The surprising truth about the ‘food movement’, By Tamar Haspel

The surprising truth about the ‘food movement’

By Tamar Haspel Columnist, Food January 26

Sales at farmers markets, the venues most closely associated with the food movement, peaked in 2007 and haven’t grown since. (Mark Moran/Associated Press)

Let me ask you a question: When it comes to our food supply, what do you care about?

Think about it for a second. Make a mental list.

Tamar Haspel writes Unearthed, a monthly commentary in pursuit of a more constructive conversation on divisive food-policy issues. She farms oysters on Cape Cod. View Archive

Now, let me ask you another question: Do you care about farmworker exposure to pesticides? I sure do, and I’m betting you do, too. But was it on your list? I’m betting it wasn’t.

And that difference, in a nutshell, is the source of a serious misconception about what we think of as “the food movement.” Ask people whether they care about a particular topic, and they’re likely to tell you — truthfully — that they do. But ask what people care about without prompting, and the fraction of people citing the issues that fall under food movement auspices – organics, local food, genetically modified organisms, farm subsidies, antibiotics, farmworker conditions, animal welfare — is actually quite small.

Take GMO labeling: Polls routinely show that, when you ask people whether they want GMOs labeled, upwards of 90 percent say yes. Overwhelming support for labeling GMOs! But if, instead, you ask consumers what they’d like to see identified on food labels that isn’t already there, a paltry 7 percent say “GMOs.” Almost no support for labeling GMOs!

[GMO

labeling: Is the fight worth it?]

That 7 percent study was done by William Hallman, professor and chairman of the Department of Human Ecology at Rutgers University, who points out that “most of the research that is out there that has tried to gauge how much people care about such things [has] asked people to react to lists of foods that are nasty or nice, and there are certainly social-desirability biases baked into the responses to such questions.”

The Rutgers study asked consumers about information on labels using both methods: first, “What would you like to see on labels?” and second, “Would you like to see X on labels?” The difference between the responses is huge, and it’s at the heart of why the food movement seems so much bigger than it actually is.

This grocery store in Boulder, Colo., touts the organic, GMO-free offerings at its soup bar. (Brennan Linsley/Associated Press)

When subjects were asked what they would like labels to identify, here were some of the results: 7 percent (the highest number) said GMOs, 6 percent said where the food was grown or produced; 2 percent said chemicals; 1 percent said pesticides. A survey by the International Food Information Council in 2014 asked a similar question; 4 percent of respondents cited biotechnology and 4 percent cited source or processing information. Those are very small numbers.

But when the Rutgers study asked the question the second way, 80 percent of respondents said it was somewhat, very or extremely important to them that GMO content be on the label. Pesticides? 83 percent.

The moral of this story is that it’s easy to make it look like people care a whole lot more than they do.

Where does that leave us? How many people really do care? Is there even such a thing as a food movement?

Asking what consumers would like to see labeled yields an incomplete measure, certainly. The public relations firm Ketchum, which works extensively with the food industry, has tried to pinpoint the kind of consumer we think of as part of the food movement: someone who regularly and publicly recommends or critiques foods or agricultural practices. The firm came up with a definition using those criteria and found that, in 2015, 14 percent of the population met them, up from 11 percent two years earlier.

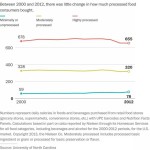

The Ketchum study indicates that food concerns among consumers are rising, something just about everyone I’ve spoken to believes to be true. But hard data on the foods that people actually buy indicate that old habits die hard.

Take organic foods. Sales growth has outpaced the rest of the market for many years, but organics still account for only 5 percent of the total market.

Local food sales make an even less compelling case. Sales at farmers markets, the venues most closely associated with the food movement, peaked in 2007 and haven’t grown since (although sale of local foods through restaurants and retail markets “appears to be increasing,” according to the Agriculture Department). The USDA estimates the total local-foods market to be about $6 billion, or about 1 percent of total food sales.

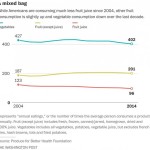

Meanwhile, our consumption of highly processed foods has held steady. But our fruit and vegetable consumption is a mixed bag. We’re buying more fresh and less canned, so the “fresh” message may be resonating. And we’re eating fruit 7 percent more often than we did a little over a decade ago (not counting fruit juice, which we drink considerably less of), but we’re eating vegetables 6 percent less often, which brings our total fruit and vegetable consumption down just a hair since 2004. Michael Pollan’s “eat food, not too much, mostly plants” is undoubtedly the best seven-word diet advice ever given, but it doesn’t appear to be catching on.

