Meatpacking workers, advocates describe ’dehumanizing’ conditions in Nebraska plants

Howdy,

Thanks to the Lincoln Journal Star and Jenna Thompson for an in depth look at Nebraska’ meatpacking industry through the eyes of meatpacking workers on this Labor Day weekend. I was unable to copy and paste two sets of graphs that dealt with worker injury rates. To get those, use the link below. Yours truly is quoted along with many others. Thanks to Nebraska Appleseed for their good work. Thanks to all the organizations that serve and advocate for our state’s “essential workers”. Thanks to all the workers who put their health and lives on the line for all of us. We owe you more than you will ever get paid.

All the best,

John K. Hansen, President

Nebraska Farmers Union

john

402-476-8815 Office 402-476-8859 Fax

402-476-8608 Home 402-580-8815 Cell

1305 Plum Street, Lincoln, NE 68502

Meatpacking workers, advocates describe ’dehumanizing’ conditions in Nebraska plants

Lincoln Journal Star

9.4.22·

· Before Guadalupe Vega Brown moved to Lincoln in 2018, she cut and packaged meat in different Nebraska plants.

Her work involved long days, physically demanding tasks and repetitive motions. After handling a knife for 10 hours, she’d come home tired and sore, pulling off her shoes with aching hands. It was hard work, she said — but that’s not what bothered her about her job.

Vega Brown said life in those steel, windowless plants is worse than she thinks most people know.

This summer, the Journal Star interviewed Vega Brown and five current workers from three different Nebraska meatpacking plants. Many utilized a translator. Pseudonyms of the five workers, who wished not to be named because they feared losing their jobs, are noted with asterisks.

Smithfield allowed the Journal Star to tour its Crete facility and held a roundtable discussion between the reporter and nine Smithfield employees — three corporate employees, the general and assistant manager, and several plant workers. The plant contributes to Nebraska’s multibillion dollar meat industry, processing about 1 million pounds of meat per day and feeding an estimated 30-40 million people every week.

Vega Brown and the anonymous meat processors were introduced to the Journal Star through Nebraska Appleseed, an organization that advocates for plant workers and connects with close to 600 meatpackers each year through safety seminars and community partners. The group has been in operation since 1996, helping educate workers about their rights and making the public aware of conditions inside meatpacking plants.

Each of the six meatpacking workers voiced concerns about frequent injuries, hazardous working conditions, discrimination and harassment in their workplace.

Darcy Tromanhauser, program director of immigrants and communities with Nebraska Appleseed, said their stories are common.

Darcy Tromanhauser

Courtesy photo

She believes the meatpacking industry stands in the way of a decades-long, hard-fought struggle for meatpacking workers’ rights.

“Over many years, so many workers have worked hard to tell this story,” Tromanhauser said. “And yet so many people are surprised to hear that this is going on.”

‘It’s constant injuries that we have to face’

Every day, around 26,600 Nebraska workers, many of whom are immigrants, head to work in meatpacking plants across the state. Vega Brown was one of them.

Work was fast, she said. The more tasks they could complete, the more money the company made. So, the conveyor belt flew.

She recalled a time on the line, frantically trying to manage the pork zipping by, when a sharp pain shot through her neck.

Guadalupe Vega Brown, a former meatpacking plant worker, shares her experience from years working on the line during an interview in early August. Vega Brown said life in those steel, windowless plants is worse than she thinks most people know.

KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Vega Brown screamed “Help me! I can’t move.” But her supervisor told her she needed to get back on the line.

“What are you doing? Get back to work!” Vega Brown said, imitating the woman with raised arms.

Vega Brown lay on the ground, writhing in pain, as work continued around her. A few coworkers who stopped to help were scolded by their supervisor. An ambulance was on its way, they were told. Nothing to see here.

“For me, that was the most dehumanizing thing that’s ever happened to me,” she said with tears in her eyes. “Sometimes I think I’ve moved past it, but knowing others are still going through the same thing makes it feel as if it’s just happened.”

Vega Brown was hospitalized for three days after her injury. Her plant had a penalty point system that allotted employees 15 points before termination. She received two penalty points for every day she was in the hospital.

When she argued that she shouldn’t have been penalized for being hospitalized, her bosses told her it didn’t matter. She wasn’t at work. Six points.

