WSJ: Rural America Is the New ‘Inner City’

By Janet Adamy and Paul Overberg

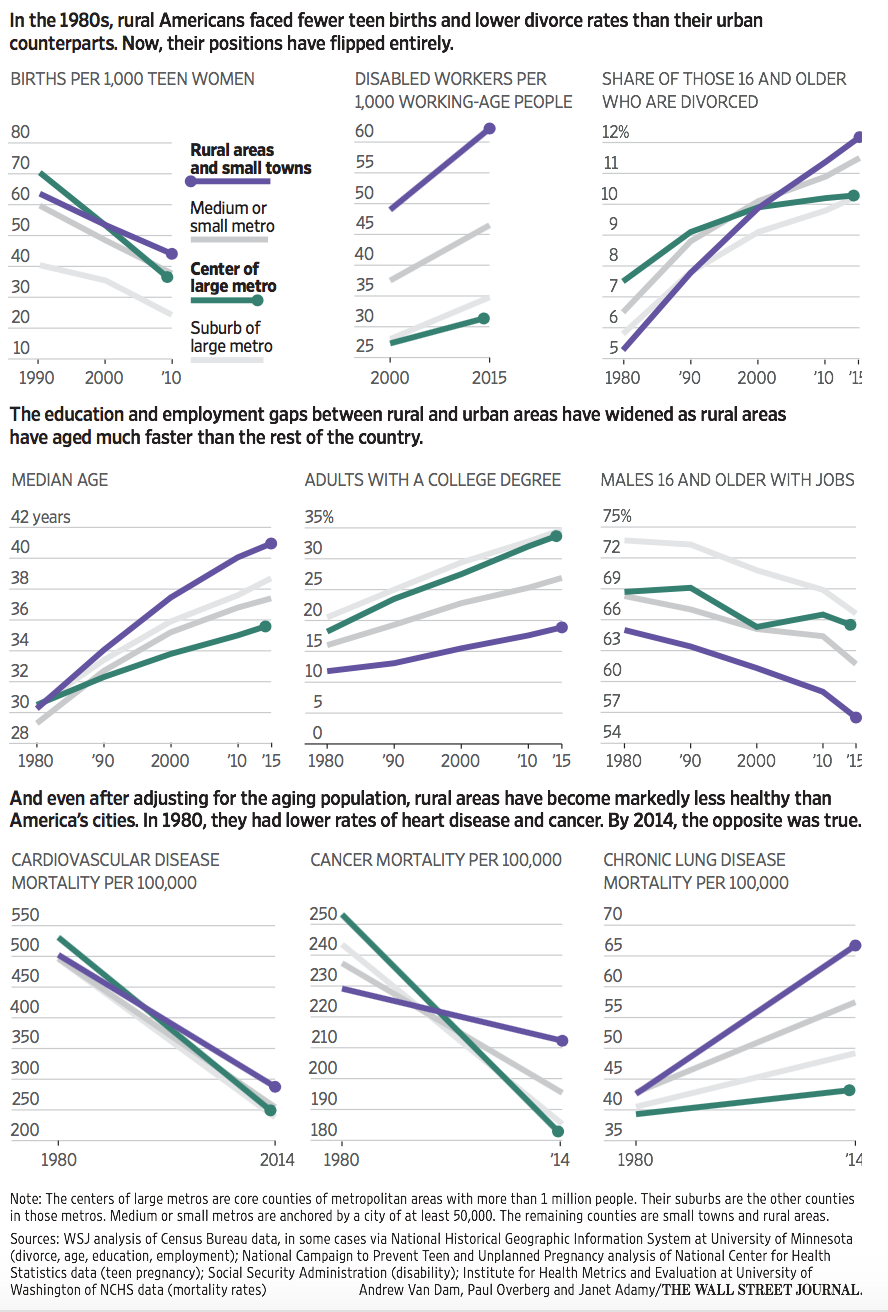

A Wall Street Journal analysis shows that since the 1990s, sparsely populated counties have replaced large cities as America’s most troubled areas by key measures of socioeconomic well-being—a decline that’s accelerating