What explains the discrepancy between the common perception of a growing “food movement” and the disconcerting data on what people actually buy and eat? It could be the profound disconnect between the priorities of food movement leaders and those of food movement consumer participants.

A Washington Post op-ed by four of those leaders (including Pollan) summarized what we think of as “food movement” concerns: cutting pollution and greenhouse gases, improving conditions for farmworkers and livestock, and ensuring that Americans have access to safe, affordable, nutritious, “real” food.

[How

a national food policy could save millions of American lives]

For consumers, on the other hand, environmental, farmworker and animal welfare concerns take a back seat to their overwhelming first priority: their family’s health. Ketchum partner Linda Eatherton says the firm’s research indicates that “it all boils down to one thing. They care deeply about the health and safety of themselves and their family.” She notes that they also care about what’s going on in their communities and are beginning to register concerns about climate and environment, but, she says, “conversations about feeding the world fall very, very flat.”

Consumers’ fears for health don’t focus on declining vegetable consumption or the dietary dominance of highly processed foods. They are focused, instead, on a sense that they’ve been misled by the people and companies selling them food. “They feel all the information presented to them before was intended to hide important information,” says Eatherton.

Cereal maker Kellogg’s has announced it will remove all artificial colors and flavors from its products — which include Froot Loops, Corn Pops, Apple Jacks and Honey Smacks — by 2018. (Gene J. Puskar/Associated Press)

That may well explain why the increasing pressure consumers are exerting on food manufacturers hasn’t focused on, say, decreasing the fertilizer runoff that’s polluting our water but has, instead, driven moves such as Kellogg’s, last August, to remove all artificial colors and flavors from their products by 2018.

There’s not much evidence that switching from additives that are artificial to those that are natural will be a public health win, but “natural” — a word that the FDA hasn’t defined — seems to be what consumers are looking for. And natural sure sounds better than artificial. Even a hard-hearted empiricist like me, who has waded through the data and found very little support for the idea that natural is actually safer, can’t help but like the idea of “natural” food. We’re hard-wired to associate the word with purity, wholesomeness and, yes, safety.

[The

problem with processed foods isn’t what’s in them. It’s what isn’t.]

The strongest evidence of harm from artificial ingredients comes from research linking food dyes with behavioral problems in kids, and, even there, the evidence is mixed. Is it really in the public’s interest that parents feel better about Froot Loops? But Kellogg’s knows that the connection between what we eat and our health is tangible and accessible. The connection between what we eat and the Lake Erie algae bloom — fed by fertilizers, manure and sewage — that poisoned Toledo’s water supply feels distant and unreal.

The Campbell Soup Co. decided to cite any GMO ingredients on its packaging as a consumer right, though it said “the overwhelming weight of scientific evidence indicates that GMOs are safe.” (Gary Cameron/Reuters)

The bottom line is that consumers are pushing corporations to eliminate chemicals, preservatives and anything artificial — a deck-chair rearrangement exercise that probably won’t make our food more healthful but could both encourage consumption of the targeted processed foods (because they’re natural!) and, possibly, contribute to food waste (because preservatives do, indeed, preserve).

Meanwhile, absent pressure from consumers, progress on issues of planet, workers and livestock may be slow. Unilever, which has been out front on environmental health, has found that changing the way it sources ingredients to encourage responsible farming practices has been an uphill battle. Although there are some bright spots (cage-free eggs are increasingly popular, and many food-chain players are phasing out antibiotics in livestock), most corporate food-policy changes seem designed to appease consumers without making any real improvements.

Is there a food movement? Hallman at Rutgers says there is, but he says “it is much smaller than is assumed by many in government and the food industry,” and everything I’ve read and heard indicates that he’s right. The biggest problem, though, isn’t size but substance. As long as consumer concern about additives, chemicals and preservatives overshadows concern for the environment, workers and livestock, progress on those fronts may be stymied.

When eliminating preservatives from processed food we shouldn’t be eating anyway is what passes for progress, don’t look to consumer pressure for meaningful improvement. And that’s troubling, because, at the end of the day, we’ll get the food supply we demand.