Washington Monthly: The Democrats Confront Monopoly

WASHINGTON, DC – JULY 21: Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) (L) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) talk during a news conference on the fifth anniversary of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the U.S. Capitol Visitors Center July 21, 2015 in Washington, DC. Senate Democrats praised the landmark legislation, including the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but said more work must be done to protect the financial security of all Americans. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Taking on corporate concentration has gone from a fringe idea to a key plank of the party’s strategy. Here’s how that happened—and why it matters.

On a Monday afternoon in late July, a group of leading Democratic members of Congress, including Chuck Schumer, Nancy Pelosi, and Elizabeth Warren, gathered in small-town Berryville, Virginia, to pitch the Democrats’ “Better Deal” economic agenda.

The party’s strategy for 2018 had been a topic of obsession since the day after the 2016 election. The Democrats were finally being forced to confront a fundamental weakness: the perception, as the comedian Lewis Black once put it, that while the Republicans are the party of bad ideas, the Democrats are the party of no ideas. Shortly after the election, Schumer had admitted on national television that one reason for Hillary Clinton’s loss had been the lack of a “strong, bold economic message.” In Berryville, he told the crowd, “Too many Americans don’t know what we stand for. Not after today.”

Sort of. The agenda’s tedious branding—the subtitle was “Better Jobs, Better Wages, Better Future”—drew mostly derision, not least for its resemblance to the Papa John’s motto: “Better Ingredients. Better Pizza.” A New Yorker humor piece listed “rejected slogans,” including “Not Perfect, But Also Not Trump.”

The problem went beyond the name. If the Better Deal was treated like an overstuffed grab bag of policies designed to placate the entire Democratic caucus, that’s because it was one. Much early coverage focused on a proposed tax credit for job training, the exact kind of centrist technocracy so many liberals were afraid of—“reminiscent of what Bill Clinton was selling in the 1990s,” as Michelle Cottle put it in the Atlantic.

The Democrats’ problem, then, isn’t that no one knows what they stand for on the economy. It’s that everyone knows what they stand for: higher taxes, more spending on social welfare, and a stream of opaque, nibble-around-the-edges government programs. Hillary Clinton may as well have said she had binders full of ideas.

Many commentators did, however, notice one element of the Better Deal that was quite new—and potentially transformative. If you got past the bland subheading “Lower the costs of living for families,” you would have found something very different from what anyone was selling in the 1990s: a section on “Cracking Down on Corporate Monopolies and the Abuse of Economic and Political Power.”

This anti-monopoly plank—which Schumer and Pelosi emphasized in op-eds in the New York Times and the Washington Post, respectively—reflected a growing awareness that the economy has become dangerously concentrated. In sector after sector, from retail to beer to eyeglasses, the market is controlled by a small handful of giant companies. And mounting evidence suggests that corporate consolidation is behind some of the economy’s deepest problems: income inequality, declining innovation, and the exodus of wealth and jobs from the heartland toward the coasts.

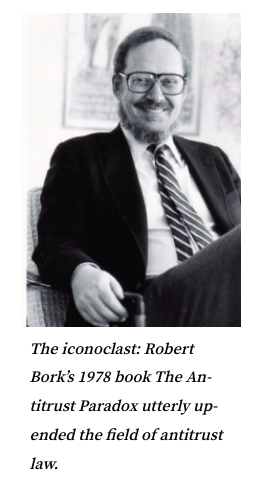

In 1978, Bork published The Antitrust Paradox, which utterly upended the field. The Court’s doctrine, Bork argued, was incoherent: it sought both to protect consumers from high prices and to protect small businesses from being squashed. Those goals were at odds with each other—paradoxical—because protecting small businesses from monopolies would allow them to charge higher prices.