Andy* — a meatpacking worker who’s been employed in Nebraska for nearly two decades — said the industry takes advantage of immigrant employees like himself.

The white-coated workers with knives hurry to keep up, often at the expense of injuring themselves.

But Andy’s employers don’t like it when people complain.

“In my experience, when people get hurt, the company tries to terminate (them),” he said.

So, they stay on the line, keep quiet, and keep cutting. Even if it’s painful.

Workers handle pork at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Have things changed much since he first started? “No,” Andy said. “Not really.”

Is there one company that’s better to work for? “It’s all kinda the same,” he said.

Why doesn’t he complain? “HR doesn’t do anything.”

Andy said he feels stuck. Life in the plant is grim, but opportunities in rural Nebraska for people who don’t speak English fluently are few and far between. So, Andy and others keep working, hoping one day things will change.

In Sara’s* plant, she must finish more than six pieces per minute. The pressure to operate at a machine-like pace is painful, and the equipment she uses is old, unstable and unsafe, she said.

She wishes they could work at a more comfortable speed, but supervisors keep things moving, moving, moving, even when the plant is short on staff.

“It’s constant injuries that we have to face because of the conditions in the plant,” she said. “We all feel defeated, but because of the lack of workers we are expected to continue the same production value. If there are people with more time on their hands, they’re expected to work even harder, even though they are beating up their bodies to do it.”’

Tim* works at a different plant in Nebraska, but he also processes pigs.

On the kill floor, Tim said injuries are common. The mechanism that suspends the over 400-pound pigs by their hind feet is transporting them quickly and sometimes things go wrong, he said.

Nebraska meatpacking workers who spoke to the Journal Star said the pressure to operate at a machine-like pace on the production line often leads to injuries and chronic pain.

Courtesy photo, Nebraska Appleseed

He said he’s seen a couple of his coworkers being whisked away to the nurse after a pig fell on top of them.

Tim said that when injured workers are able, they keep working out of fear of retaliation, but others are taken to the nursing station.

“They’ll be given an ibuprofen or something for the pain, and they’ll just be taken back to the line,” he said.

Eric Reeder, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union in Omaha, said there are different line speed standards for industries depending on what the product is — line speed is measured differently for pork than it is for chicken, beef, etc. — but it’s easy for supervisors on the floor to turn the line speed up past a safe rate.

Eric Reeder

Courtesy photo

Furthermore, what constitutes a safe line speed depends on how many workers are on the line that day. This makes it hard for a standard speed to work well for every plant.

Reeder said he hears complaints of supervisors setting the line speed to an unworkable rate often. At times, plants exceed speeds agreed to by the union.

Smithfield, however, told the Journal Star in a written statement that it’s unlikely workers in their plants are sent back to the line after being injured. Such actions are against the company’s policy.

The company also denies ever going over maximum line speeds. It mentioned its opposition to a USDA-led pilot program to increase line speeds, stating it considers worker safety a priority.

“Line speeds at our harvest facilities never exceed the maximum USDA-approved rate of 1,106 head per hour,” the written statement read. “In fact, our line speeds often operate at significantly lower rates based on staffing levels at any given time.” ‘They can’t go to the bathroom, so they pee their pants’

Several workers told the Journal Star that, because of the plants’ urgency to keep the line moving, they’re frequently denied bathroom breaks by their employers.

Both Nebraska Appleseed and Reeder said they’ve also heard persistent complaints about lack of bathroom access from workers in Nebraska plants.

“They’re not letting me go to the bathroom,” Andy told the Journal Star. He recounted stories of his coworkers’ embarrassment after being unable to wait until the end of the day.

A supervisor told Andy’s team to wear diapers if they couldn’t “hold it.”

“A lot of people pee on the line,” he said. “They can’t go to the bathroom, so they pee their pants.”

Before Vega Brown could relieve herself, she’d have to ask a coworker to cover for her. If someone was able to take over her station, time spent on bathroom breaks was taken out of her lunch break.

But Smithfield’s Chief Administrative Officer Kiera Lombardo said employees in the company’s plants are free to relieve themselves whenever they need.

“Nobody is denied access to the restroom,” Lombardo said. “Ever.”

Victor* called working conditions in his plant “horrible” and said he had safety concerns.

