WSJ: American Farm Towns, With Changing Priorities, Reject Industrial Agriculture

Bill Skeet unloaded hay this month for his cattle in Tonganoxie, Kan., where a battle over a new Tyson Foods chicken-processing plant took place.

By Jacob Bunge | November 29, 2017

Meatpackers, including Tyson Foods and its chicken processing, struggle to win support for new plants

TONGANOXIE, Kan.—Rural Americans are turning their backs on the industry that made the U.S. the biggest meat-exporting country in the world.

Residents of Tonganoxie, a 5,300-person town in northeast Kansas, spent part of the fall hanging white-and-red placards that say “No Tyson in Tongie” on fenceposts and pickup trucks. Their efforts were part of a public push against Tyson Foods Inc., the largest U.S. meat processor by sales, which trumpeted in early September its plans to build a $320 million chicken-processing complex just south of town.

The investment, Tyson said, would bring 1,600 jobs to the area and deliver $150 million annually to the Kansas economy, in part because it would pay local farmers to raise chickens and buy locally grown grain to feed them. “Kansas will be an outstanding home for this Tyson complex,” said Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback, who joined Tyson staff and local elected officials in Tonganoxie when they unveiled the plan.

Many residents, including farmers, disagreed. Online, they raised alarms about groundwater pollution, infrastructure burdens and noxious smells. With a relatively strong economy, and job flexibility that comes from proximity to the Kansas City metropolitan area, many weren’t persuaded by the promised economic benefits. Critics railed at Tyson’s proposed plant on radio shows and in local newspapers, and crowded into city council and county board meetings by the hundreds.

The debate that split Tonganoxie is taking place across rural America, where communities from California to North Carolina have turned away meat plants. Even in farm country—Kansas is the top wheat-growing state and third in cattle production—fewer people these days are directly involved in the sector, which has been battered by the worst downturn since the 1980s.

Mr. Skeet put a ‘No Tyson in Tongie’ sticker on his truck. The plant’s impact on the 5,300-person town’s environment, roads and lifestyle would have been overwhelming, he said.

That means many residents are increasingly disconnected from businesses that drive the local economy, and meat-processing companies, which search for locations near grain fields, livestock and transportation, are finding it harder to build new plants.

Last year, some residents of Mason City, Iowa, successfully campaigned against a pork plant planned by Prestage Farms Inc. that the company said would have created about 920 jobs and slaughtered about 10,000 hogs daily. Some feared odors would foul the town’s “Music Man” square, named for hometown composer Meredith Willson’s Broadway hit. The company had promised a $240 million investment, and local officials had estimated a $750 million economic benefit.

Prestage is now building its plant 70 miles to the southwest, near the 3,400-person town of Eagle Grove, Iowa. Stan Watne, a county board supervisor who backed the plant there, said the decision was easy. “If we are going to save our schools, our way of life, we need people,” he said.

“Our current Eagle Grove site…is a better fit for our project,” said Jere Null, chief operating officer of Prestage Foods of Iowa. “[T]he economic activity occurring in the area is driving school expansions, residential expansion and supporting business expansion.”

Riceland Farms backed out of plans to build a beef-processing plant in Port Arthur, Texas, last year after residents of the 55,000-person town raised concerns about smells, the potential environmental burden and immigrant workers expected to staff the facility.

“We never had a thought that what we were doing was something that wouldn’t be accepted by the community,” said Nick Lampson, a spokesman for Riceland Farms, an investor-backed development group. “We thought we would be welcomed with open arms because of the number of jobs and the work we had done to create a clean, nonintrusive processing plant.”

Beef exports in the year to Sept. 30 have jumped 16% to $5.3 billion, according to the U.S. Meat Export Federation, fueled by growing demand in Asia. Pork and chicken exports are also up.