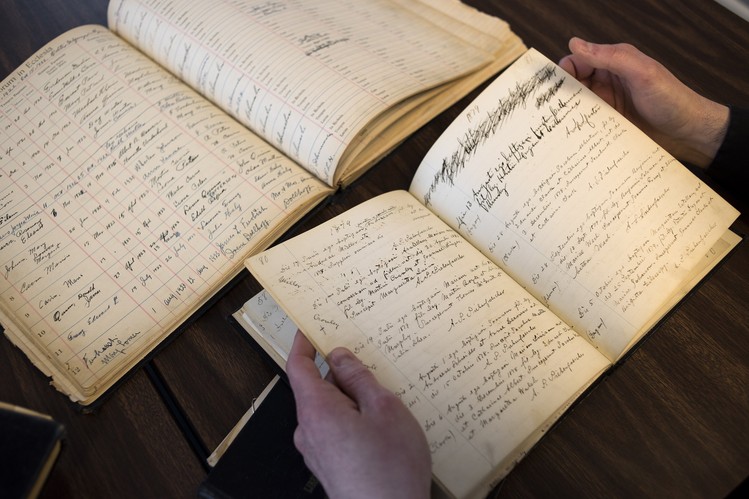

At the corner where East North Street meets North Cherry Street in the small Ohio town of Kenton, the Immaculate Conception Church keeps a handwritten record of major ceremonies. Over the last decade, according to these sacramental registries, the church has held twice as many funerals as baptisms.

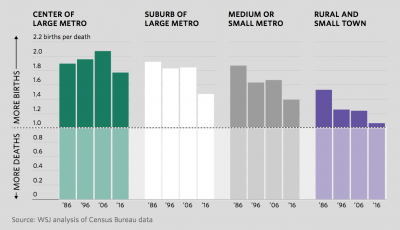

In tiny communities like Kenton, an unprecedented shift is under way. Federal and other data show that in 2013, in the majority of sparsely populated U.S. counties, more people died than were born—the first time that’s happened since the dawn of universal birth registration in the 1930s.

The Rev. Dave Young examines baptismal records at Immaculate Conception Church in Kenton, Ohio. Over the last decade, the church has hosted more funerals than baptisms. Photo: Ty Wright for The Wall Street Journal

For more than a century, rural towns sustained themselves, and often thrived, through a mix of agriculture and light manufacturing. Until recently, programs funded by counties and townships, combined with the charitable efforts of churches and community groups, provided a viable social safety net in lean times.

Starting in the 1980s, the nation’s basket cases were its urban areas—where a toxic stew of crime, drugs and suburban flight conspired to make large cities the slowest-growing and most troubled places.

Today, however, a Wall Street Journal analysis shows that by many key measures of socioeconomic well-being, those charts have flipped. In terms of poverty, college attainment, teenage births, divorce, death rates from heart disease and cancer, reliance on federal disability insurance and male labor-force participation, rural counties now rank the worst among the four major U.S. population groupings (the others are big cities, suburbs and medium or small metro areas).

In fact, the total rural population—accounting for births, deaths and migration—has declined for five straight years.

From Breadbasket to Basket Case

“The gap is opening up and will continue to open up,” said Enrico Moretti, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied the new urban-rural divide.

Just two decades ago, the onset of new technologies, in particular the internet, promised to boost the fortunes of rural areas by allowing more people to work from anywhere and freeing companies to expand and invest outside metropolitan areas. Those gains never materialized.

As jobs in manufacturing and agriculture continue to vanish, America’s heartland faces a larger, more existential crisis. Some economists now believe that a modern nation is richer when economic activity is concentrated in cities.

Downtown storefronts in Kenton, Ohio, population 8,200. The poverty rate in Hardin County has risen by 45% since 1980 Photo: Ty Wright for The Wall Street Journal

In Hardin County, where Kenton is the seat, factories that once made cabooses for trains and axles for commercial trucks have shut down. Since 1980, the share of county residents who live in poverty has risen by 45% and median household income adjusted for inflation has fallen by 7%.

At the same time, census figures show, the percentage of adults who are divorced has nearly tripled, outpacing the U.S. average. Opioid abuse is also driving up crime.

Father Dave Young, the 38-year-old Catholic priest at Immaculate Conception, was shocked when a thief stole ornamental candlesticks and a ciborium, spilling communion wafers along the way.

Father Young at prayer in the pews at Immaculate Conception Church. Photo: Ty Wright for The Wall Street Journal

Before coming to this county a decade ago, Father Young had grown up in nearby Columbus—where for many years he didn’t feel safe walking the streets. “I always had my guard up,” he said.