A few months ago, Victor said, his plant had an ammonia leak from its refrigeration system, but his supervisors didn’t want to stop the line. Instead, employees continued to work while their bosses clamored to fix the issue.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, ammonia exposure can cause nausea, vomiting and burns to the respiratory tract.

“They didn’t sound the alarm,” Victor said.

‘Meatpacking companies are never going to make it to heaven’

According to the USDA, Nebraska led the nation in the number of cattle slaughtered in 2021 and ranks sixth in pork slaughter.

At the heart of this massive operation are people like Andy — immigrant workers trying to provide for their families.

Tromanhauser with Nebraska Appleseed said she’s heard alarming stories for years. Plants with poor working conditions thrive because workers feel powerless to improve their situation, she said.

“It’s an industry with extreme retaliation,” Tromanhauser said. “If people even try to just internally raise a safety concern, they’re told, ‘There’s the door if you want to leave.’”

Gloria Sarmiento, a community organizer with Nebraska Appleseed, said abuse in meat processing plants is an industry-wide issue.

Gloria Sarmiento

Courtesy photo

“Sometimes, when they are telling me a story, I want to cry with them,” Sarmiento said. “They complain from every company.”

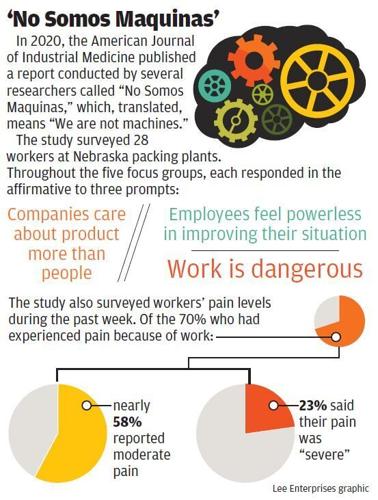

The Nebraska Farmers Union began to work with meatpacking employees after a 2020 investigation by Congress found that meatpacking companies ignored COVID-19 infections in order to continue operating. This, coupled with close quarters, led to widespread outbreak and death.

Since then, John Hansen, president of the Nebraska Farmers Union, has advocated for the proper care of workers.

John Hansen

Courtesy photo

Meatpacking plants’ misdeeds are two-fold, Hansen said. While their conditions hurt workers, packing plants also harm farmers. The companies’ non-competitive practices threaten smaller-scale operations, Hansen said, leading to more consolidation and fewer farmers.

According to the North American Meat Institute, the four largest companies conduct 70% of beef production.

“Based on how they treat workers, farmers and ranchers, I would say that there’s a very good chance that meatpacking companies are never going to make it to heaven,” Hansen said.

Reeder and the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which represents around 12,000 plant workers in Nebraska, strive to create fair contracts between the workers and employers.

Plant workers act as stewards and report to the union when there have been contract violations, such as line speeds, intimidation or abuse.

However, Reeder said, unionizing the plants is sometimes a challenge. Around 75% of plant members must be in favor of joining before the union will get involved, and there’s often pushback from plants once they hear whispers of unionizing.

A poster on COVID-19 prevention is seen at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

It’s not uncommon for plant heads to call meetings and tell workers not to speak with the union. They’ll threaten to close the plant if it becomes unionized, or they’ll misinform workers about the cost of union dues.

Reeder said some supervisors will tell workers that if they’re caught talking to the union, they’ll be fired, which is illegal. But many of the immigrant employees don’t know their rights and don’t always understand how unions could be beneficial, he said.

“Organizing a union gives you a voice and a sense of fairness in the workplace,” Reeder said. “The company would rather have the convenience to do what they want.”

Reeder said one of the most common issues the union faces between plants and workers is proper payment.

He hears complaints of workers not receiving correct payment several times a week. Reeder believes the companies take advantage of the fact that a large portion of its workforce might not speak English fluently.

“Figuring out if you are paid properly is difficult,” Reeder said. “If English is not your first language, it’s impossible.”

He said errors in payroll from plants across the state reach millions of dollars — and those are just from complaints union workers hear. Many won’t notice or say anything.

A stack of smoked pork is ready to be sliced into bacon at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Paul Doremus, general manager of Smithfield in Crete, said his facility has established a working relationship with the union.

“If we make a mistake, I want to make sure we correct it,” he said.

Jim Monroe, Smithfield’s vice president of corporate affairs, said the necessity of meat processing plants is often overlooked. Not only do they provide food to consumers all over the world, but they play a vital role in the economies of major farming and ranching states like Nebraska.

