The New Yorker: Exploitation and Abuse at the Chicken Plant

Case Farms built its business by recruiting immigrant workers from Guatemala, who endure conditions few Americans would put up with.

The law makes it hard to penalize employers, and easy for employers to retaliate against workers.Illustration by Cleon Peterson

A Guatemalan immigrant, Osiel was just weeks past his seventeenth birthday, too young by law to work in a factory. A year earlier, after gang members shot his mother and tried to kidnap his sisters, he left his home, in the mountainous village of Tectitán, and sought asylum in the United States. He got the job at Case Farms with a driver’s license that said his name was Francisco Sepulveda, age twenty-eight. The photograph on the I.D. was of his older brother, who looked nothing like him, but nobody asked any questions.

Osiel sanitized the liver-giblet chiller, a tublike contraption that cools chicken innards by cycling them through a near-freezing bath, then looked for a ladder, so that he could turn off the water valve above the machine. As usual, he said, there weren’t enough ladders to go around, so he did as a supervisor had shown him: he climbed up the machine, onto the edge of the tank, and reached for the valve. His foot slipped; the machine automatically kicked on. Its paddles grabbed his left leg, pulling and twisting until it snapped at the knee and rotating it a hundred and eighty degrees, so that his toes rested on his pelvis. The machine “literally ripped off his left leg,” medical reports said, leaving it hanging by a frayed ligament and a five-inch flap of skin. Osiel was rushed to Mercy Medical Center, where surgeons amputated his lower leg.

Back at the plant, Osiel’s supervisors hurriedly demanded workers’ identification papers. Technically, Osiel worked for Case Farms’ closely affiliated sanitation contractor, and suddenly the bosses seemed to care about immigration status. Within days, Osiel and several others—all underage and undocumented—were fired.

Though Case Farms isn’t a household name, you’ve probably eaten its chicken. Each year, it produces nearly a billion pounds for customers such as Kentucky Fried Chicken, Popeyes, and Taco Bell. Boar’s Head sells its chicken as deli meat in supermarkets. Since 2011, the U.S. government has purchased nearly seventeen million dollars’ worth of Case Farms chicken, mostly for the federal school-lunch program.

