ABC News: Adelaide puts food, not developments at the top of the city-fringe menu

Photo: Scott Samwell’s family farm is one of Australia’s biggest brussels sprouts producers. (ABC News: David Sciasci)

by national rural and regional correspondent Dominique Schwartz | December 9, 2018

Scott Samwell lives on brussels sprouts.

His Adelaide Hills family is one of Australia’s biggest growers of the vegetable and the only producer of the kale-brussels sprout hybrid, the kalette.

Restaurant dishes such as twice-cooked brussels sprouts sautéed with bacon and sprinkled with parmesan have made the once-maligned vegetable hugely popular.

But the family is not able to expand its Mt Barker farm to keep up with demand because they would literally run into a brick wall.

“When we first came out to Bald Hills Road we were the only property out here, the only house out here,” Scott’s uncle Leigh Samwell said.

Thirty years on, “there are houses everywhere”.

Photo: Housing encroaches on farming property at Mount Barker in South Australia. (ABC News: David Sciasci)

Mount Barker is one of Australia’s fastest-growing urban centres.

Just half an hour’s drive from Adelaide by freeway, the once rural hamlet is now a satellite town of more than 35,000 people and is projected to grow 60 per cent within the next two decades.

Developers have offered the Samwells eye-watering sums of money for their land, but they have resisted selling.

And even if they wanted to cash in, from April next year they will not be allowed to sell to make way for housing.

South Australia appreciates the value of good food and wine

So much so, its city fringe farm land is being legally protected.

Agriculture is the state’s economic driver and a lot of it happens around the fertile fringe of Adelaide.

Two years ago, the then-state Labor government introduced Environment and Food Production Areas (EFPA) to restrict urban sprawl across a massive 8,000 square kilometres of land.

It’s illegal to subdivide rural land for residential housing within these protected areas.

The ban takes full effect in April 2019, and has the backing of the current Liberal government.

The Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale already have tough development restrictions in place.

Photo: The shaded areas show the Environment and Food Production Areas which restrict the development of new housing. (ABC News )

“It’s about protecting some of our best lands for food production,” South Australian Primary Industries Minister Tim Whetstone said.

“Horticulture is worth $22.5 billion and growing [and] peri-urban farms are critically important.”

What’s the main benefit of farming on the fringe?

In a word, water.

In Mount Barker, the Samwells might not be able to expand, but they do have ready access to three key ingredients often not available to farmers further afield.

- Labour

- Markets

- Recycled household waste water

That last one is especially important in Australia’s driest state.

During a drought, the rain may stop and rivers may dry, but people still wash, clean and flush.

Maybe not as much, but enough to guarantee an abundance of irrigation water for the Samwells, who are tapped into Mt Barker’s waste water treatment plant.

“We don’t want to have to grow in poor soil away from infrastructure, transport and water because it would increase the cost of what is already an expensive operation,” Scott Samwell said.

“So preserving what we have got close to cities and regional areas is important.”

Fringe farms serve up 80pc of Melbourne’s food

Dr Rachel Carey is a research fellow on sustainable food systems at Melbourne University and says we have “overlooked how important cities are for food production”.

She said Melbourne’s food bowl served up 80 per cent of the vegetables eaten by the city’s nearly 5 million residents.

In South Australia, the market gardens and orchards north of Adelaide alone account for one-fifth of the state’s horticulture.

Photo: The Adelaide Central Market sells fresh fruit and vegetables from the surrounding region. (ABC News: David Sciasci)

“It’s really important that all of Australia’s states now introduce much stronger protection for farmland on the city fringe,” she said.

Dr Carey said city fringe farms would become increasingly important as food supply was affected by climate change.

“We should see them as an insurance policy if you like, as a buffer against the future pressures and also potential shocks that we are likely to face to our food supply,” she said.

“We should be planning for at least 50 years and beyond in terms of saying there are areas that will not be touched for the long term, then the other crucial thing, of course, is to hold the line.”

Growers divided on food protection zones

“You can almost split my growers into two,” Jordan Brooke-Barnett, head of the SA branch of the grower association AusVeg, said.

Mr Brooke-Barnett said some AusVeg members were opposed to the development restrictions imposed by the EFPA.

