, and then sold the resulting chicks and young hens (called “pullets”) to farmers, which raised them into mature hens and then used them to produce eggs. As farmers got to know the different hybrid chicken brands, they selected among them for productivity and other characteristics that suited their production systems — creating a virtuous feedback loop. Soon, these developments led to a revolution in egg production both at home and around the world. The number of eggs laid per hen in the United States increased by almost 44% between 1940 and 1955 — more, in relative terms, than it would increase over the next four decades combined. Hybrid hens originating from the United States were soon introduced around the world, leading to a rapid expansion in global egg production—not to mention the explosion in cheap American diners dotting the new highway systems being built. In tandem with the mid-century revolution in chicken breeding, there was a revolution in egg production systems. Poultry science departments at land-grant colleges engaged in continual field testing and production research to develop new equipment and systems for egg farmers, ultimately developing critical technologies like large-scale incubators to hatch eggs on a schedule, fine-sand blowers to clean eggs without breaking shells, and caged-rearing systems to mechanize feeding, watering, and egg-collection in their hen houses. Although these innovations gave rise to some efficiencies of scale at the farm level and enabled the rise of factory-style hatcheries and egg production facilities, the industry as a whole remained highly decentralized at every stage of production and distribution well into the late 1970s. As late as 1978, most producers were still small, and most egg production still took place on farms with fewer than 50,000 hens. There were just 34 “big” egg companies with 1 million or more egg-laying hens each, and they accounted for only 27% of annual egg production. Undergirding this system was law: Antitrust enforcement prevented the largest breeders, hatcheries, and egg producers from growing by serial acquisitions or by handicapping their rivals’ access to customers or suppliers. For similar reasons, the markets into which egg producers sold their eggs—packers, retailers, processors, wholesalers, and institutions—also remained open and competitive, offering a wide diversity of potential buyers to egg producers of various sizes in every region of the country. Because of the openness of the egg industry and the abundance of small producers with excess capacity, there was almost always a significant surplus of eggs in the country. When that surplus narrowed (whether because of long-term population growth or a sudden crisis, like an avian flu epidemic), elevated egg prices invited rapid expansions in egg output from new and existing producers that quickly brought prices back down. For example, during the avian flu epidemic of 1983-1984, producers had to cull tens of millions of layer hens and other birds, including nearly every chicken in Pennsylvania. But retail egg prices rose by just 66 percent over a few months — and promptly fell just as sharply over the next few months as producers quickly replaced the hens they’d lost. “Eggs,” said a prominent agricultural economist in 1978, “will be processed and produced in this country if there is a fair return on investment. When the return [on eggs] becomes high,” he continued, “there will be expansion of production that will reduce prices.” And that was actually true: Higher prices routinely led farmers to get into the egg business to make money, and that in turn regularly reset the market with more supply. Price spikes were short-lived. Shortages were unheard of. America was a land of egg plenty. Then, everything changed. Stay tuned for part two of Hatching a Conspiracy, which will come next week. Hatching a Conspiracy is part of a new BIG project where we do deep investigative journalism on specific industries. If you’d like to support this work, sign up as a paid subscriber for BIG, or if you are already a paid subscriber, give a subscription to someone who you think would like it. Except where otherwise noted or linked, all statistical figures in Hatching a Conspiracy were derived by Basel Musharbash from analysis of data compiled from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service’s QuickStats database, Chicken and Eggs reports, and Hatchery Production Annual Summary reports, as well as the USDA Economic Research Service’s monthly international trade data hub. This is a free post of BIG by Matt Stoller. If you liked it, please sign up to support this newsletter so I can do in-depth writing that holds power to account. © 2025 Matt Stoller |