Since 1980, however, the state capital’s population has risen 52%, buoyed by thousands of jobs from J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., plus the growth of Ohio State University. Median household income in Columbus is up 6% over the same span, adjusted for inflation. “The economy has grown a lot there,” said Father Young. “The downtown, they’ve really worked on it.”

Meanwhile, as Kenton—population 8,200—continues to unravel, he said he has begun always locking the church door. Again, he finds himself looking over his shoulder.

“I just did not expect it here,” he said.

In the first half of the 20th century, America’s cities grew into booming hubs for heavy manufacturing, expanding at a prodigious clip. By the 1960s, however, cheap land in the suburbs and generous highway and mortgage subsidies provided city dwellers with a ready escape—just as racial tensions prompted many white residents to leave.

Gutted neighborhoods and the loss of jobs and taxpayers contributed to a socioeconomic collapse. From the 1980s into the mid-1990s, the data show, America’s big cities had the highest concentration of divorced people and the highest rates of teenage births and deaths from cardiovascular disease and cancer. “The whole narrative was ‘the urban crisis,’” said Henry Cisneros, who was Bill Clinton’s secretary of housing and urban development.

To address these problems, the Clinton administration pursued aggressive new policies to target urban ills. Public-housing projects were demolished to break up pockets of concentrated poverty that had incubated crime and the crack cocaine epidemic.

At that time, rural America seemed stable by comparison—if not prosperous. Well into the mid-1990s, the nation’s smallest counties were home to almost one-third of all net new business establishments, more than twice the share spawned in the largest counties, according to the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan public-policy organization. Employers offering private health insurance propped up medical centers that gave rural residents access to reliable care.

Hitting the Floor

Rural America is getting perilously close to the milestone at which more people are dying than are being born.

By the late 1990s, the shift to a knowledge-based economy began transforming cities into magnets for desirable high-wage jobs. For a new generation of workers raised in suburbs, or arriving from other countries, cities offered diversity and density that bolstered opportunities for work and play. Urban residents who owned their homes saw rapid price appreciation, while many low-wage earners were driven to city fringes.

As crime rates fell, urban developers sought to cater to a new upper-middle class. Hospital systems invested in sophisticated heart-attack and stroke-treatment protocols to make common medical problems less deadly. Campaigns to combat teenage pregnancy favored cities where they could reach more people.

As large cities and suburbs and midsize metros saw an upswing in key measures of quality of life, rural areas struggled to find ways to harness the changing economy.

The Perkins building, at right, in downtown Coffeyville, Kan. It was home to a bank the Dalton Gang attempted to rob in 1892. Photo: Nick Schnelle for The Wall Street Journal

Starting in the late 1990s, Amazon.com Inc. began opening fulfillment centers in sparsely populated states to help customers avoid sales taxes. One of those centers, established in 1999, brought hundreds of jobs to Coffeyville, Kan.—population 9,500.

Yet as two-day shipping became a priority, Amazon shifted its warehousing strategy to be closer to cities where its customers were concentrated, and shut the Coffeyville center in 2015.

An Amazon spokeswoman said that it didn’t make the decision lightly, and that last year it opened one of two planned fulfillment centers near Kansas City that will create more than 2,000 full-time jobs.

Just as Amazon closed down, so did the century-old hospital in nearby Independence, population 8,700.

The nearly one-million-square-foot Coffeyville warehouse Amazon rented has been empty since it went on the market for $35 million, and was recently repossessed at a value of $11.4 million after the building owner filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

The former Amazon.com Inc. fulfillment center in Coffeyville, Kan. The building has been empty since the company left in 2015. Photo: Nick Schnelle for The Wall Street Journal

Coffeyville officials said the area’s problem isn’t a lack of jobs—it’s a shortage of qualified workers. After Amazon said it would close, economic-development leaders held an employment fair expecting to get up to 600 job seekers. Fewer than 100 showed up, said Trisha Purdon, executive director of the Montgomery County Action Council.

In the late 1990s, convinced that technology would allow companies to shift back-office jobs to small towns, former Utah Republican Gov. Mike Leavitt pitched outposts in his state to potential employers. But companies were turned off by the idea of having to visit and maintain offices in such locations, he said. Eventually, many of the call centers he landed moved overseas where labor was even cheaper.

