9.27.21 Omaha World Herald: The State of Beef: Producers ask Congress to increase competition among packers

The State of Beef: Producers ask Congress to increase competition among packers

· 9.27.21

· Omaha World Herald

Republican U.S. Sen. Deb Fischer on the ranch she owns with her husband, Bruce, near Valentine, Nebraska. A bill she authored would require meatpackers to acquire more of the cattle they slaughter through bidding on open livestock markets. “We need every segment of this industry to be able to succeed,. Fischer said. “Livestock is the economic drive of the state of Nebraska.”

DEB FISCHER

In a polarized U.S. Senate, Democrats Amy Klobuchar and Cory Booker seldom agree with Republicans Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley.

But all seemed to be on the same page during a recent hearing in Washington probing whether a lack of competition in the meatpacking industry has led to unfair prices for the nation’s cattle producers and excessive prices for beef consumers.

“We cannot have this level of concentration in this industry and have the farmer, the rancher paid less and less and less and the consumer charged more and more and more,” said Hawley, a Republican from Missouri. ”Something is seriously wrong here, and it cannot go on.”

New Jersey’s Booker agreed, saying the four big packers that control U.S. cattle slaughter have “gotten so large they now use their economic and political power to rig the entire system in their favor.”

Indeed, bipartisan support seems to be growing in Washington for measures seeking to beef up competition in the nation’s heavily concentrated meatpacking industry.

One of the primary proposals under discussion is a bill from Nebraska Republican Sen. Deb Fischer that would require packers to acquire more of the cattle they slaughter through bidding on open livestock markets.

“We need every segment of this industry to be able to succeed,” Fischer said. “Livestock is the economic driver of the state of Nebraska.”

ILLUSTRATION BY CHARLOTTE HIGGINS, THE WORLD-HERALD AND MATT HANEY, LEE ENTERPRISES

Separately, the Biden administration is also seeking to strengthen rules and ratchet up enforcement under a century-old law intended to level the playing field between producers and packers.

But such proposals face strong opposition from the packers. Industry officials argue that any such market interventions ignore the law of supply and demand and risk unintended consequences for producers, packers and consumers.

“This is a very competitive industry,” Tim Schellpeper, a beef executive for meatpacker JBS Foods who is from Stanton, Nebraska, testified in July before the Senate. “Margins do shift. Markets go in cycles.”

John Hansen, who for more than three decades has been lobbying federal agricultural policy as president of Nebraska Farmers Union, said he’s never before seen this kind of bipartisan momentum behind efforts to change the balance of power in cattle markets.

But he said nothing will be easy. The packers have proved a formidable political force in the past.

“The meatpackers do not want a fair, transparent, competitive and functional cattle marketing system,” Hansen said. “What they want is a cheap, dependable, controllable, low-cost raw material procurement system. And there is a fundamental difference between the two.”

ILLUSTRATION BY MATT HANEY

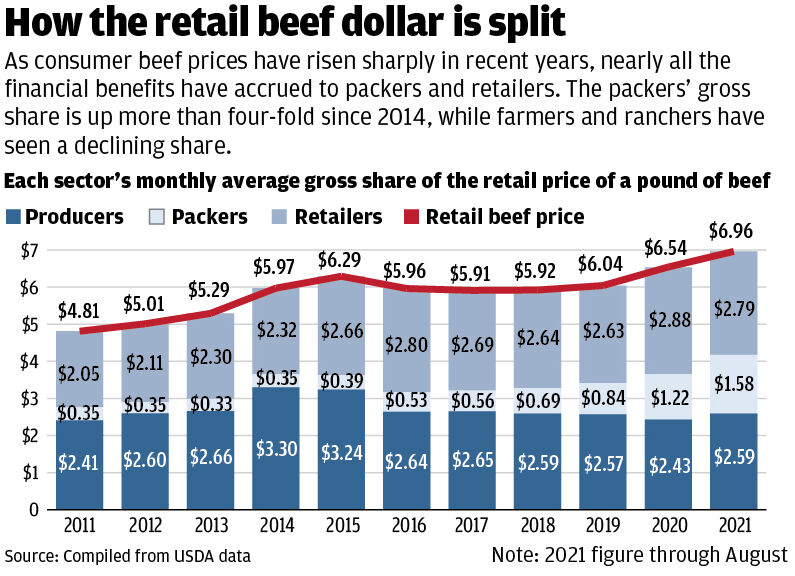

Current cattle prices are driving the issue. While consumers are paying record prices for beef at the grocery store, farmers and ranchers have endured years of declining prices for their cattle.

Many farmers and ranchers blame the market conditions on the extreme consolidation in the nation’s meatpacking industry. Today, some 85% of the fattened cattle that are turned into steaks and other choice cuts of meat in the United States are slaughtered by just four giant international processors.

