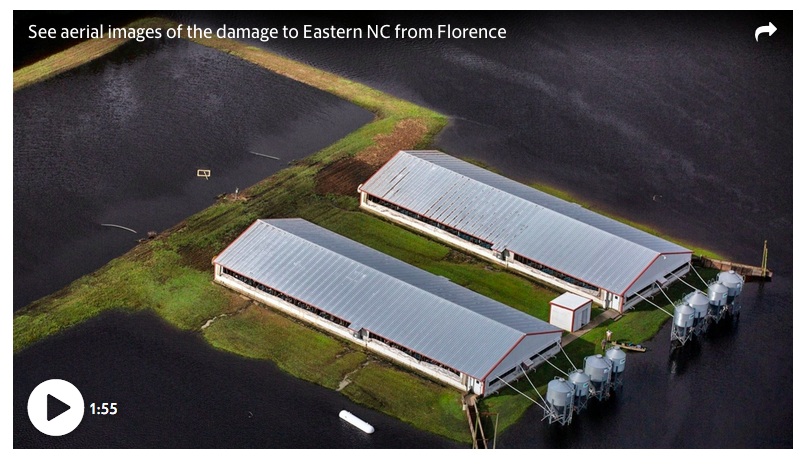

The Charlotte Observer: Florence kills 5,500 pigs and 3.4 million chickens. The numbers are expected to rise.

by John Murawski | September 18, 2018

The number of hogs and poultry killed in Hurricane Florence flooding is already double the casualties from Matthew in 2016, and the losses are expected to mount this week as new information comes in from farmers as they gain access to their properties.

Meanwhile, the number of hog waste lagoons in North Carolina that are damaged or overflowing continues to increase.

The N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services said Tuesday that so far 3.4 million chickens and turkeys have been killed by Florence, and 5,500 hogs have perished since the storm deluged the state. In preparation for the advancing storm, farmers were moving their swine to higher land, but the intensity of the flooding exceeded all expectations. The N.C. Pork Council said some of the hogs drowned in flood waters, and others were killed by wind damage to barns.

The agriculture agency provided no details as to which counties or farming operations suffered the losses. The only specifics have come from a note to investors issued by Sanderson Farms, saying that flooding claimed 1.7 million broiler chickens out of its 20 million in the state, ranging in age from 6 days to 62 days.

Sanderson Farms said that 60 broiler houses and four feeder houses were flooded. Farmers, who are contracted to Sanderson, could be out of power for as long as three weeks, and are running on emergency diesel fuel. Sanderson Farms noted that about 30 independent farms that supply its chickens are isolated by flood waters and unreachable at this time. Each of the farms houses about 211,000 chickens, totaling more than 6 million birds that can’t be reached with chicken feed.

Perdue Farms said it was largely spared by the storm.

“We experienced minimal impact on our live operations, with partial losses at two farms raising our chickens,” spokesman Joe Forsthoffer said by email. “Our feed mills are operating normally and we’re delivering feed to farms. We moved birds from low-lying farms in advance of the storm.”

During Matthew, which struck in October 2016, the poultry industry lost 1.8 million birds, while 2,800 hogs perished, according to the state Department of Agriculture. North Carolina farming operations total 819 million head of poultry and 9.3 million hogs.

The N.C. Department of Environmental Quality said Tuesday that four open air lagoons that store hog waste have structural damage, up from two known pits whose retaining walls were compromised as of Monday.

The environmental agency said 13 lagoons are overflowing from heavy rainfall and 55 are close to the brim and could overflow if water levels continue rising.

The agency has not inspected any of the 3,300 waste lagoons in North Carolina and is relying on self-reporting by farmers, said spokeswoman Megan Thorpe. Three regional agency offices are closed after Hurricane Florence and some state employees had to be evacuated due to rising water levels.

What’s more, it’s assumed that some farmers have not yet seen the state of their hog operations because they lack access to their properties.

The Pork Council, an industry advocacy organization, issued an advisory of its own saying that of the four that are compromised, only one lagoon is known to have breached. At that lagoon, on a small farm in Duplin County, the water flowed out through an opening in the wall, but the pit retained most of the fluids and solid waste material that sinks to the bottom of the lagoon, according to the Pork Council.

The organization said in a statement that damage to lagoons and spills appears to be limited.

“We do not believe, based on on-farm assessments to date and industry-wide surveying, that there are widespread impacts to the more than 2,100 farms with more than 3,300 anaerobic treatment lagoons in the state,” the council said.

Hog lagoons pose a potential environmental contamination risk because swine feces and urine contain bacteria and pathogens, including salmonella, E. coli and fecal coliform. Hog lagoons are the most common way farmers process pig waste, a treatment system in which microorganisms break down the waste matter into nutrients and byproducts that can be used as fertilizer.

North Carolina is one of the nation’s biggest livestock producers, ranking second in hog production; the state has more than 2,000 permitted swine farms and 9.3 million pigs.

H. Kim Lyerly, a Duke University professor of pathology and immunology, said that the contaminants from hog waste, mixed with other pollutants swept up by flood waters, can potentially expose vulnerable people to health problems.

“When you have a flood it’s a giant exposure of all the contents in the ground,” Lyerly said. “If you have a child or someone elderly or on a steroid inhaler or on chemotherapy, they may be more fragile.”

Lyerly is one of five Duke researchers who published a paper in the N.C. Medical Journal on Tuesday concluding that people who live near hog farm operations have higher rates of infant mortality, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia, and higher hospital admissions.

But John Classen, an N.C. State University professor of agricultural engineering, said the public health risk from hog lagoon spills may not be as great as the risk caused by the flooding of chemical industries and municipal waste water treatment plants. Classen said hog farmers draw down lagoon water levels during hurricane seasons, which allows the open pits to absorb heavy rains.

The water that overflows the rim of a lagoon is largely fresh water caused by rainfall, Classen said, and much of the bacteria is concentrated in the sludge that settles at the bottom as a byproduct of anaerobic digestion.

“The top is relatively dilute because of all the rainwater,” Classen said. “It’s not going to be as clean as rainwater, and I wouldn’t drink it.”

During major storms, uncovered lagoons can fill up with rain and overflow, or they can be flooded out by rising waters. The state has closed down 334 hog lagoons in flood plains since Hurricane Floyd in 1999, according to the N.C. Pork Council.

But spills continue to happen. After Hurricane Matthew in 2016, one hog waste lagoon failed, and 14 others were inundated, the council said. A May 2017 assessment of Matthew’s effects on the state’s water quality, conducted by the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, said that elevated levels of fecal coliform bacteria were found in waterways four months after the hurricane.

The report didn’t specify the source of the bacteria, but noted that such elevated levels are normal consequences of water runoff and flooding caused by hurricanes.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said Tuesday it is monitoring hog lagoons and coordinating with state regulators, as needed, to assess impacts to downstream drinking water.