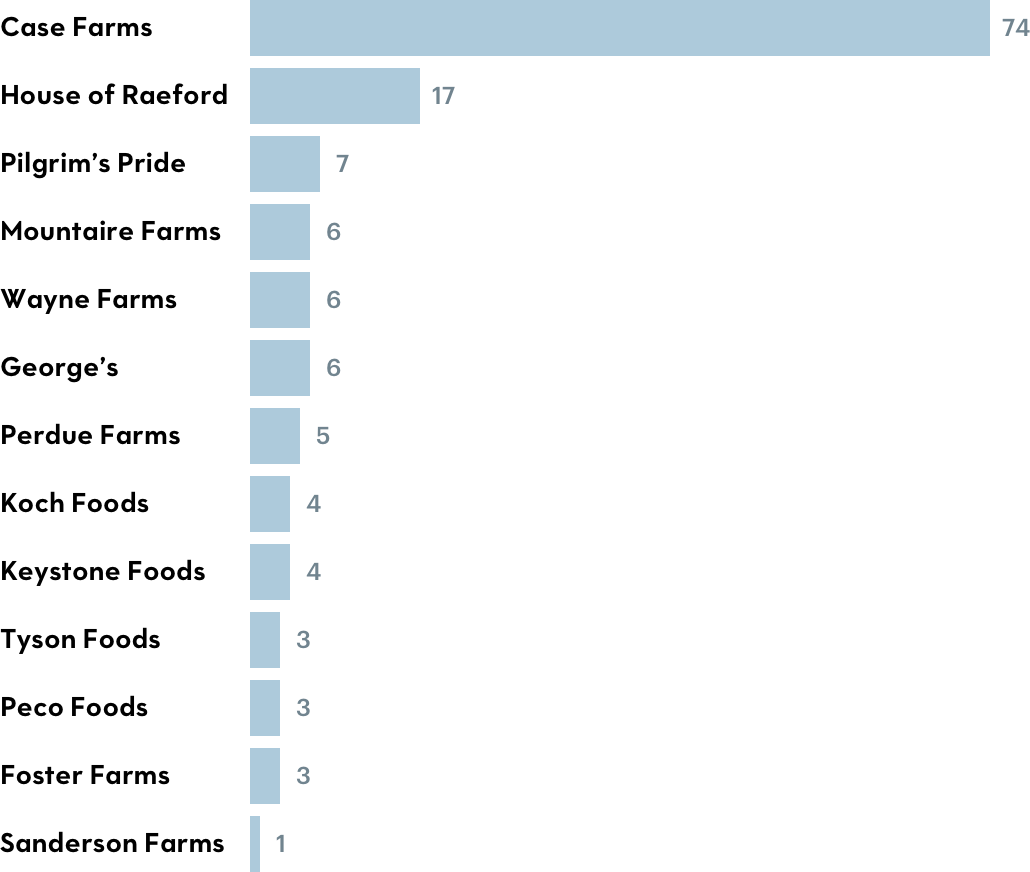

Case Farms plants are among the most dangerous workplaces in America. In 2015 alone, federal workplace-safety inspectors fined the company nearly two million dollars, and in the past seven years it has been cited for two hundred and forty violations. That’s more than any other company in the poultry industry except Tyson Foods, which has more than thirty times as many employees. David Michaels, the former head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), called Case Farms “an outrageously dangerous place to work.” Four years before Osiel lost his leg, Michaels’s inspectors had seen Case Farms employees standing on top of machines to sanitize them and warned the company that someone would get hurt. Just a week before Osiel’s accident, an inspector noted in a report that Case Farms had repeatedly taken advantage of loopholes in the law and given the agency false information. “The company has a twenty-five-year track record of failing to comply with federal workplace-safety standards,” Michaels said.

Case Farms has built its business by recruiting some of the world’s most vulnerable immigrants, who endure harsh and at times illegal conditions that few Americans would put up with. When these workers have fought for higher pay and better conditions, the company has used their immigration status to get rid of vocal workers, avoid paying for injuries, and quash dissent. Thirty years ago, Congress passed an immigration law mandating fines and even jail time for employers who hire unauthorized workers, but trivial penalties and weak enforcement have allowed employers to evade responsibility. Under President Obama, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agreed not to investigate workers during labor disputes. Advocates worry that President Trump, whose Administration has targeted unauthorized immigrants, will scrap those agreements, emboldening employers to simply call ICE anytime workers complain.

While the President stirs up fears about Latino immigrants and refugees, he ignores the role that companies, particularly in the poultry and meatpacking industry, have played in bringing those immigrants to the Midwest and the Southeast. The newcomers’ arrival in small, mostly white cities experiencing industrial decline in turn helped foment the economic and ethnic anxieties that brought Trump to office. Osiel ended up in Ohio by following a generation of indigenous Guatemalans, who have been the backbone of Case Farms’ workforce since 1989, when a manager drove a van down to the orange groves and tomato fields around Indiantown, Florida, and came back with the company’s first load of Mayan refugees.

Notes: Violation counts are current as of April, 2017. OSHA does not inspect every plant equally. The number of violations is influenced by the number of inspections, accidents, complaints, a plant’s previous record, and regional enforcement initiatives as well as over-all safety.

Sources: ProPublica analysis of Occupational Safety and Health Administration data. Employment numbers came from the most recent data available via Securities and Exchange Commission filings, company Web sites, and public statements.

Courtesy Lena Groeger / ProPublica

Just before the Presidential election in November, I toured Case Farms’ chicken plant in Canton with several managers. After putting on hairnets and butcher coats, we walked into a vast, refrigerated factory that is kept at forty-five degrees in order to prevent bacterial growth. The sound of machines drowned out everything except shouting. Thousands of raw chickens whizzed by on overhead shackles, slid into chutes, and were mechanically sawed into thighs and drumsticks. A bird, I learned, could go from clucking to nuggets in less than three hours, and be in your bucket or burrito by lunchtime the next day.

Poultry processing begins in the chicken houses of contracted farmers. At night, when the chickens are sleeping, crews of chicken catchers round them up, grabbing four in each hand and caging them as the birds peck and scratch and defecate. Workers told me that they are paid around $2.25 for every thousand chickens. Two crews of nine catchers can bring in about seventy-five thousand chickens a night.

