26 September, 2021 10:05

Supply and demand or meatpacker consolidation — who is right in beef over beef?

· 9.26.21

· Omaha World Herald

·

· On a recent “Feeder Flash,” a daily video on cattle markets produced for a Nebraska auction house, commentator Corbitt Wall noted that the major meatpackers were bidding on very few cattle across Kansas that week.

The packers, he said, were refusing to pay the going rate of $130 per hundredweight.

“Your major packers are resisting the 130, they put their foot down, they won’t give it, and they’re trying to get something bought significantly lower than that,” Wall said.

Wall bluntly offered that as long as ranchers have to sell their animals in markets with little competition or negotiation, “this feeding cattle sector is screwed.”

Wall isn’t the only one who believes a lack of packer competition has created an imbalance of power in the nation’s cattle markets that threatens producers.

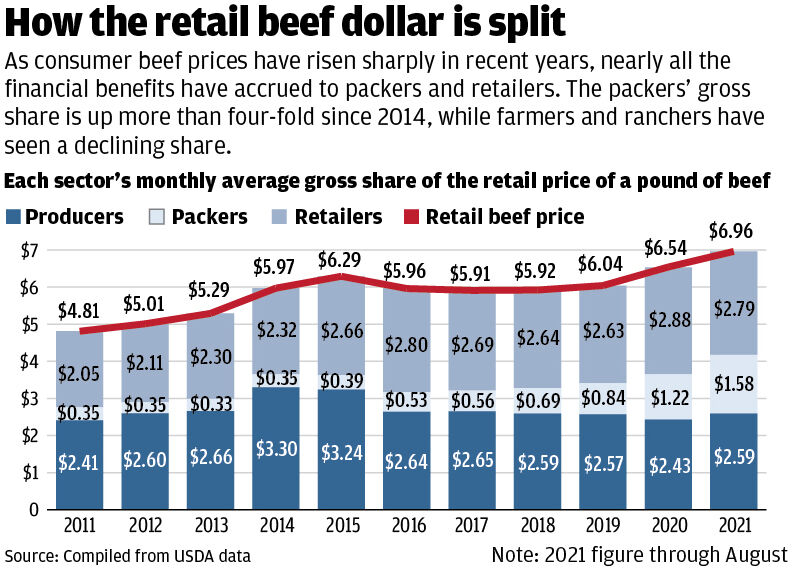

At a time of record consumer prices for beef, farmers and ranchers have endured years of declining prices for their cattle. Meanwhile, the four big packers, who control 85% of the market for fattened cattle, have seen their share of the beef dollar skyrocket.

Overall, industry observers are split on whether consolidation in the packing industry is to blame for current market conditions.

Take a look at the major players in the beef industry and how the beef on your table got from pasture to plate.

Most university economists and analysts who follow the industry say they see nothing fundamentally wrong. They trace the current conditions to an oversupply of cattle, a loss of animal-processing capacity due to plant closures, COVID-19 disruptions and recent labor shortages.

“We have had more cattle than we’ve had the ability to comfortably process,” said Glynn Tonsor, a beef industry economist from Kansas State University. “That’s a new development in the history of the industry."

But experts in antitrust law say they’re not so sure anti-competitive behavior among packers can be ruled out.

Diana Moss, president of the American Antitrust Institute, called the increase in the packers’ share of the beef dollar “oddly high,” and it continues to rise this year.

“It’s concerning,” said Moss, who is also an economist. “There are more predictable market dynamics, and then there is the exercise of market power by powerful market players. You can’t rule out the role of anti-competitive pricing.”

Deepening suspicion among producers is the fact that JBS and Tyson, two of the Big Four beef packers, have recently agreed to pay hundreds of millions in penalties and civil settlements amid price-fixing allegations within the chicken industry. JBS also settled pork price-fixing litigation.

If such anti-competitive behavior has been found within other meat industries, could it be happening in beef?

It appears the Justice Department’s antitrust division may be attempting to find out. According to published reports, investigators a year ago issued civil subpoenas to the Big Four.

Several producers, including a large feedlot owner from Nebraska’s Panhandle, have also filed a federal civil case charging price-fixing in beef.

Beef industry academic economists and analysts acknowledge the widened divide between cattle and beef prices. But they say to fully understand what’s happened, you need to go back to the first decade of this century.

Due to severe drought that limited available pasture lands, Tonsor said, producers reduced their cow herds. USDA figures show the total number of cattle dropped from nearly 97 million in 2007 to 88 million by 2014.

