Vanity Fair: Inside Trump’s Cruel Campaign Against the U.S.D.A.’s Scientists

by Michael Lewis | November 2, 2017

The folks at the Department of Agriculture laid on a friendly welcome for the Trump transition team, but they soon discovered that most of his appointees were stunningly unqualified. With key U.S.D.A. programs—from food stamps to meat inspection, to grants and loans for rural development, to school lunches—under siege, the agency’s greatest problem is that even the people it helps most don’t know what it does.

Ali Zaidi was five years old when his parents moved him from Pakistan to the United States, in 1993. Later he’d marvel at American parents who agonized over the trauma that some trivial relocation—say, from Manhattan to Greenwich, Connecticut—might inflict upon their children. His parents might as well have put him in a rocket and shot him to the moon and no one made any fuss at all about it. His father wanted to study educational administration (“He loved the idea of helping to run the places people came to learn”), and the one place he knew someone willing to teach him worked at Edinboro University, in northwest Pennsylvania. And so the Zaidis left Karachi, a city of more than eight million Muslims, for a rural town of 7,000 Christians. “We went from solidly upper-middle-class to trying to reach into the middle class,” recalls Ali. The people in Edinboro didn’t have a lot of money, but Ali sensed that his family had less of it than most. “The other kids pay a dollar-fifty for school lunch and you pay 50 cents—you know something is going on, but you don’t really know what.” There was no particular reason he needed to figure out what was going on. But, in the most incredible way, he had.

Even as a kid he was interested in politics. That helped. He got that from his parents. “They spent a lot of time talking about society. Good and bad. Justice. About what we owe people,” said Ali. In rural Pennsylvania most people were Republicans. Ali became a Republican, too. “I believe in personal responsibility,” he said. “It’s exciting when people come together because of their faith to do something for their community. To care about something more than themselves.” In high school he volunteered for America’s Promise Alliance, Colin Powell’s foundation to help underprivileged children; he knocked on doors for the presidential campaign of George W. Bush. He ran track and excelled in the 400-meter dash. He was bright and ambitious and good at school. On a family trip to Boston he got his first, brief glimpse of Harvard and, without giving much thought to how he would pay for it, decided that was where he’d like to go to college. Faculty members at his high school thought Harvard was a bit of a stretch, and they encouraged him to apply to Penn State or the University of Pennsylvania, recalls Ali. He thought they were trying to lower his expectations. In the end he applied to Harvard, and only to Harvard, because, as he put it, “after you applied to one place, why would you waste money to apply to other places?”

Harvard admitted Ali to its class of 2008 and gave him financial aid. Around the same time, the C.E.O. of America’s Promise passed through rural Pennsylvania and asked to meet with volunteers. Ali went to the meeting, and one thing led to another: before he knew it Alma Powell, the group’s board chairman, asked him to join the America’s Promise board. At the time he thought this was preposterous. The America’s Promise board was filled with the biggest names in Republican politics and the C.E.O.’s of huge corporations. “I thought it was crazy,” recalls Ali. “They’d fly me to D.C. and put me up in a hotel.”

The Iraq War happened. Guantánamo Bay happened. Hostility toward his fellow Muslims found a greater welcome in his party than elsewhere. Yet Ali remained a Republican. Six or seven months after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast he traveled there, with America’s Promise, to help. In New Orleans he saw poverty he’d never imagined. “They had to rebuild these schools, and the kids were effusive,” he said. “The thing that got me was that they weren’t happy because they had just got their school back. They were effusive because suddenly they had a school that worked in the first place.” If you had asked Ali, before he went to New Orleans, what he thought of people who didn’t help themselves, he would have said, “My parents had to start all over again. What’s the big deal? Just suck it up.” The sight of little kids post-Katrina jolted him. “It kind of blew my mind: if you are in kindergarten you should at least get a fair shot. It was just eye-opening: to see how much your geography could determine the opportunities available to you.”

Now he sensed that poverty came in many flavors. He’d been lucky to have his particular parents and his particular community. He was reminded of the first time he’d run on a track with spikes. “You just fly on the track.” The poor kids he saw in New Orleans were trying to run the same race in life that he was. But he was wearing spikes and they weren’t. “There’s a real idealism that you have to indulge to think that people in New Orleans were now going to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. There were no bootstraps.”