Although federal and state antipoverty programs were not limited to urban areas, they often failed to address the realities of the rural poor. The 1996 welfare overhaul put more city dwellers back to work, for example, but didn’t take into account the lack of public transportation and child care that made it difficult for people in small towns to hold down jobs, said Lisa Pruitt, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law.

Rhonda Vannoster of Independence, Kan., looks after her 11-month-old daughter Róisin McCoy. She does not own a car and has struggled to find a job. Photo: Nick Schnelle for The Wall Street Journal

Rhonda Vannoster of Independence, Kan., who is 25, has four children with a fifth on the way. She is divorced and jobless and doesn’t own a car, which limits her work options. She said she wants to get trained as a nursing aide but struggles to make time for it. “There just aren’t a lot of good jobs,” she said.

There has long been a wage gap between workers in urban and rural areas, but the recession of 2007-09 caused it to widen. In densely populated labor markets (with more than one million workers), Prof. Moretti found that the average wage is now one-third higher than in less-populated places that have 250,000 or fewer workers—a difference 50% larger than it was in the 1970s.

As employers left small towns, many of the most ambitious young residents packed up and left, too. In 1980, the median age of people in small towns and big cities almost matched. Today, the median age in small towns is about 41 years—five years above the median in big cities. A third of adults in urban areas hold a college degree, almost twice the share in rural counties, census figures show.

Consolidation has shut down many rural hospitals, which have struggled from a shortage of patients with employer-sponsored insurance. At least 79 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Rural residents say irregular care and long drives for treatment left them sicker, a shift made worse by high rates of rural obesity and smoking. “Once you have a cancer diagnosis…your probability of survival is much lower in rural areas,” said Gopal K. Singh, a senior federal health agency research analyst who has studied mortality differences.

