The Garden City Telegram: ‘We’ve had this fear for years’: After Tyson fire, cattle producers look for options as prices tumble

By Sherman Smith | posted Aug 12, 2019

Cattle producers braced themselves Monday for tumbling market prices and ongoing uncertainty over the loss of meat processing operations at the Tyson plant in Holcomb.

Extensive damages from the Friday night fire closed the plant indefinitely, leaving cattle producers scrambling to look for alternatives.

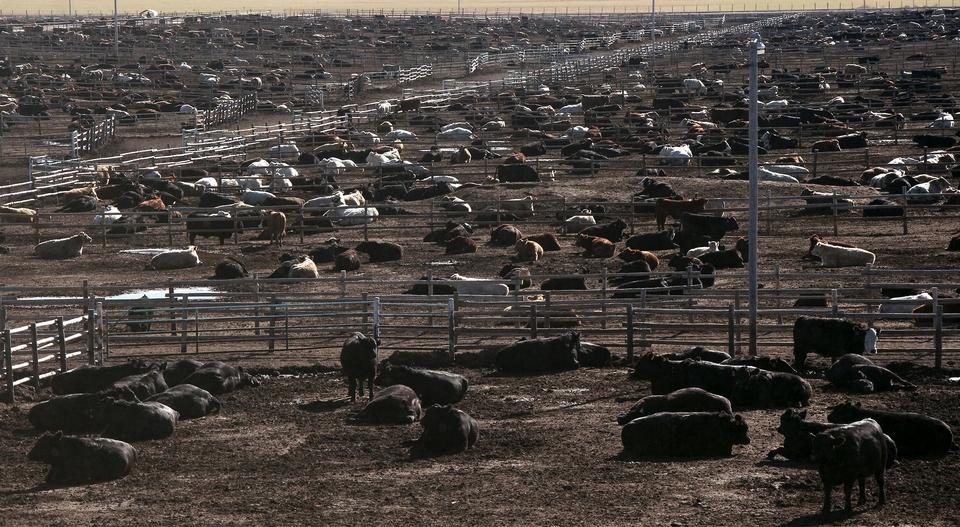

Industry insiders said the Holcomb plant was responsible for processing about 6,000 cattle per day, which accounts for about 6 percent of all the cattle processed in the United States.

Larry Jones, a Finney County commissioner and partner at J&O Cattle Co., watched the flames that wreaked havoc on the plant from his home a half-mile away.

“I knew Friday night, looking at the flames and everything, this is not good,” Jones said.

With a record number of cattle headed to market, Jones said, meat packing plants already were running at capacity.

“It’s always been a concern of everybody,” Jones said. “The packing capacity has not expanded with the cattle numbers. We’ve had this fear for years.”

In the first day of trading since the fire, cattle futures on Monday dropped $3 per hundred pounds, the maximum fluctuation allowed for a single day.

Based on typical market weights of 1,400 pounds per head, an extended drop in prices would mean a cattle producer with 1,000 cattle will lose $42,000 per day.

Anybody that had cattle that were not priced, that were waiting in the feedlot to be sold, their inventory already went down in value, so that kind of disruption has already occurred,” said Glynn Tonsor, an agricultural economics professor at Kansas State University.

Tonsor said it was difficult to assess the long-term impact without knowing how long the Holcomb plant will be down. The cattle that would have gone to the Holcomb plant will have to be re-routed, he said, and the associated costs will apply downward pressure on cattle prices.

“You’re talking more hours, more shifts, pushing those plants harder,” Tonsor said. “The cost to operate those other plants is going to go up because of labor and transportation.”

Tyson said it intends to rebuild, but the extent of damages and timeline for restoring operations is unclear.

“We’ll work to help our valued supplier partners find alternatives for their livestock during this ordeal,” said Worth Sparkman, a spokesman for Tyson.

Lee Reeve, owner of Reeve Cattle Co., which operates a feed yard in Garden City, said the nearest Tyson plants in Amarillo, Texas, and Lexington, Neb., are more than 200 miles away.

Cattle producers will find options, Reeve said, and prices eventually will reach parity. Still, he expects the loss of Tyson operations in Holcomb to “impact the whole industry.”

“It will adjust, but yeah, there’s a lot of anxiety,” Reeve said. “And it’s coming from a lot of different areas.”

Cattle producers already were dealing with uncertainty from trade relations and rising corn prices, Tonsor said. However, he also said the industry is large and diverse enough to withstand short-term diversity.

“We’ll survive,” Tonsor said, “but it’s going to require those adjustments, and there are economic consequences because of it. Some realism is important, but at the same time, it’s not the sky is falling permanently, either.”

Todd Domer, spokesman for the Kansas Livestock Association, said the organization has reached out to federal officials, including U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, and asked regulators to keep an eye out for irregularities in futures markets.

“I think the best news at this point that we’ve had is the Tyson officials, even though they said that plant is closed indefinitely, they have said that they plan to rebuild there in the same location,” Domer said.

Jones said he hopes Tyson can get the plant up and running within 30 days. If the plant is down for six months, Jones said, “we’ve got a problem.”