Bloomberg: America Is Drowning in Milk Nobody Wants

Dairy farmers are under siege thanks to low prices and changing tastes. Even a one-week holiday shutdown by yogurt giant Chobani inflicted pain.

by Deena Shanker and Lydia Mulvany | October 17, 2018

A decade ago, Greek yogurt was ascendant in America. In New York state, the hope among farmers and politicians was that their fortunes would benefit as well.

In 2005, Hamdi Ulukaya spent less than $1 million buying an old Kraft yogurt processing plant in New Berlin, 150 miles northwest of New York City. Within two years, the native of Turkey was already a success. His yogurt brand, Chobani, was in supermarket refrigerators everywhere, pushing aside older, big-name brands while making Greek yogurt a staple of the American diet. Rich but also healthy, it made its way into recipes for everything from smoothies to muffins and even popsicles.

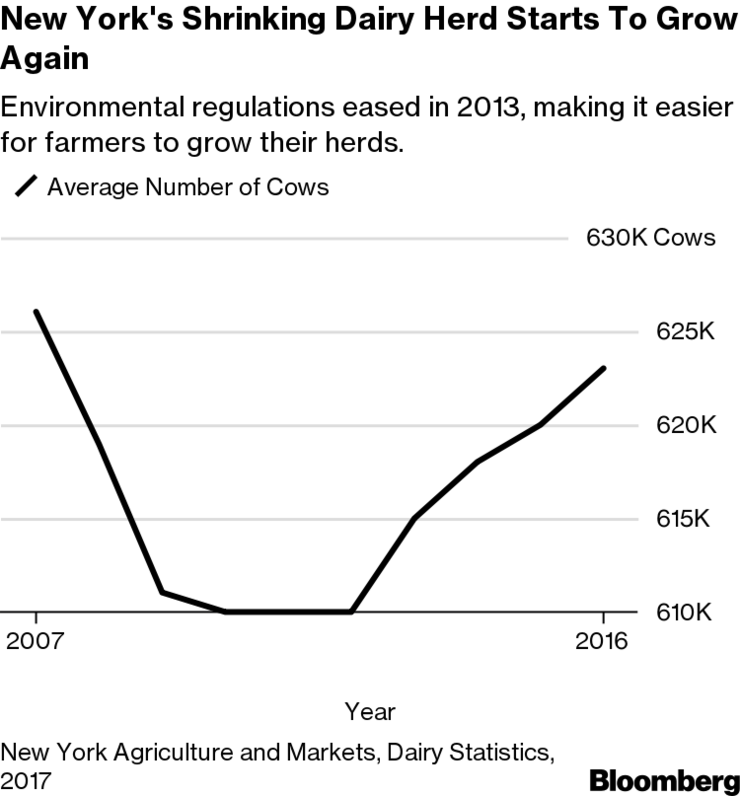

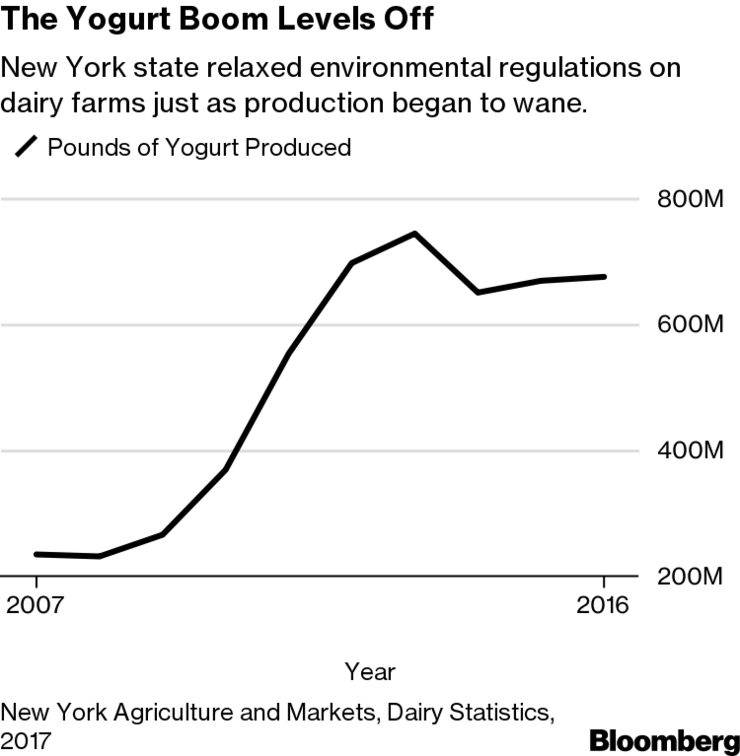

“Greek yogurt was a very big innovation in the yogurt market,” said Caleb Bryant, senior drink analyst at Mintel. For decades, yogurt was runny and high in sugar. “Then Chobani comes onto the scene and changes the idea of what yogurt can be.” With sales on the rise, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo convened the state’s first Yogurt Summit in 2012. In 2013, after the state became the top U.S. yogurt producer, he changed state law to allow farmers to have up to 299 cows instead of just 199 before they had to comply with certain environmental regulations.