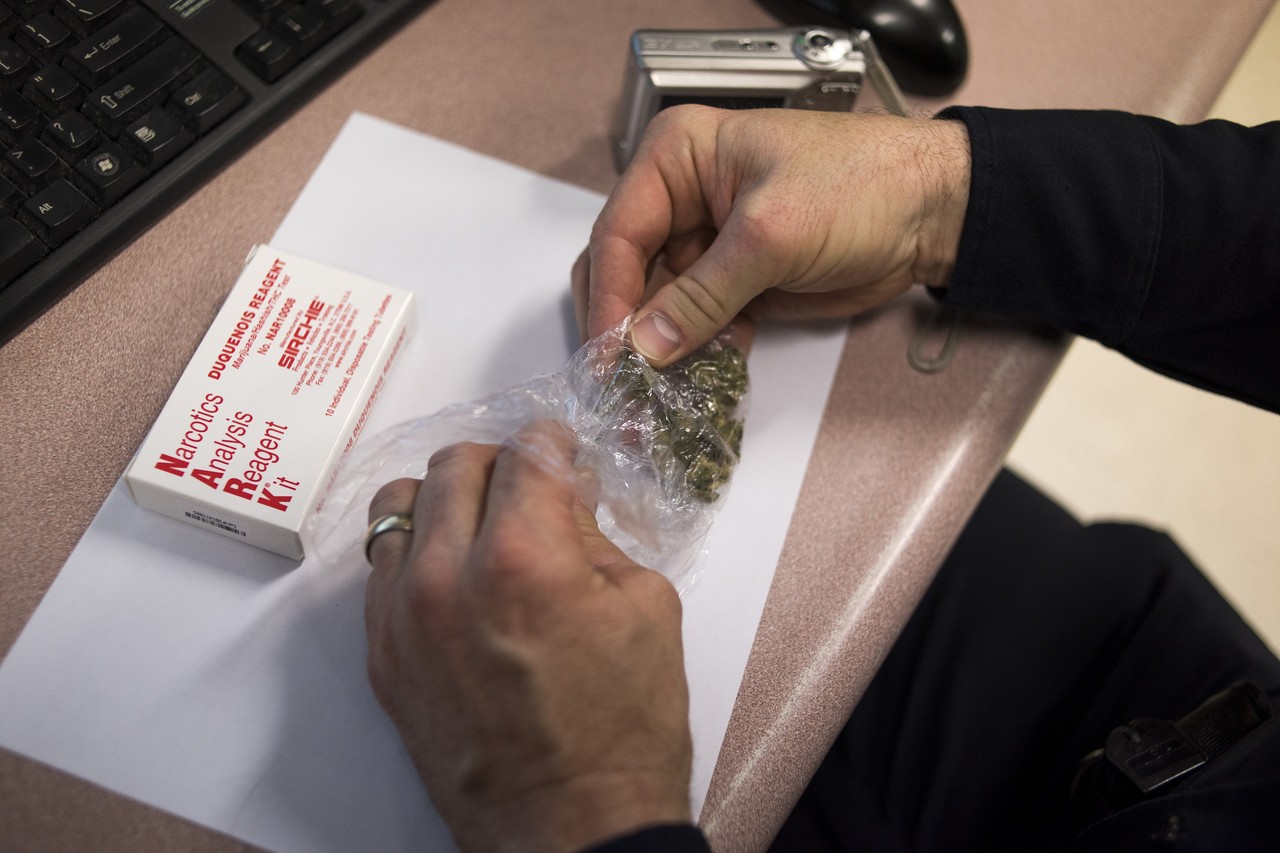

The opioid epidemic—and a lack of access to treatment—have compounded the damage. In Hardin County, prosecutor Brad Bailey said drug cases, which accounted for less than 20% of his criminal cases a decade ago, have surged to 80%.

The epidemic is spawning more thefts, including a rash of snatched air-conditioners sold for scrap metal, said Dennis Musser, police chief in Kenton. Linda Martell, a 69-year-old who moved to Kenton from outside Cleveland a decade ago to be near her daughter, was surprised a chain saw and heavy tools were stolen from her garage.

When she was a young adult, she recalled, “All the problems were in the big cities.”

Linda Martell, 69, walks home with her granddaughter, Charlie Martell, 6, on North Main Street in Kenton, Ohio. Photo: Ty Wright for The Wall Street Journal

In November’s presidential election, rural districts voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump, who pledged to revive forgotten towns by scaling back regulations, trade agreements and illegal immigration and encouraging manufacturing companies to hire more American workers. A promised $1 trillion infrastructure bill could give a boost to many rural communities.

Lawmakers from both parties concede they overlooked escalating small-town problems for years. “When you have a state like Florida, you campaign in the urban areas,” said former Florida Republican Sen. Mel Martinez. He recalls being surprised when he learned in the mid-2000s that rural areas, not cities, were the center of an emerging methamphetamine epidemic.

During the Bush administration, lawmakers were preoccupied with two wars, securing the homeland after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and rebuilding New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Barack Obama’s administration tried to lift rural areas by pushing expanded broadband access, but found that service providers were reluctant to enter sparsely populated towns, said former Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

Since the collapse of the housing market, real-estate appreciation in nonmetropolitan areas has lagged behind cities, eroding the primary source of wealth and savings for many families.

“We didn’t really have much of a transformation strategy for places where the world was changing,” Mr. Vilsack said.

Meanwhile, major cities once considered socioeconomic laggards have turned themselves around. In St. Louis, which has more than 30 nearby four-year schools, the percentage of residents with college degrees tripled between 1980 and 2015—creating a talent pool that has lured health care, finance and bioscience employers, officials say. Instead of people moving where the jobs are, “jobs follow people,” said Greg Laposa, a local chamber of commerce vice president.

In many cities, falling crime has attracted more middle- and upper-class families while an influx of millennials delaying marriage has helped keep divorce rates low.

Maria Nelson, a 45-year-old media company manager who came to Washington, D.C., to work after college, had always assumed she would someday move to the suburbs, where she had grown up. A generation of heavy federal spending helped make the nation’s capital one of the country’s highest-earning urban centers. Its median household income rose to $71,000 a year in 2015, a 51% increase since 1980, adjusted for inflation.

While Ms. Nelson was able to buy a brick row house in 2002, she said she worries about younger colleagues—let alone anyone moving in from a small town—who face soaring real-estate prices. “The whole area just seems to be out of range for most people now,” she said

In Kenton, Father Young said that despite their mounting troubles, he is optimistic about his parishioners. Some of them tell him they worry about what will happen when they die because they still provide for their adult children.

He likes to say there is always hope. “They can find a job,” he said. “Columbus is close enough.”