Producers say industry consolidation has given packers the market power to manipulate the flow of cattle into the system, drive down cattle prices, fatten their profits and push up prices for consumers.

It’s clear that cattle producers now have the ear of Washington. The Senate held two hearings this summer exploring competition in cattle and beef markets, and there was one in the House, too.

During the hearings, lawmakers heard farmers and ranchers decry the lack of competitive bidding for their cattle, saying that frequently only one or two packers show up at auctions.

One reason for that is that packers today obtain only about a quarter of their cattle through such open markets. Instead, the vast majority are bought through marketing agreements with individual producers.

Such agreements aren’t publicly disclosed, reducing the ability of producers to know what a fair price is. The small number of cattle sold on open markets also tend to set the market price for all cattle, including those sold through marketing agreements.

Some producers say the lack of competitive bidders for their cattle can often leave them with little choice but to accept whatever price a packer is willing to pay.

“The price is dictated today, it’s not negotiated,” Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa said in a recent interview. “The cattlemen aren’t making any money, and the meatpackers are making this big profit.”

Grassley, a Republican farmer who during college worked as an administrator in a meatpacking plant, earlier this year introduced a bill requiring that a minimum of 50% of a packer’s weekly volume of cattle be purchased through bidding on the cash market.

Fischer, who has spent 40 years in ranching with her husband near Valentine, Nebraska, has introduced a bill with similar aims.

Rather than setting a universal 50% threshold for cattle bought through bidding, her “Cattle Market Transparency Act” would have the USDA set regional floors that would vary across the country.

That’s because the percentage of cattle sold at auction currently varies widely across the country. According to USDA figures, in Nebraska it’s about 41%, and in Iowa and Minnesota it’s 60%. But in the region that includes Texas and Oklahoma, it’s less than 10%.

- ILLUSTRATION BY MATT HANEY

“I think cash sales are important to know what the market price is,” Fischer said.

Fischer’s bill would also require the USDA to create and maintain a library of the marketing contracts between packers and producers, which would improve price transparency.

The Grassley and Fischer proposals came up during the recent hearings. While producers were supportive, some industry economists and analysts joined packers in expressing concerns.

Getting out more information can be helpful, said Kansas State economist Glynn Tonsor. But given the beef industry’s complexity, market interventions risk more harm than good.

“I don’t think it would be good for the industry, and I would discourage a politician from trying to narrow the margin for a sector,” he said in an interview.

Fischer and Grassley said they’re working closely together and hope to get a measure moving through Congress. With other provisions of the nation’s mandatory livestock price reporting system set to expire, they’re looking to leverage that deadline to pass provisions beefing up cash sales yet this year.

Grassley said it would be helpful if consumer groups would throw their support behind the legislation. They should be decrying the high prices being charged for beef at a time cattlemen aren’t making money, he said.

While President Joe Biden has expressed support, it would help if the president made clear to Democratic leadership in Congress that “I want to have this problem solved,” Grassley said.

“If the cattle feeders are getting screwed by the big packers, that ought to be high on the agenda of the leadership of the Ag Committee,” Grassley said.

Fischer said another barrier is the fact there isn’t always agreement among producers.

“We need the industry to come together, which is difficult,” she said. “These are rugged individualists.”

Even without legislative action, the Biden administration has announced a series of executive orders and initiatives it says would increase competition and make agriculture markets fairer for both producers and consumers.

One Biden executive order directs the USDA to consider new rules under the Packers and Stockyards Act to make it easier for farmers to bring and win claims against packers for unfair practices.

The Packers and Stockyards Act was passed by Congress in 1921 to protect poultry, hog and cattle farmers from unfair, deceptive and anti-competitive practices within meat markets.

But some producer groups say the act’s provisions have been watered down over time by court decisions and rule interpretations, shifting more power to packers. The packing industry is also more concentrated now than when the law was passed a century ago.

One proposed rule change would protect farmers from retaliation. Producers have expressed concerns that if they turn down packer bids, the buying representatives can retaliate by simply not showing up next time.

During a White House press briefing on the measures, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack recounted a recent conversation he had with a beef producer in Council Bluffs who said he was losing $150 on every head of cattle he sold, while seeing the packer make $1,800 after processing the same animal.

“Our job is to make sure that farmer gets a fair price and that when I go to the grocery store and I’m in the checkout line, I’m paying a fair price,” said Vilsack, a former Iowa governor.

Hansen warned that packers will fight hard against any changes. He noted that when Vilsack as President Barack Obama’s ag secretary similarly sought livestock rules changes, packers got a rider attached to a budget bill and defunded the effort.

“That’s raw political power,” Hansen said.

But with increased understanding of the problem and rising bipartisan support, Hansen said he’s cautiously optimistic something can be done this time.

“We have a set of opportunities and a variety of friends right now that we haven’t had for a very long time — maybe ever,” he said. “But we have to make a commitment that we will actually follow through. Because we are running out of time.”