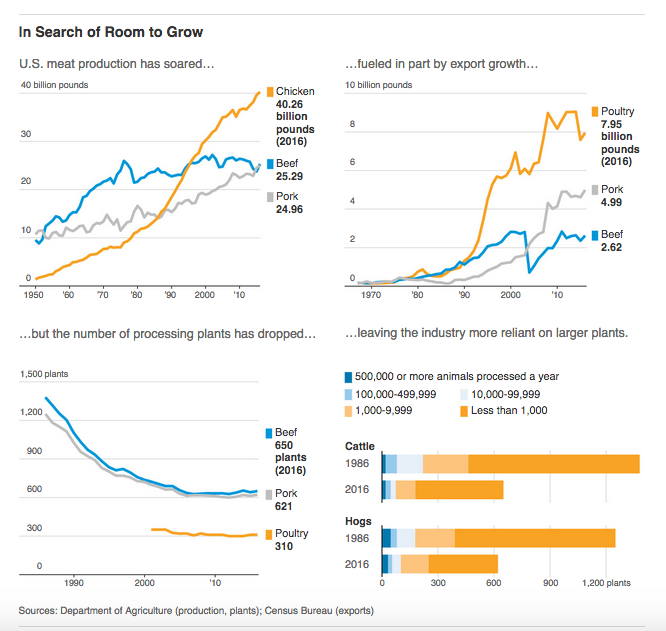

That’s one reason a larger numbers of animals are being processed at a smaller number of large-scale plants. In pork, 25 plants capable of slaughtering two million or more hogs annually now handle about 87% of all processing, with the largest 13 plants representing 60% of the total, according to the USDA. In 1986, the 19 largest plants handled about 50% of the pork industry’s processing.

The 19 largest beef plants process 70% of all cattle, and chicken plants have expanded capacity.

In Kansas, Tyson pitched chicken production as a way for farmers near Tonganoxie to pad their pocketbooks. Corn farmers’ average income is projected to be just two-thirds what it was in 2013, after a string of bumper harvests cut grain prices.

Many residents, including some farmers and ranchers, raised alarms about groundwater pollution, infrastructure burdens and noxious smells.

The chickens raised to supply Tyson’s proposed plant would consume about 12 million bushels of grain annually, farmers estimated, expanding the market for local crops.

Ken McCauley, who grows corn and soybeans on 4,500 acres about 60 miles north of Tonganoxie, figured the additional demand could mean an extra $18,750 to $37,500 in annual sales for his farm. He said the chance to also raise chickens for Tyson in the future could give his family more options to keep living off the land as farm costs rise.

“Everywhere in the country people tell you they want their food local,” Mr. McCauley said. “Then they turn around in the next breath and say ‘I don’t want that [plant] here.’ It really upsets me.”

About 10 miles north of Tonganoxie, Rodney Parsons grows corn and soybeans on about 1,000 acres, and raises cattle that are sold to nearby feedlots.

He conceded that meat plants need to be built, but Tyson’s proposed Tonganoxie complex—combined with the economic incentives the county had offered to attract the company—would have been “more of a burden to the local economy than an asset,” he said.

Standing near a pickup with a “No Tyson in Tongie” bumper sticker, Mr. Parsons said the trucks running in and out of the plant would require heavier road maintenance, and he suspected residents would wind up paying most of the difference. He was skeptical the plant’s presence would meaningfully boost grain prices for farmers, because meat companies like Tyson, based in Springdale, Ark., negotiate inexpensive grain supply deals with big commodity firms, he said.

Some residents said Tyson’s economic arguments held less power because Tonganoxie’s economy is solid. Average annual pay in Leavenworth County, where the town is located, is $43,797, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is well above Tyson’s average of $36,842 paid to its 5,700 Kansas employees, based on what the company said was a $210 million annual payroll for the state. The county’s unemployment rate in September was 3.7%, below both the state average and the national level.

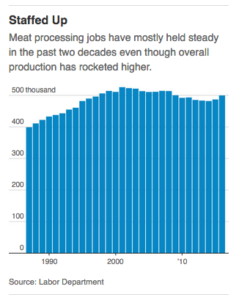

Agriculture is playing a smaller economic role as farms consolidate and technology reduces labor needs. In 2012, 444 U.S. counties depended on farming as a principal source of income and employment, down from 511 in 2001, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service.

The number of farms in Leavenworth County declined by 8.4% from 1982 to 2012, according to the USDA, and farmers harvested 18% fewer acres over that time. Three decades ago, the county ranked among Kansas’ top milk producers, but the number of dairy cows has dropped by more than 80% since then.

“Tonganoxie is a community that I would have defined as rural prior to this discussion” around Tyson’s proposed plant, said Jackie McClaskey, Kansas’ agriculture secretary. “Now I would say all of Leavenworth County is probably more suburban than I would’ve recognized.”

Some farmers said the modern meat industry looks nothing like the local or family-run operations they were familiar with growing up. Tyson’s proposed plant aimed to slaughter and process 1.25 million chickens a week.

“When we think about something of the magnitude of what Tyson wants to put in, that’s very scary,” said Angela Oelschlaeger, who raises beef cattle with her husband near Tonganoxie, where she said her family has been farming since 1890.

Ken McCauley, who grows corn and soybeans on 4,500 acres about 60 miles north of Tonganoxie, was in favor of the Tyson plant. He figured it would boost local grain prices and offer the option to raise chickens, benefiting farmers.

She said she read news articles about Tyson workers injured by anhydrous ammonia, a chemical used in meat plant refrigeration systems, including an incident in June at a Tyson facility in Hutchinson, Kan., about three hours away. Separately, in late September, Tyson pleaded guilty to violations of the Clean Water Act at a Missouri chicken facility.