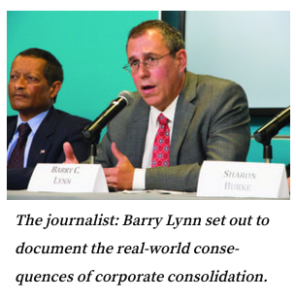

In 1978, Bork published The Antitrust Paradox, which utterly upended the field. The Court’s doctrine, Bork argued, was incoherent: it sought both to protect consumers from high prices and to protect small businesses from being squashed. Those goals were at odds with each other—paradoxical—because protecting small businesses from monopolies would allow them to charge higher prices. After the business magazine folded, in 2001, Lynn got a fellowship position at New America while he worked on a book about the frailty of the global supply chain, which came out in 2005. In his next book, Cornered, published in 2009, Lynn wrangled with the broader effects of a hyper-concentrated economy. That year, drained from writing two books back to back, he decided he needed a new strategy. Instead of spending years on another book, he would supervise a team of researchers. And instead of pumping out white papers like other think tanks, the team would produce original journalism.

After the business magazine folded, in 2001, Lynn got a fellowship position at New America while he worked on a book about the frailty of the global supply chain, which came out in 2005. In his next book, Cornered, published in 2009, Lynn wrangled with the broader effects of a hyper-concentrated economy. That year, drained from writing two books back to back, he decided he needed a new strategy. Instead of spending years on another book, he would supervise a team of researchers. And instead of pumping out white papers like other think tanks, the team would produce original journalism. “This is where the Barry Lynn stuff comes in,” Paul Krugman, the New York Times columnist and Nobel Prize–winning economist, told me. “Most people who do good economics do stuff partly based on statistics, on measurement, on data. But you always want a story that buys into lived experience. If you tell a story that fits the data but doesn’t sound at all like what you see in the world around you, then we’re very suspicious of that story.” The argument about consolidation both described the real world and fit the strange data economists had been observing. It had taken journalists, whose currency is reporting, not theory, to see it.

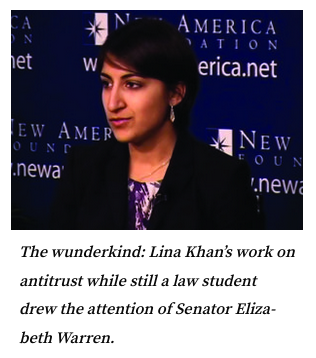

“This is where the Barry Lynn stuff comes in,” Paul Krugman, the New York Times columnist and Nobel Prize–winning economist, told me. “Most people who do good economics do stuff partly based on statistics, on measurement, on data. But you always want a story that buys into lived experience. If you tell a story that fits the data but doesn’t sound at all like what you see in the world around you, then we’re very suspicious of that story.” The argument about consolidation both described the real world and fit the strange data economists had been observing. It had taken journalists, whose currency is reporting, not theory, to see it. fBoy, was that good advice. Yale Law School, where students taking antitrust in room 120 can feel Robert Bork’s portrait smirking at the backs of their heads, is one of the most insidery institutions in America—a place where Harvard and Yale college grads outnumber those from all state schools combined, and where students begin gunning for Supreme Court clerkships before they get their first-year course schedule. Bill and Hillary Clinton met there. They had Bork as a professor.

fBoy, was that good advice. Yale Law School, where students taking antitrust in room 120 can feel Robert Bork’s portrait smirking at the backs of their heads, is one of the most insidery institutions in America—a place where Harvard and Yale college grads outnumber those from all state schools combined, and where students begin gunning for Supreme Court clerkships before they get their first-year course schedule. Bill and Hillary Clinton met there. They had Bork as a professor. “I’m not sure how much weight this set of issues can carry politically, but my hunch is, quite a bit,” he said. “It tells a story that both allows you to explain why things are going on but also has some hope of being susceptible to solutions.”

“I’m not sure how much weight this set of issues can carry politically, but my hunch is, quite a bit,” he said. “It tells a story that both allows you to explain why things are going on but also has some hope of being susceptible to solutions.” Schumer and his staff spoke with all forty-seven other Democratic senators, as well as leaders from the House, including Nancy Pelosi and the cochairs of the messaging committee. They also talked with people at the major liberal think tanks and survivors of the Clinton campaign, including Sullivan.

Schumer and his staff spoke with all forty-seven other Democratic senators, as well as leaders from the House, including Nancy Pelosi and the cochairs of the messaging committee. They also talked with people at the major liberal think tanks and survivors of the Clinton campaign, including Sullivan.