The dairy industry in New York expanded rapidly. Yogurt production in the state peaked that year, tripling what it was in 2007.

But in the years that followed, Greek yogurt began to suffer the same fate that’s bedeviled the broader dairy industry—changing tastes.

From April 2017 to April 2018, sales of Chobani products grew only 1 percent while sales by all companies in the segment slipped 2.2 percent. Chobani’s growth is largely coming from Chobani Flip—a mixable yogurt product—and yogurt drinks, according to Bryant. (While the company’s New York facility still produces significantly more total yogurt, those products are both made in its Idaho plant.) Meanwhile, Chobani’s bonds are among the worst performers in the global food and beverage sector.

New York dairy farmers who jumped at the chance to expand their herds five years ago are now wondering whether it was the right move. “We were told we needed to expand,” said Deb Windecker, a dairy and beef farmer in the Mohawk Valley, and a former Chobani supplier. “ ‘Yogurt capital, grow, grow, grow.’ And now everybody’s turned their back on us.”

America’s dairy farmers face a growing list of challenges: The Trump administration’s trade wars have coincided with an extended period of already low milk prices. The strong dollar is driving down exports, and consolidation has led to farm closures all across the country. Most darkly, the long decline in American consumption of fluid milk, the dairy product that brings farmers the highest earnings, shows no sign of slowing.

The key ratio of income-to-feed costs reveals that dairy farmers have very little margin left these days, said Bill Brooks, an economist at INTL FCStone. Feed such as alfalfa and hay are more expensive than last year, as are labor and energy expenses.

With so little room to maneuver, even the smallest cutbacks can have a big effect. When Chobani closed its New York plant over the week of Fourth of July, around the same time a Kraft plant in nearby Walton, New York, did the same thing, it made the financial pain of its suppliers that much more acute.

“It was a tough deal for a lot of farmers,” said Richard A. Ball, commissioner of New York’s Department of Agriculture and Markets, emphasizing, however, that the global market forces share more of the blame for their plight.

For its part, Chobani (the name is derived from the Turkish word for “shepherd”) said it has gone “above and beyond” to mitigate the effects of the closing. It modified its plant so it could keep milk separators running during the closure, and over the course of the year it buys extra volume to make up for down periods. Moreover, the company said in a statement, its foundation has put millions of dollars into programs benefiting dairy communities. Even so, Dairy Farmers of America, the biggest dairy cooperative, said reductions in operating hours and scheduled plant shutdowns during the July Fourth holiday exacerbated the milk glut, and led them to dump some raw product on farms.

The amount of milk dumped by farmers in the U.S. Northeast reached almost 145 million pounds through July—the most in at least a decade—including 23.6 million pounds that month alone. Dairy co-ops will likely be forced to heavily discount milk prices in the coming months as a result, going below the current futures price for benchmark Class III milk, which goes into making cheese, and is currently under $16 per 100 pounds—a price that has farmers treading water, said Dave Kurzawski, a Chicago-based broker at INTL FCStone.

A worker inspects containers filled with Chobani yogurt at a facility in New Berlin, New York.

Photographer: Brady Dillsworth/Bloomberg

“The farmers, they don’t get a break,” he said. “We probably had a surplus of milk in this country for too long—we’re seeing that unwind itself.” And what can’t be sold—even at a discount—gets dumped. In recent years supplies have grown faster than manufacturing capacity, said Leon Berthiaume, chief executive officer of St. Alban’s Cooperative Creamery Inc. in Vermont. Discounts of $4 per 100 pounds wouldn’t be surprising for distressed milk, he said.

“We employ many tactics to find a home for our members’ milk, such as additional sales, drying, donating the milk or moving the milk to other areas where we can find demand,” said Nichole Wenderlich Owens, a spokeswoman for Dairy Farmers of America. “After exhausting all options, if an imbalance still exists, raw milk may be disposed.”

“When you have a free-market type of system, it just shows the vulnerability that the farm price has to market conditions,” said Doug DiMento, a spokesman for Agri-Mark. A cooperative that serves about 900 dairy farms in the Northeast, Agri-Mark recently invested $21 million to expand one of its four plants so it can take excess milk off the market.

Ball said the state is trying to address the declining fortunes of New York dairy farmers. This includes investing more than $250 million in expanded processing capacity, research at Cornell University on developing a milk-based recovery beverage for athletes, using milk to help feed the hungry and a marketing program to show consumers their milk is made locally.

“I don’t think we’ve exploited all the market share that we could,” Ball said.

Nevertheless, limiting supply—the ultimate solution to the glut—isn’t on the table. “Dairy farmers are free-market guys—they don’t want to be told how much to produce,” Ball said, even as supply management programs like those in Canada gain traction among U.S. farmers. For now, though, the state will stick to investing in ways to sell all this extra milk. “It’s a lot more fun to talk about how to increase demand than restrict what they’re doing.”

— With assistance by Craig Giammona