At the plant, the birds are dumped into a chute that leads to the “live hang” area, a room bathed in black light, which keeps the birds calm. Every two seconds, employees grab a chicken and hang it upside down by its feet. “This piece here is called a breast rub,” Chester Hawk, the plant’s burly maintenance manager, told me, pointing to a plastic pad. “It’s rubbing their breast, and it’s giving them a calming sensation. You can see the bird coming toward the stunner. He’s very calm.” The birds are stunned by an electric pulse before entering the “kill room,” where a razor slits their throats as they pass. The room looks like the set of a horror movie: blood splatters everywhere and pools on the floor. One worker, known as the “backup killer,” stands in the middle, poking chickens with his knife and slicing their necks if they’re still alive.

The headless chickens are sent to the “defeathering room,” a sweltering space with a barnlike smell. Here the dead birds are scalded with hot water before mechanical fingers pluck their feathers. In 2014, an animal-welfare group said that Case Farms had the “worst chicken plants for animal cruelty” after it found that two of the company’s plants had more federal humane-handling violations than any other chicken plant in the country. Inspectors reported that dozens of birds were scalded alive or frozen to their cages.

Next, the chickens enter the “evisceration department,” where they begin to look less like animals and more like meat. One overhead line has nothing but chicken feet. The floors are slick with water and blood, and a fast-moving wastewater canal, which workers call “the river,” runs through the plant. Mechanical claws extract the birds’ insides, and a line of hooks carry away the “gut pack”—the livers, gizzards, and hearts, with the intestines dangling like limp spaghetti.

On the refrigerated side of the plant, there’s a long table called the “deboning line.” After being chilled, then sawed in half by a mechanical blade, the chickens, minus legs and thighs, end up here. At this point, the workers take over. Two workers grab the chickens and place them on steel cones, as if they were winter hats with earflaps. The chickens then move to stations where dozens of cutters, wearing aprons and hairnets and armed with knives, stand shoulder to shoulder, each performing a rapid series of cuts—slicing wings, removing breasts, and pulling out the pink meat for chicken tenders.

Case Farms managers said that the lines in Canton run about thirty-five birds a minute, but workers at other Case Farms plants told me that their lines run as fast as forty-five birds a minute. In 2015, meat, poultry, and fish cutters, repeating similar motions more than fifteen thousand times a day, experienced carpal-tunnel syndrome at nearly twenty times the rate of workers in other industries. The combination of speed, sharp blades, and close quarters is dangerous: since 2010, more than seven hundred and fifty processing workers have suffered amputations. Case Farms says it allows bathroom breaks at reasonable intervals, but workers in North Carolina told me that they must wait so long that some of them wear diapers. One woman told me that the company disciplined her for leaving the line to use the bathroom, even though she was seven months pregnant.

Case Farms was founded in 1986, when Tom Shelton, a longtime poultry executive, bought a family-owned operation called Case Egg & Poultry, whose plant was in Winesburg, Ohio. In the world of larger-than-life chicken tycoons, like Bo Pilgrim—who built a grandiose mansion in rural Texas nicknamed Cluckingham Palace—Shelton, with a neat mustache, a corporate hair style, and a mild manner, stood out. The son of a farmer, Shelton majored in poultry technology at North Carolina State, where he was the president of the poultry club and participated in national competitions in which teams of aspiring poultrymen graded chicken carcasses for quality and defects. Perdue Farms hired him right out of college, and he quickly rose through the ranks, attending Harvard Business School’s Advanced Management Program before becoming Perdue’s president, at the age of forty-three.

Case Farms was founded in 1986, when Tom Shelton, a longtime poultry executive, bought a family-owned operation called Case Egg & Poultry, whose plant was in Winesburg, Ohio. In the world of larger-than-life chicken tycoons, like Bo Pilgrim—who built a grandiose mansion in rural Texas nicknamed Cluckingham Palace—Shelton, with a neat mustache, a corporate hair style, and a mild manner, stood out. The son of a farmer, Shelton majored in poultry technology at North Carolina State, where he was the president of the poultry club and participated in national competitions in which teams of aspiring poultrymen graded chicken carcasses for quality and defects. Perdue Farms hired him right out of college, and he quickly rose through the ranks, attending Harvard Business School’s Advanced Management Program before becoming Perdue’s president, at the age of forty-three.

…to continue reading, click here.