The Press Democrat: Organic milk market sours for Sonoma County dairy farmers

by ROBERT DIGITALE | March 25, 2018

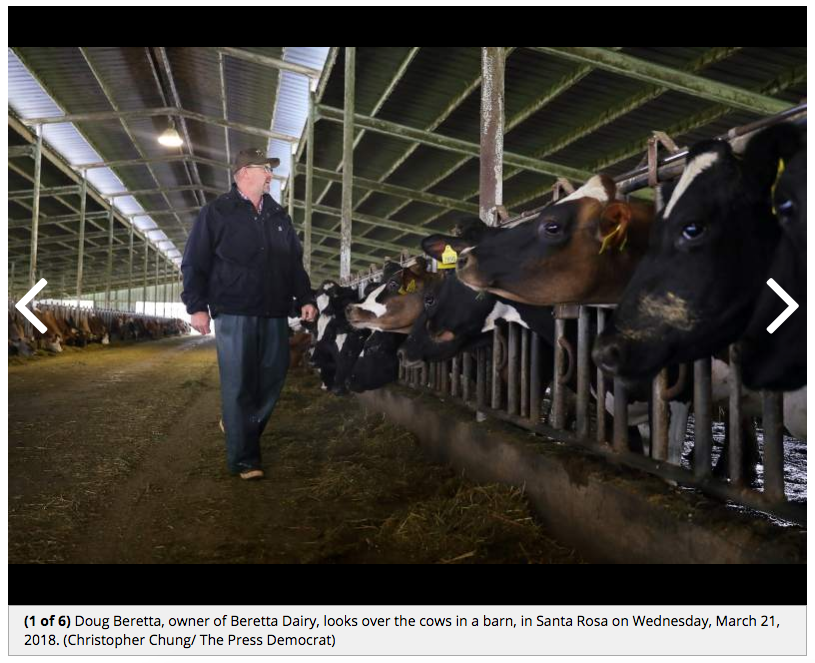

With gray skies drizzling upon him, Doug Beretta rode his all-terrain vehicle back to the milking barn after doctoring a downed cow.

The brown-faced Jersey had calved the day before and looked healthy that same night when Beretta checked on his animals. But the next morning the cow wouldn’t stand and showed signs of milk fever, a potentially fatal malady caused by low calcium levels in the blood. So Beretta, whose green overalls quickly became streaked with manure, slowly injected a solution of calcium and phosphorous into one of the cow’s veins. About an hour later the animal was back on its feet.

If only the third-generation farmer could find such effective medicine to turn around a struggling organic dairy industry.

Over the last 12 years, North Bay dairy farmers like Beretta have switched in droves from conventional milk production to certified organic operations. The conversions allowed them to earn a premium price for their milk and to gain more stability for their businesses as the market for conventional milk weakened.

But the U.S. today is awash in organic milk. Farmers have seen prices fall, and many worry whether their processors will keep taking their product.

“After Sept. 30, we have no idea if we will have a contract for our milk,” said Beretta, 54, who works the family’s Llano Road dairy west of Santa Rosa with his adult children.

11 solid years

Organic farming served the family well for 11 years, Beretta said. But since 2016 the farm’s income has fallen by a third, substantially reducing the margins between revenue and expenses.

The North Bay’s sweeping grasslands have been home to generations of dairy farmers. More than 150 years ago California’s first commercial dairy industry began in the headlands of Point Reyes.

For years milk was the region’s premier crop. Even today it ranks second after wine grapes, with dairy farmers in 2016 receiving $147 million for their milk in Sonoma County and $43 million in Marin County.

However, the North Bay has long been a more expensive place to farm than regions like the Central Valley. So for such crops as beef, eggs and milk, local farmers often look for niche markets that allow them to gain a higher price for their products and to avoid selling them as mere commodities. That has meant selling grass-fed beef, free range eggs and organic milk.

Two years ago 80 percent of the North Bay’s 90 dairies had been certified to sell organic milk. Beretta and others said today that figure is closer to 90 percent.

However, plenty of farmers around the U.S. also have gone organic in the last six years. The shift was prompted partly by tough times that conventional dairy farmers have experienced after the Great Recession.

In contrast, for most of that time organic farmers enjoyed profitable operations.

Many of the conventional farmers concluded “I’ve got to go organic or go out of business,” said UC dairy economist Leslie Butler.

Even as those new entrants came on the scene, many existing farmers reacted to rising prices by increasing the size of their organic herds. Butler and others said dairy farmers generally have the same game plan whether prices rise or fall. They milk more cows.

As a result, said Butler, “the market got flooded with organic milk.”

Income falling

Cuts in price and production quotas followed. In the last two years the income at many dairies has fallen by a third, said Richard Mathews, executive director of the Western Organic Dairy Producers Alliance.

“The farmers are really hurting,” he said.

Travis Forgues, vice president of farmer affairs for the Wisconsin-based Organic Valley cooperative and brand, said organic dairy prices can’t keep dropping and still provide a sustainable income for farmers. Nonetheless, the cooperative regularly hears from nonmembers in dire straits. Some tell of no longer having a place to sell their milk, not even for prices far below those paid on the organic market.

“They can’t even get on a conventional truck now,” Forgues said.

For the Beretta family, the oversupply comes at a time of change with their longtime organic dairy processor, Wallaby Yogurt of American Canyon.