The Department of Homeland Security deemed meat processors essential workers during the pandemic.

“It’s one of the reasons we have so much gratitude for our team members,” Monroe said.

‘They yell at you like you’re an animal’

Each of the six workers from the state’s meatpacking industry the Journal Star spoke with mentioned being afraid of or intimidated by their supervisors.

Sara said her supervisors tend to yell, but the way her bosses treat workers sometimes depends on the employee’s ethnicity.

“My supervisor does have a lot of favoritism towards certain employees,” she said. “I know that certain supervisors get along better with people from (the U.S.), and not as much with the Hispanics.”

Carmen* said she reported a supervisor to HR, but she was told it was his word against hers.

“I’m scared to have these types of supervisors … because of the way they’re acting,” she said.

Carmen said some supervisors grope female employees. The workers who relent get certain benefits, like days off. In a separate interview, Sara said workers who have sexual relations with supervisors are favored.

Tromanhauser said she frequently hears allegations of sexual abuse in plants. Independently, Reeder also said he has heard complaints of women being sexually harassed.

Andy said his supervisors yell every day.

In fits of rage, supervisors have threatened Andy’s job and called him a “stupid Mexican.” They intimidate employees to complete tasks even if they’re unable.

“They yell at you like you’re an animal,” he said. “They think they are smart, and we are stupid because we use a knife.”

When workers at his plant try to complain about their bosses’ behavior, they’re asked to leave.

“It’s sad to see what’s going on,” he said. “If you try to go to HR, and say, ‘This supervisor intimidated and yelled at me,’ they’ll say, ‘Oh, you know what? You don’t want to work, so you get out of here.’”

Vega Brown said she felt some of her supervisors were racist.

“They’d say, ‘You wanted to work — work. You wanted to go north. This is the north. Work!’”

When the Occupational Safety and Health Administration comes for regular inspections — announced or not — Tim said conditions improve.

Supervisors are nicer and the line slows to a much more reasonable pace.

“Sometimes the supervisors know when OSHA is coming … So they try to make sure everything’s looking good,” he said. “Or if they can’t do it in time, they’ll just send everybody to break so that there’s no workers while OSHA’s walking around inspecting the plant.”

Workers handle pork at a meatpacking plant in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Lombardo with Smithfield believes the company differs from its competitors because of its culture. She said Smithfield goes out of its way to make sure employees feel valued and cared for, no matter their role.

“Our people really are everything to us,” she said. “They’re not a cost to us. They’re a value to us.”

‘We take seriously our role as an employer’

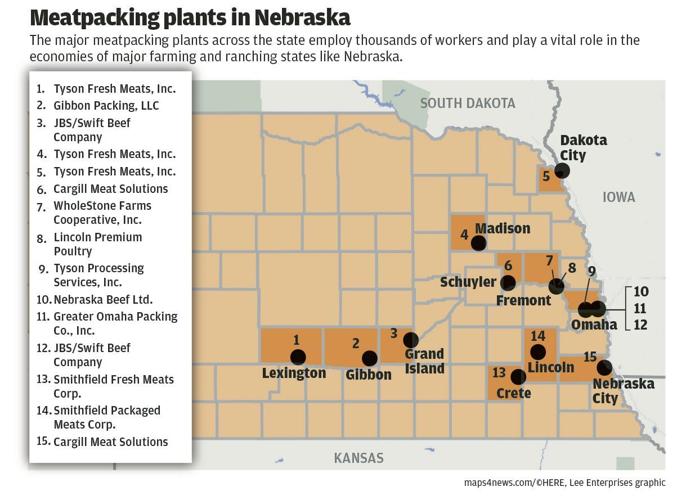

In Nebraska, the largest meatpacking companies are JBS, Cargill, Tyson and Smithfield.

In Smithfield’s Crete plant, roughly 70% of the nearly 1,500 employees are “white hat” processors, or non-lead, hands-on meatpackers. These workers have the same jobs as the six meatpackers the Journal Star spoke with at their respective plants.

A supervisor, line lead, production scheduler and quality control monitor at the Crete plant were at a roundtable employee discussion, and while no white hats were present, all attendees said they were heavily involved in line production.