“It’s always in the back of your mind, what can be in your water,” said Ms. Oelschlaeger, who said her family and cattle both rely on well water.

“Our operations are regulated by environmental laws and we’re committed to complying with them,” a Tyson spokesman said. “We’re also committed to continual improvement, which is why we employ environmental experts and also collaborate with third-party groups on ways we can do better.”

Outside groups such as Friends of the Kaw, a group from nearby Lawrence, Kan., that is focused on preserving the Kansas River, and Mercy for Animals, a national animal-rights group that campaigns against the meat industry, voiced support for the fight against Tyson. But both critics and supporters of the plant said the campaign against Tyson was driven by locals, who held meetings and rallied support on Facebook.

Tyson aimed to move fast in building the company’s first new plant in 20 years. Tom Hayes, Tyson’s chief executive, said on the company’s Aug. 7 earnings call that demand for chicken was “busting at the seams.” U.S. consumers this year are projected to consume a record 91.3 pounds of chicken each—the fifth consecutive year of growth—despite a rise in prices for some products.

To keep up, Tyson sometimes buys semiprocessed chicken from its competitors, which can cut into profits. In the quarter ended June 30, Tyson’s operating earnings from chicken fell by nearly 23%, despite sales climbing 4.6%. In response, Mr. Hayes announced on the earnings call that Tyson would speed its expansion in chicken processing.

Leavenworth County Commissioner Robert Holland supported the plant, which many of his constituents opposed. He said he found dead chickens hurled onto his lawn.

Kansas was already on Tyson’s map. State officials received a checklist of requirements to land the project: Access to a workforce of up to 1,600, proximity to major highways, a reliable water and power supply, and the ability to safely discharge wastewater. The focus turned to eastern Kansas near Interstate 70, and by late July Tyson was talking to Leavenworth County officials about Tonganoxie.

On Sept. 5, at a standing-room-only gathering at Tonganoxie’s Brunswick Ballroom, a historic reception hall downtown, Gov. Brownback and a host of state and Tyson officials said the company planned to buy 300 acres of land south of town and begin construction by mid-December.

Drew Overmiller, a Tonganoxie resident who campaigned against the plant, said in an interview that Tyson’s stated intent to break ground so quickly suggested to locals the complex was going to be built whether residents wanted it or not. That contributed to the backlash, he said.

Tabatha Regehr, a veterinarian, said she was in favor of Tyson’s plant, which could have supported a new library and a regional food bank. “People forget we need tax dollars, property tax, income tax, to make those things happen,” said Ms. Regehr, adding that the town’s stance toward agriculture has been skewed by transplants from nearby cities. “They’re living rural, but they’re not living an agriculture mind-set,” she said.

She said after she spoke up at a city council meeting, townspeople she knew called her “disgusting” and “disgraceful.” She said her address and other personal information were posted online by someone associated with an anti-Tyson group, prompting her to call the sheriff.

Leavenworth County Commissioner Robert Holland said he received so many angry letters that his mailbox wouldn’t shut. He said he found dead chickens hurled onto his lawn and had photos of mangled birds mailed to his home.

Two weeks after the plant was announced, county commissioners held a new vote on whether to revoke $500 million in incentives they had agreed to give Tyson and restart the evaluation process with public input.

Two weeks after the plant was announced, county commissioners held a new vote on whether to revoke $500 million in incentives they had agreed to give Tyson and restart the evaluation process with public input.

Only one commissioner voted to keep the incentives—Mr. Holland.

The decision doomed the plan for Tyson to build in Tonganoxie, and the company began looking elsewhere.

Earlier this month, in a conference call with reporters, Mr. Hayes, Tyson’s CEO, talked about why the plan failed. “We have not built a new plant since the 1990s, so one of the things we were really focused on…was how we were engaging the governor, the state ag officials,” he said. “And at the same time, I don’t know how in touch the officials were with the local sentiment in Tonganoxie and the surrounding areas.”

Last week, Tyson said it had found a community more receptive to a chicken plant—Humboldt, Tenn., a town of 8,500 about 85 miles northeast of Memphis. Tyson said the $300 million project, which received a tax abatement and has largely been approved by local officials, is expected to create 1,500 jobs and begin operations in late 2019.

Denton Parkins, a farmer who raises strawberries and pumpkins near Humboldt, said he anticipated some criticism from locals worried about odors and other aspects of Tyson’s plant. But he said that probably wouldn’t derail the plan. “Jobs are hard to come by,” he said. “Really, the county needs this.”

On Tuesday, Tyson said it remained interested in Kansas and would consider potential sites there in the future, although it said it had no specific timeline.