With packers competing for significantly fewer cattle, they bid up the price to levels many producers never thought they would see, Tonsor said. Those were very good years for producers.

But those cattle prices were also at levels where many plants were not profitable, said Dustin Aherin, who analyzes the beef industry for ag lender Rabobank.

As a result, the most inefficient plants were driven out of business. Between 2000 and 2015, the industry saw a 12% drop in slaughter capacity.

Then when producers post-drought built the national herd back, plant capacity was down. Tonsor and Aherin said that by 2016, it appears the number of cattle exceeded slaughter capacity — possibly for the first time in history.

Then throw in a fire that idled a large Kansas plant in 2019 and production disruptions due to COVID-19, which Aherin said “came at the worst possible time for the industry.”

All in all, Aherin said, movements in cattle and beef prices “have fallen within the ballpark of expectations. That doesn’t make it any less challenging (for producers).”

Tonsor and Aherin acknowledged that the market changes also left the packers strategically positioned to capture record shares of the beef dollar. Aherin noted that’s coming on the heels of a years-long period when many plants on net lost money.

Tonsor traced the current unrest among producers to “jealousy” over how the beef dollar is being divided among the sectors.

“I don’t think it’s my job to say (profit) is too high,” he said.

Beef economists from Iowa State, California-Davis and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln also said they believe current market conditions can be explained. UNL’s Elliott Dennis said more than a century of history has shown that each time the nation’s cattlemen have faced tough economic times, they have tended to point the finger at packers and consolidation.

"Are (packer) spreads high? Yes," Dennis said. "Can we explain why spreads are high in an economically sound manner? Yes."

Moss, the antitrust expert, said she’s not surprised that industry economists would defend the status quo. Many may focus narrowly on supply and demand factors rather than consider the role of market power.

And while cattle markets indeed are heavily influenced by cattle numbers, Moss said, that does not mean that’s the sole driver of cattle and beef prices.

She noted that both the packer and retail sectors have seen their share of the beef dollar grow significantly since 1980, corresponding with a period that saw major mergers and massive consolidation in both sectors.

Between 1980 and 2020, the retail sector’s percentage of the beef dollar has grown about 65%, while the packer share has increased even more, by over 70%. At the same time, producers’ share fell by more than 40%.

ILLUSTRATION BY MATT HANEY

“A picture is worth a thousand words,” Moss said. “In this time of increasing margins, consolidation has been rampant.”

George Slover, a former Justice Department antitrust lawyer who now serves as senior policy counsel for Consumer Reports, agreed something besides simple supply and demand seems to be at work.

“Concentration is the most obvious choice for what that could be,” he said.

With so few packinghouse representatives competing for feedlot cattle, Slover said they don’t have to meet in a smoke-filled room to coordinate on pricing. They just need to “stay out of each other’s way.”

“When you are just bidding against one other packer and it’s a guy you see all the time, the tendency is to relax a bit and say he’ll get them at this place, I’ll get them at another place, and it will all work out,” Slover said.

The Justice Department investigation suggests regulators are looking into the possibility that market players have directly conspired to fix prices in beef. And there’s already legal evidence there has been anti-competitive behavior within other meat markets.

In February, the Justice Department announced that a Colorado-based affiliate of JBS had pleaded guilty of conspiring to fix prices and rig bids in the broiler chicken industry. Pilgrim’s Pride agreed to pay $107 million in criminal fines, and also paid $75 million to settle civil litigation.

When Tyson was subpoenaed as part of the chicken litigation, the company revealed to authorities it had uncovered "internal issues" of concern. It made application under a federal program that provides leniency for companies cooperating in cartel investigations and also agreed to pay $222 million to settle civil litigation.

JBS in the past year also has agreed to more than $50 million to settle price-fixing lawsuits in the pork industry. Most of the meatpacking litigation alleges the major industry players worked through an outside agricultural data company to exchange critical pricing information.

JBS’s Brazilian parent company a year ago also pleaded guilty to U.S. charges that it had paid $150 million in bribes to Brazilian officials to advance its global business interests. The company agreed to pay $128 million in criminal fines.

The packing industry has consistently argued that recent price changes for cattle and beef have been simply a result of supply and demand.

Despite requests for updates from a number of elected officials, including Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, Justice Department officials have not commented publicly on the status of the current beef probe.

“Producers and consumers deserve fairness and transparency now more than ever,” Ricketts and five other beef state governors wrote.