Ten Questions with George Naylor, Board Member for the Non-GMO Project

Ten Questions with George Naylor, Board Member for the Non-GMO Project

Food Tank had the chance to speak with George Naylor, a Farmer and a Board Member for the Non-GMO Project, who will be speaking at this year’s Food Tank Summit in Washington, D.C.

Food Tank, in partnership with American University, is hosting the 2nd Annual Food Tank Summit in Washington, D.C. on April 20–21, 2016.

This two-day event will feature more than 75 different speakers from the food and agriculture field. Researchers, farmers, chefs, policymakers, government officials, and students will come together for panels on topics including food waste, urban agriculture, family farmers, farm workers, and more.

Food Tank recently had the opportunity to speak with George Naylor, a Farmer and a Board Member for the Non-GMO Project, who will be speaking at the summit.

Food Tank (FT): What inspired you to get involved in food and agriculture?

George Naylor (GN): I grew up on the Naylor Farm near Churdan, IA, which was bought by my grandparents in 1919 after farming several farms in Greene County since the 1890s. They were originally coal miners in England and then in Iowa. I still live in the beautiful house they built in 1919. My mom’s parents were farmers, too, in Boone and Webster counties, though they were always tenant farmers. Most of my aunts and uncles were farmers. We lived in small rural communities populated by many “characters,” but where we all respected and enjoyed our differences. My parents quit farming when I was in junior high and moved to Long Beach, California, so I experienced the contrast of life in the big city. As a farm kid, I saw my parents live up to the tradition of being jacks of all trades, which fit my inclination to be like the TV personality Mr. Wizard. Working outdoors in fresh air beat having my eyes water and lungs hurt from the smog in Long Beach. Luckily, my aunt Lil sent me a subscription to Rodale’s Organic Gardening and Farming Magazine, and the first Earth Day altered my consciousness in my last year at the University of California, Berkeley. A friend turned me on to the natural food movement that year, too, and I became a practitioner of Frances Moore Lappé’s book, Diet for a Small Planet. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until I actually came back to the farm and became active in various family farmer organizations that I realized how much farming is actually working against nature, and how the economic system forces farmers to be at odds with a healthy ecosystem or face extinction themselves.

Self-interest got me involved in these family farm organizations because the price of corn dropped 50 percent from the time I bought my farm machinery until my second harvest. This didn’t fit with what Earl Butz had told us—he said, “Plant fencerow-to-fencerow—the world needs your grain.” I learned that the political power of agribusiness had destroyed the parity farm programs of the New Deal, plunging farmers into constant crisis of the cost-price squeeze with a very few booms sprinkled in among many years of bust. This cheap grain policy forced farm consolidation and gave a comparative advantage to factory farm livestock production that externalized social and environmental costs. While New Deal farm programs supported family farms producing their own livestock feed with soil saving crop rotations and recycled nutrients, trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have globalized the cheap grain and an inhumane livestock model that pollutes our air and water like we are experiencing in Iowa and across the nation today.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity to fix the food system?

GN: The building of the more recent food movement has given me hope. So many everyday people, teachers, and students have read Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, in which I was featured as the Iowa corn and soybean farmer. People are really making efforts to eat healthily and find out how their food is produced. Unfortunately, the food movement hasn’t seemed to take to heart what I presented as a sound family farm and ecological farm policy. Food First has published a book, Food Movements Unite!, in which I spell out such a policy to get from our present destructive system that is out of control to a global democratic family farm system that values people and the planet. Globally, farmers and peasants embrace this democratic transformation with the concepts of food sovereignty and agroecology. The eternal optimist in me says someday there will be a food summit focused on this task.

FT: What innovations in agriculture and the food system are you most excited about?

GN: After 40 years of farming, I’m now transitioning half of my farm to organic and starting an organic cider apple orchard. It’s heartening to see the public demand healthier food produced with ecological methods. Now it’s time to “walk the walk,” and I’m impressed by how there’s much more research and farmer exchange on how to successfully make the transition. Groups like Practical Farmers of Iowa stand out in this regard.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero that inspired you?

GN: There have been many food heroes throughout history. Some of my most esteemed food heroes have been grassroots farm leaders going all the way back to the populist movement of the 1890s and the staunch defense of parity and peace by progressive Farmers Union leaders when they were under McCarthyist attacks during the Cold War. In my years of activism, I’ve witnessed energy developed at the grassroots by these leaders that has been astounding and awe inspiring. I’m sure they would ask, “Where was the food movement back in the day of American Agriculture Movement’s tractorcades, farm foreclosure protests of the 1980s, and demonstrations against factory farms invading family farm communities?” One leader who particularly inspired me was Nebraska farmer-activist Merle Hansen, who I talk about in my chapter in Food Movements Unite! Willie Nelson and Neil Young with their Farm Aid concerts and fundraising to help support grassroots groups need special recognition. Of course, I also admire brave journalists like Michael Pollan and authors and rabble-rousers like Jim Hightower (former Ag Commissioner of Texas).

FT: What drives you every day to fight for the bettering of our food system?