“[They would] like the opportunity to subdivide land potentially one day to houses and the economic benefits that could potentially bring,” he said.

Others who deal with urban encroachment and “fight for the right to have their business exist” supported stronger protection of city fringe farms, according to Mr Brooke-Barnett.

In Queensland, fourth generation vegetable farmer Ray Taylor did move to a regional area, but he was happy to.

His family started farming just 11 kilometres from Brisbane’s CBD in 1914, but every generation was pushed further out as the city expanded.

Now, the Taylor’s main operation is near Stanthorpe, 225 km south-west of the capital.

“That enables us as a family to go and find a larger parcel of land in another area, so … obviously we can grow the business,” he said.

The Taylors grow 25 million vegetables per year, and while they can benefit from the economies of scale space brings, water security is a “massive issue”.

Photo: Ray Taylor at his farm near Stanthorpe in Queensland, where he has room to expand operations. (ABC News: David Sciasci)

Without rain, the farm’s 27 dams were only 20-60 per cent full and the main creeks had not run for 20 months, Mr Taylor said.

“We’re down about 30 per cent on [vegetable] production this year due to water scarceness.”

The family is planning to sell its last foothold on Brisbane’s urban fringe — a 40-acre waterfront property at Redland Bay.

“It’s too small … and you can’t expand it,” Mr Taylor said.

“We’re the last ones left there, so all the services have shut up and moved on and we get a lot of pressure from urban sprawl — spray drift, dust, noise — so it’s very difficult to operate in that environment.”

It is that situation South Australia is trying to avoid, according to the state’s Primary Industries Minister who makes no apologies for restricting urban sprawl.

“The government has to draw a line, [it has to] give a secure future to farmers and food production in South Australia, but also certainty to those developers looking to move into peri-urban areas of Adelaide and South Australia,” Mr Whetstone said.

SA plans $1 billion horticultural export hub on city fringe

The state is aiming is to ensure it has enough fresh produce not just to survive, but thrive.

Protecting farm land along the city edge is part of a greater plan to turn the Northern Adelaide Plains into an export hub and a global leader in intensive food production.

Work is underway to more than double the amount of treated waste water being piped to growers from Adelaide’s Bolivar waste water plant, and to open up new areas within the protected EFPA for irrigation.

The goal is to treble the value of northern Adelaide’s annual horticulture production to $1 billion within two decades and the plan has the backing of industry and all levels of government.

Providing certainty around land and water helped boost business confidence and available capital, Mr Whetstone said.

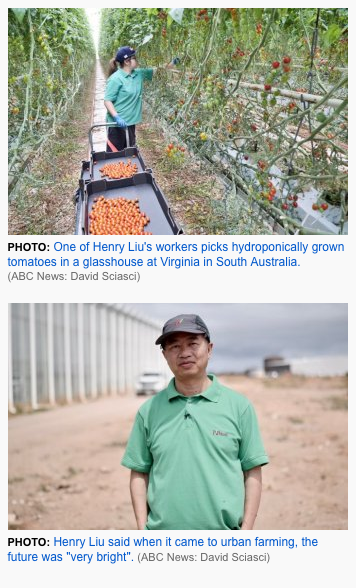

Meet investor Henry Liu

Henry Liu is one person investing heavily in South Australia’s food future.

Photo: Hydroponic vegetables growing in state-of-the-art, climate-controlled glasshouses. (ABC News: David Scaisci)

Mr Liu had one of the first greenhouses in Virginia north of Adelaide 18 years ago.

Mr Liu had one of the first greenhouses in Virginia north of Adelaide 18 years ago.

Now he has eight hectares of hydroponic vegetables growing in state-of-the-art, climate-controlled glasshouses.

That number will rise to 12 hectares when his new glasshouse starts production early next year.

“The future is great, very bright,” Mr Liu said.

Glasshouse crops use 95 per cent less water than those grown in the field and carbon dioxide can be captured and used to boost plant growth, he said.

“The advantage of glasshouses over field production is that you can control the growing conditions,” Mr Liu said.

But they are energy-hungry and solar power is not yet enough to run them.

Mr Liu believes hydroponic cropping will increase, but there will always be a place for soil-based growing and that however food is produced, being close to water, markets and labour is reason enough to protect city food bowls.