He returned to college and rejoined the Harvard Republican Club. The surface of his life remained unchanged. But a new crackling sound in his head made the political program playing there more difficult to hear. One day he attended a debate between his two most famous professors: Michael Sandel, the philosopher, and Greg Mankiw, the economist who had served as chair of George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers. “Someone got up and asked, ‘If you are a storeowner after Katrina, should you hike up the price of flashlights?’ Greg Mankiw said yes, without hesitation.” Ali remembers thinking: Greg Mankiw is a good guy. But that answer is absolutely wrong. We don’t just have markets. We have values. “I started to think, Ah, man, I’m probably not a Republican.”

A year or so later he listened to a speech by the junior senator from Illinois, Barack Obama. One line from it stuck in Ali’s head: “Poverty is not a family value.” He worked as a field organizer in Obama’s campaign. “The biggest disappointment was that it was a little bit of a cliché: Harvard liberal,” said Ali. “Whereas my politics before were not a cliché.” Two years later he graduated from Harvard, and Obama was sworn in as president of the United States. Ali knew he had at least a shot at a very junior position in the new administration. “I had for whatever reason in my mind decided that I should go to the place where it wasn’t sexy but the sausage came together.” That place, he further decided, was the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. His first job in the new administration was to take the budget numbers produced by the senior people and turn them into a narrative: a document ordinary people could read.

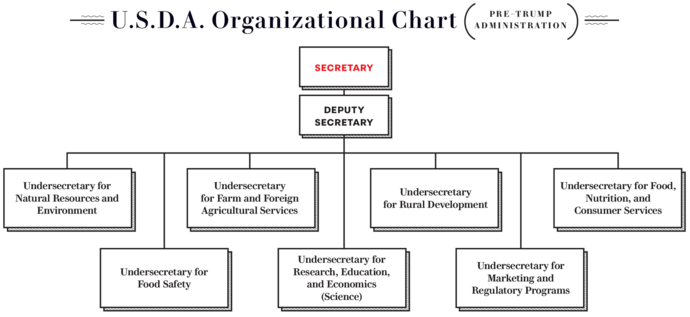

One day in his new job he was handed the budget for the Department of Agriculture. “I was like, Oh yeah, the U.S.D.A.—they give money to farmers to grow stuff.” For the first time he looked closely at what this arm of the United States government actually does. Its very name is seriously misleading—most of what it does has little to do with agriculture. It runs 193 million acres of national forest and grasslands, for instance. It is charged with inspecting almost all the animals people eat, including the nine billion birds a year. Buried inside it is a massive science program; a bank with $220 billion in assets; plus a large fleet of aircraft for firefighting. It monitors catfish farms. It maintains a shooting range inside its D.C. headquarters. It keeps an apiary on its roof, to study bee-colony collapse.

A small fraction of its massive annual budget ($164 billion in 2016) was actually spent on farmers, but it financed and managed all these programs in rural America—including the free school lunch for kids living near the poverty line. “I’m sitting there looking at this,” said Ali. “The U.S.D.A. had subsidized the apartment my family had lived in. The hospital we used. The fire department. The town’s water. The electricity. It had paid for the food I had eaten.”

To prepare for the transition after the 2016 election the U.S.D.A.’s staff had created elaborate briefings for the incoming Trump administration. Their written material alone came to 2,300 pages, in 13 volumes. A lot of people who work in the Department of Agriculture grew up on or around farms. They like to think of the Department of Agriculture as a nice, down-to-earth bureaucracy. They consider themselves more bipartisan, and less ideological, than people at the other federal agencies. “Our plan was to be as hospitable as possible,” said one of the transition planners. “We made sure the office space was gorgeous.”

To make the Trump people feel at home the U.S.D.A. people had set aside the nicest rooms on the top floor of the nicest building, with the nicest view of the National Mall. They had fished out of storage the most beautiful photographs from the U.S.D.A.’s impressive collection and hung them on the walls. They had brought in computers and office supplies, and organized a bunch of new workstations. When they heard that Joel Leftwich, the guy Trump wanted to lead his U.S.D.A. transition team, had been a lobbyist for PepsiCo, they brought in a mini-fridge stocked with Pepsis. That was just the way they were at the U.S.D.A. They didn’t think: How the fuck can people paid to push sugary drinks on American kids be let anywhere near the federal department with the most influence on what American kids eat? Instead they thought: I hear he’s a nice guy!

