Two historians recount early-era beef industry

Two historians recount early-era beef industry

By Candace Krebs for Ag Journal

Posted Oct 9, 2019

As cattle producers wrestle with how the beef industry is structured and whether the entire beef chain adequately shares in the profits, two historians are promoting new books that trace how the post-Civil War era shaped the beef industry into what it is today.

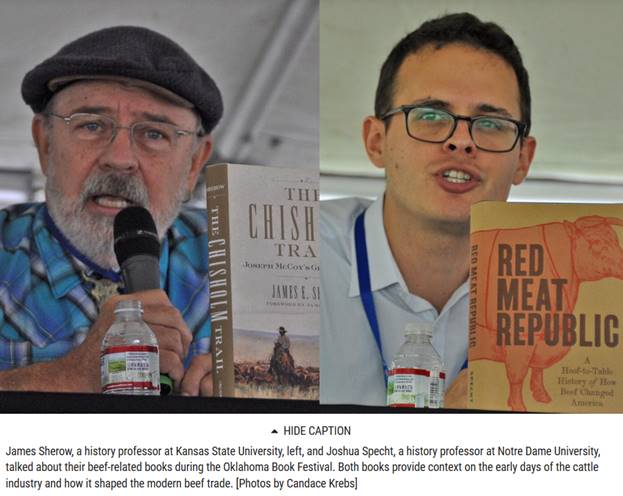

James Sherow, a history professor at Kansas State University, and Joshua Specht, a history professor at Notre Dame, appeared together on a panel during the Oklahoma Book Festival in late September.

Sherow, a fourth generation Kansan, described history as “social memory” that can shed light on the future by making sense of the past.

His latest book, The Chisholm Trail: Joseph McCoy’s Great Gamble, follows the life of one colorful cattle trader as he confronts the rapidly evolving factors that shaped the early frontier while aspiring to link southern cowboys with Midwestern cattle feeders and consumers on the increasingly populated East Coast.

As Sherow explains, bringing herds of straggly Longhorns up from South Texas by the thousands across what was then largely free grassland would play a key role in “democratizing beef.” While Longhorn beef was never served at the high-end dining establishments of the time, such as the Delmonico in New York City, it did make meat increasingly affordable for the masses.

From 1880 to 1900, urban residents swelled from 2.5 percent to 10 percent of the population, creating demand for a more centralized industry. Live cattle could be sold in New York for profits as high as $105 to $120 a head. But to get cattle in off the range to capture the potentially high margins, cattlemen had to contend with droughts, wildfires, blizzards, disease epidemics, Indian conflicts, market competition and unscrupulous dealers.

McCoy lost the shipping station he built at Abilene, Kan., after only a few years, as he battled setbacks that included a legal feud with the railroad over $5,000 in shipping commissions. But he was a natural promoter who went on to help establish other important cattle outlets at Wichita and at Denison, Texas, where one of the country’s earliest slaughter-and-shipping plants was located, and remained a believer in the cattle trails right up to the end.

At the first national convention of cattlemen, held in St. Louis in 1884, he succeeded at pushing through a resolution to create an industry-sanctioned south-to-north cattle route that would be fenced on both sides with bridge-like crossing structures at various points so domesticated herds could pass by without ever coming in contact with the tick-infested, disease-carrying Longhorns.

However, within months Kansas and Colorado both passed quarantines banning Texas cattle, which essentially put an end to the trail drives.

Ironically, although McCoy is widely credited with helping to create the cowboy myth, Sherow said the figure he truly revered was the land-owning stockman, who used his position to improve the local community and society as a whole.

Specht, of South Bend, Indiana, also follows the “democratization of beef” in his book, Red Meat Republic: A Hoof-to-Table History of How Beef Changed America.

He contends that no industry has done more to influence modern-day processing technology, business structure or government bureaucracies.

Many of the most controversial aspects of today’s industry — influence by outside investors, immigrant labor in packinghouses, a highly concentrated packing sector — emerged early in the 20th century and have changed little in the decades since, he asserts.

While the original big four Chicago packers centralized the processing sector in a way that benefited them financially, they could also successfully claim that they had “democratized” meat consumption, Specht points out.

The packers “did not want to deal directly with customers,” he writes. “That required knowledge of local markets and entailed a considerable mount of risk. Instead they hoped to replace the wholesalers.”

Once they controlled a city’s wholesale market, they became much more profitable and more powerful, he writes.

At the same time, Congress and the public were largely unsympathetic to the outcry from local butchers being put out of business. The butchers’ argument that lower cost meat from the packers was of substandard quality was widely considered elitist.

The centralized packing sector did encounter a more serious challenge when Teddy Roosevelt was elected president in 1904. Known as the “trust-busting” president, his personal emphasis on individualism and self-reliance made him suspicious of big business, Specht explains.

“Roosevelt railed against the trusts that dominated business in his day, and the Beef Trust became a natural target,” he writes. “The Chicago meatpackers had bankrupted thousands of local butchers scattered across the country. Moreover, they squeezed their profits from the same cattle ranchers Roosevelt admired.”

Roosevelt opposed unfettered commerce for the same reason he opposed socialism. He believed “unsupervised, unchecked monopolistic control in private hands” hindered individual initiative and the healthy development of personal responsibility.

At the same time, however, Roosevelt considered big corporations an inevitable outgrowth of industrialization, believing “the combination of capital in the effort to accomplish great things” had its place and should be “supervised and, within reasonable limits, controlled” rather than prohibited.

During the reform era, it was consumer concerns with food safety and affordable prices that ultimately won the day, resulting in the creation of bureaucracies like the Food and Drug Administration and the Federal Meat Inspection Service. Specht sees those developments as “the simultaneous embrace and regulation of big business” that somewhat counter-intuitively enshrined the heavily concentrated packing sector that still exists today.

“Big meatpacking was no longer questioned, it was regulated,” he writes.

The system prevailed in large part because consumers were thrilled with the growing availability of safe, affordable beef.

Specht recounts that in the early 1900s a pamphlet printed by Armour and Company proudly promoted the story of Billy the Bunco Steer, a prized animal that repeatedly led unsuspecting trainloads of cattle from the pens into the slaughterhouse.

“Back then the slaughterhouse and stockyards were a tourist attraction. That’s kind of changed now,” Specht said.

While both books end well before sophisticated meat alternatives begin to appear on the horizon, the authors were willing to weigh in on the subject.

“I don’t think beef is going anywhere,” Specht said. “But I do think this is starting a conversation about how we produce beef in this country that is going to lead to improvements.”

Sherow offered a similar response, acknowledging his own preference for grass-fed beef purchased directly from local farms.

“I think you’re going to see some changes in terms of how the industry is regulated and in feeding practices and the use of antibiotics,” he said. “All of these changes are coming, but at the same time I think beef will remain an important part of the American diet.”