Gary Fisher, an assistant general manager at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete, talks about the factory’s sausage production line during a tour in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Each employee at the discussion said they’d had a positive experience with the company. They had all been there for several years. Some, decades. Praises ranged from the familial atmosphere to the generous pay — meat processors at Smithfield start at $21.50 an hour.

Production supervisor Tyler Johnson said the company is extremely safety conscious, and it encourages workers to be in close communication with their bosses about potential concerns.

“I try to do my part to talk to every single person on my line, just to ensure that if something’s wrong or off, that they get the help that they need,” he said. “I stay in pretty good communication with my people.”

Lombardo said Smithfield instituted a “hands up” policy to ensure workers feel empowered to report potential issues or injuries. Raising a hand while on the line is meant to immediately alert supervisors to attend to a problem.

Additionally, she believes workers are well taken care of in every physical and emotional aspect.

The Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete contributes to Nebraska’s multibillion dollar meat industry, processing about 1 million pounds of meat per day and feeding an estimated 30-40 million people every week.

KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

On the tour, Smithfield representatives showed the Journal Star its various processing lines — nearly every station except the kill floor. Employees were told ahead of time that the Journal Star would be present, but general manager Doremus said the tour was a proper display of the plant’s daily activity.

Tyson Foods — which has plants in Omaha, Madison, Dakota City and Lexington — provided a written statement that said the company is committed to giving its workers the best environment possible.

“We take very seriously our role as an employer to a large and very diverse workforce and are committed to providing a safe and healthy workplace for all of our team members,” the statement read.

Tyson said it provides many avenues for workers to complain about mistreatment, such as Human Resources, its Employment Compliance Department, or the anonymous Tell Tyson First hotline.

Reeder said some of the companies have been responsive to complaints made through the union. But certain plants are more receptive than others, he said.

And while Reeder works to hold the companies accountable for their practices, it can be difficult for the higher-ups to get a full picture of what’s happening on the line all the time.

“The companies that have the most trouble are the larger factories,” Reeder said. “You’ve got a small HR team that is trying to manage the plant.”

In response to questions, Cargill provided a written statement. The company boasted of safety programs, like LIFESavers and Human and Organization Performance training, that contribute to the security of workers.

The smokehouse area at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete during a tour in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

“Our protein plants are operating in compliance with federal safety guidelines, and we work closely with state and local health authorities, as well as union representation, to make sure each plant meets the highest safety standards …” it read in part.

The company further maintained that its code of conduct prohibits any worker mistreatment, and potential misconduct is handled “promptly, fairly and as confidentially as possible.”

JBS, too, provided a written response to the Journal Star’s list of questions. The company statement said its Ethics and Compliance department investigates all allegations and takes the necessary steps to remedy issues.

“We have zero tolerance for abuse, discrimination, intimidation or mistreatment of our team members, and action should be taken immediately if any of these things takes place in our facilities,” the statement read.

‘Please, can you help us?’

Some meatpacking workers have hope that things could improve, but others aren’t so sure.

“Unless somebody from the outside is willing to help, I don’t see it getting better,” Victor said.

Andy said he’s not sure if things will improve either. Throughout the many years he’s been a meat processor, things have stayed more or less the same.

A worker processes pork loin on the packaging line at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Crete in August.

JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

But he still hopes legislators will pay attention to the industry’s issues.

“Please, can you help us? Can you make some laws to protect us?” he said.

Andy said he felt it was most important for the line speeds to be slowed down. He finds it sometimes impossible to work at the pace his employer requires.

In 1999, former Gov. Mike Johanns created a meatpacking workers’ bill of rights after reading stories published in the Journal Star detailing the plight of employees, but Tromanhauser doesn’t believe much has changed since then.

For now, Carmen, Victor, Andy, Sara and Tim continue to work in what they describe as poor conditions. Vega Brown has moved on from her former employer, but she still struggles with chronic pain as a result of the physical stress she once put on her body.

By speaking out, Andy said he hopes his fellow Nebraskans will begin to understand the challenges he experiences, all to put food on their tables.

“How can we sacrifice people to make all this food?”

Carmen and Victor were interviewed with the help of family members, who assisted with translation. Sara utilized the translation skills of Ruby Mendez Lopez, a bilingual employee with Nebraska Appleseed. Journal Star reporter Evelyn Mejia assisted with the translation of Vega Brown’s interview.