No one showed up that first day after the election, or the next. This was strange: the day after he was elected, Obama had sent his people into the U.S.D.A., as had Bush. At the end of the second day the folks at the Department of Agriculture called the White House to ask what was going on. “The White House said they’d be here Monday,” recalled one. On Monday morning they worked themselves up all over again into a welcoming spirit. Again, no one showed. Not that entire week. On November 22, Leftwich made a cameo appearance for about an hour. “We had thought, Rural America is who got Trump elected, so he’ll have to make us a priority,” said the transition planner, “but then nothing happened.” (The U.S.D.A. did not respond to questions from Vanity Fair.)

More than a month after the election, the Trump transition team finally appeared. But it wasn’t a team: it was just one guy, named Brian Klippenstein. He came from his job running an organization called Protect the Harvest. Protect the Harvest was founded by a Trump supporter, an Indiana oilman and rancher named Forrest Lucas. Its stated purpose was “to protect your right to hunt, fish, farm, eat meat, and own animals.” In practice it mainly demonized organizations, like the Humane Society, that sought to prevent people who owned animals from doing terrible things to them. They worried, apparently, that if people were forced to be kind to animals they might one day cease to eat them. “This is a weird group,” says Rachael Bale, who writes often about animal welfare for National Geographic.

One of the U.S.D.A.’s many duties was to police conflicts between people and animals. It brought legal action against people who abused animals, and so maybe it wasn’t the ideal place to insert a man who was preternaturally unconcerned with their welfare. The department maintained its composure—no nasty leaks to the press, no resignations in protest—even as Klippenstein focused, bizarrely, on a single issue. Not animal abuse but climate change. “He came in and wanted to know all about the office on climate change,” says a former U.S.D.A. employee. “That’s what he wanted to focus on. He wanted the names of the people doing the work.” The career staffer running the transition politely declined to give Klippenstein the names, but he said he bore no ill will toward him for asking. Klip—as he became known affectionately—had reassured everyone by saying, to anyone who would listen, that just as soon as this transition was over he was going straight back to his small livestock farm in Missouri. Bless his heart! Everything on the farm was still normal! (And just you never mind why Uncle Joe likes to be alone with his favorite sheep.)

It was obvious to everyone inside the U.S.D.A. that Klip was in an impossible position; no one person could get his mind around all the things the department did. Just a couple of weeks before the inauguration, Klip was joined by three other Trump people. The four-person team made a show of sitting down with some of the roughly 100,000-person U.S.D.A. staff to hear what they had to say. These briefings lived up to their name: the entire introduction to the U.S.D.A.’s vast scientific-research unit lasted an hour. “At most of the federal agencies, there were no real briefings,” says a former senior White House official who watched the process closely. “They were basically for show. The Trump transition sent in these teams in the end just to say they were doing it.”

The Department of Agriculture normally closes for business on Inauguration Day. It’s the only federal agency with an office building on the National Mall, which, once upon a time, had been the site of an experimental farm. The building is now used as a staging post during the inaugural by the National Guard and Secret Service. Just before the inauguration a Trump representative called the U.S.D.A. and said he wanted the building to remain open, as he was sending 30-something new people in. Why the sudden rush? Why force the government to turn on the lights and staff the cafeteria and go to the rest of the trouble to animate a federal building on a day no one was working? Even getting people into the building would be difficult, with snipers on the roof and the Metro station closed. A member of the Obama transition team wondered how the newcomers could have been vetted so quickly by the Office of Presidential Personnel. Nine months later, Politico published an eye-popping account about these new appointees. Its reporter Jenny Hopkinson obtained the curricula vitae of the new Trump people. Into U.S.D.A. jobs, some of which paid nearly $80,000 a year, the Trump team had inserted a long-haul truck driver, a clerk at AT&T, a gas-company meter reader, a country-club cabana attendant, a Republican National Committee intern, and the owner of a scented-candle company, with skills like “pleasant demeanor” listed on their résumés. “In many cases [the new appointees] demonstrated little to no experience with federal policy, let alone deep roots in agriculture,” wrote Hopkinson. “Some of those appointees appear to lack the credentials, such as a college degree, required to qualify for higher government salaries.”

What these people had in common, she pointed out, was loyalty to Donald Trump.