Wallaby was sold two years ago for $125 million to Denver-based WhiteWave Foods. Then last year French dairy giant Danone completed an acquisition of WhiteWave for $12.5 billion.

Beretta, who began shipping to Wallaby when his farm switched to organic in 2007, recalled meetings at his kitchen table with the yogurt company’s owner. Now news about contracts and other matters comes from a Danone staff member based out of state.

Even as prices have dropped, the dairy faces other challenges. Among them, a recent California law requires state farmers by 2022 to start paying overtime when workers exceed 40 hours of work per week. And the city of Santa Rosa has told Beretta and other farmers along the Laguna de Santa Rosa that it wants them to start paying to receive treated wastewater, a product that for decades they’ve used for free to irrigate their pastures.

The family could build new milking facilities to reduce labor costs, as well as switch to automated systems that clean manure from barns. But such improvements require substantial investments and seem unlikely during a time of low milk prices and considerable uncertainty.

Nonetheless, Beretta, a county fair board director and a familiar face at the fair’s junior livestock auctions, said he expects to find a way to keep milking his 320 Holstein and Jersey cows.

Two adult children, daughter Jennifer and son Ryan, have joined him full time in the family business. His wife Sharon and a third daughter, Lisa, also help out with farm duties.

While he remains hopeful about staying in business, Beretta suggested the stability that organic production once provided seems to be slipping away.

“It’s not a niche market anymore,” he said.

A shared problem

That sense of change is shared by other farmers.

Sonoma dairy farmer Ray Mulas said organic farming for a time provided a better way to make a living “but then everyone got into it.”

Mulas, a third-generation farmer and fire chief for the Schell-Vista fire department, said his family milks about 800 cows, with roughly 600 of them at any one time certified for organic production. His brother, sister and he sell their milk to Petaluma-based Clover Sonoma, the Bay Area’s largest milk processor.

Longtime farmers all have gone through “a rough spell” or two, Mulas said. But if the outlook continues to darken, he suggested the family will carefully weigh whether it makes financial sense to keep farming.

“We’re not going to dig a hole,” Mulas said. “That much I know.”

Most expect the oversupply of organic milk to continue for at least the next year. Many predict that even when times get better, prices won’t be as lucrative as they once were.

“The margin to the farmers will never be like it was a few years ago,” said Marcus Benedetti, president and CEO of Clover Sonoma. A “massive number” of farms converted to organic production and brought “so much saturation” to the organic segment, he said.

Increased competition for conventional farmers also could continue to shake up the organic market.

“China is cranking up its own dairy industry,” said Butler, the UC dairy economist. India and South America also appear poised for expansion. Increases in the international milk supply likely will keep pressure on conventional U.S. dairy farmers and prompt more of them to consider switching to organic production.

In the grocery aisle, retail prices have started to soften, Benedetti said. But the declines lag the price drops for the farmers.

On Friday, a gallon of Clover organic whole milk cost $7.49 a gallon at Oliver’s Market on Stony Point Road in Santa Rosa. The price for a gallon of conventional Clover whole milk was $4.99.

The often double-digit growth of organic dairy products seems to have at least temporarily cooled. California organic milk sales increased 3.3 percent last year to 49 million gallons, according to the state Department of Food and Agriculture. Organic whole milk has shown steady growth for the last five years, but low-fat and non-fat categories declined in the same period.

Help from Clover

Clover plans to help its farmers weather this period of oversupply by paying an above-average price for organic milk, Benedetti said. The company currently is paying $30.40 per hundred pounds of milk, or a hundredweight, a standard dairy measure, compared to an average of $29.65 for six other local organic buyers, he said.

In contrast, California farmers this year on average are receiving less than $16 per hundredweight for conventional milk, according to Western United Dairymen, a Modesto-based dairy group. Part of that difference is the result of the greater costs associated with organic production, but the lower price also reflects the skimpier returns available in the conventional market.

Dairy processors generally expressed optimism that the local organic dairy farmers will survive the current downturn.

Before today’s consumers select a carton of organic milk, they want to know how the cow, the farmer and the land have been treated, said Benedetti. If processors take time to answer such questions about local farms, he said, “there will always be an organic dairy industry in Sonoma and Marin counties.”

The processors said the tough times have made clear the value of long-term relationships between farmers and milk buyers.

Forgues noted that Organic Valley was celebrating its 30th anniversary and has 2,000 farm families as members, with most of those in the dairy business. Nine members are North Bay dairy farmers. He said the cooperative doesn’t always pay the highest prices but seeks to offer stability for its members and works “to make sure the farmers are there today, tomorrow and in the future.”

Albert Straus, who in 1994 became the first certified organic dairy farmer west of the Mississippi and who went on to open the Petaluma-based Straus Family Creamery, said a risk today is that organic milk will become more of a commodity. He called it essential for processors and farmers to work together to create more stability regarding price and production levels.

He also said the two groups must keep educating consumers on the long-term benefits of organic production for the environment and for rural communities.

“I feel this is the way farming can be done and should be done,” Straus said.

Mathews of the Western Organic group said dairy farmers who sell to local processors like Straus and Clover likely have a good future. However, he expressed concern for those who have contracts with huge organic corporations.

“They’re going to have a tough time,” he said.

You can reach Staff Writer Robert Digitale at 707-521-5285 or robert.digitale@pressdemocrat.com.