GN: The beautiful planet and all its diverse inhabitants including plants, animals, and human beings—an inheritance of billions of years of evolution—is what drives me for a democratic system that values them more than the right to turn Mother Nature into giant fortunes. (I was reminded this spring by the many colorful disease-resistant offerings in garden seed catalogs that have taken the Safe Seed Pledge—non-GMO.) My home state of Iowa has the most human-altered landscape of any state in the Union, and yet I’m not sure many Iowans, let alone my fellow United States citizens, recognize the destruction that has happened and is happening to their natural inheritance. Just as with mountaintop removal for energy in Appalachia, farming in Iowa is doing the same thing, but we didn’t start out with mountains. Compromising our natural genetic inheritance by altering the basic building blocks of life through chemical companies’ genetic engineering has to be the most disturbing current phenomenon. This is intended to expand the monocropping of commodity crops, which can only be more devastating to what we leave our descendants. These concerns drive me to be on the boards of the Center for Food Safety and the Non-GMO Project, and to be active in the grassroots organizing group, Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement.

FT: What’s the biggest problem within the food system our parents and grandparents didn’t have to deal with?

GN: My parents and grandparents lived through the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Those disasters were emblematic of the political, economic, and environmental challenges that farmers faced through the centuries from the basic economic and political assumptions of “market forces,” and, as Wendell Berry and many other analysts have pointed out, the demands of the cities versus the needs of rural economies. The Great Depression for farmers actually started at the close of World War I with a collapse of farm prices. They were proud to be raising food for the nation, but it wasn’t until Roosevelt’s New Deal with the agricultural leadership of Henry A. Wallace that policy dealt with the overproduction of farm commodities and the plague of “surplus labor.” The better aspects of Wallace’s farm policy that included minimum prices, conservation, supply management, and reserves of storable commodities (Ever-Normal Granary) meant that rural economies were stabilized, farmers would not be forced to push the limits of their land to mistakenly try to expand production to increase income, and food shortages weren’t necessary to raise farm income.

Today, the major problem facing everybody who eats or produces food is that the lessons of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, along with the New Deal policies to deal with the inherently destructive nature of agricultural markets, has been forgotten and, even worse, demonized by people in power.

The food movement often repeats the canard that farmers produce corn and soybeans because these crops are subsidized, as if the subsidy system was designed to benefit farmers. Let me make this clear: farmers produce “storable commodities” because they are not perishable and can be turned into cash like crude oil or iron ore—commodities demanded by our industrial economic system. The subsidy system only keeps commodity prices low without jeopardizing the solvency of the system that produces them.

FT: What’s the first, most pressing issue you’d like to see solved within the food system?

GN: Other than dealing with the basic economic reforms mentioned above, the threat of genetic modification of crops threatens the integrity of a functioning ecosystem and must be stopped. These crops were released on the market without compelling reasons, but solely for the benefit of the chemical companies and the cheap food, profit-driven industrial processing, and marketing corporations. Herbicide-resistant crops like Monsanto’s Roundup Ready crops allow industrial monocropping horizon-to-horizon on virgin land on any continent of the world. Besides, these crops are mostly feed grains and oil seeds like corn and soybeans that fuel global livestock production in factory farms along with biofuel refineries. Contrary to the claims of the World Food Prize, which we protest annually in Iowa, these crops are not intended to “feed the world,” but to create resource-intensive meat, milk, and eggs (and biofuels) for the wealthier classes of people in every nation—and to increase corporate profits.

FT: What is one small change every person can make in their daily lives to make a big difference?

GN: Eat right, speak politically correctly about our fellow citizens and the planet, and remind everybody that our political and economic system is not democratic but is being run for the benefit of billionaires. We need to explain to our fellow citizens that we are recruited to support our own demise by accepting the idea that cheap food and energy are good things that can be supplied by whatever technology multinational corporations can produce and use with only the real intention of increasing their bottom lines.

FT: What’s one issue within the food system you’d like to see completely solved for the next generation?

GN: The biggest obstacle to reform is the notion that entrepreneurship and “market forces” can solely solve our problems. We see daily where pioneering organic companies sell out to giant corporations and the organic standards are under threat from organic marketers. More and more, organic food is sourced overseas where land, labor, and lax certification can be exploited—out of sight, out of mind. In agriculture, or any natural resource sector, market forces dictate the drive for cheaper raw materials and labor. If federal or international policy ignores or, worse, fosters this paradigm, we will be stuck with a degraded planet, unhealthy food, and an impoverished citizenry. Are we supposed to ignore the original feature of the organic ideal: that organic would foster small, sustainable local farms?

FT: What agricultural issue would you like for the next president of the United States to immediately address?

GN: I believe that it is a mistake to look at agriculture or food policy in isolation from our general crisis of democracy. Therefore, it will be even less fruitful to look at “issues” within our food and agriculture system. We (and the planet) are in this together.

To find out more about the event, see the full list of speakers, and purchase tickets, please click HERE. Interested participants who cannot join can also sign up for the livestream HERE.

To join us at Food Tank’s São Paulo, Brazil Summit in September 2016, please click HERE. To join us at Food Tank’s Sacramento, CA Summit on September 22–23, 2016, please click HERE. To join us at Food Tank’s Chicago, IL Summit on November 16–17, 2016, please click HERE.

Want to become a sponsor of the Food Tank Summit? Please click HERE.

Want to suggest a speaker for one of the Summits? Please click HERE.

Want to watch videos from last year’s Food Tank Summit? Please click HERE.

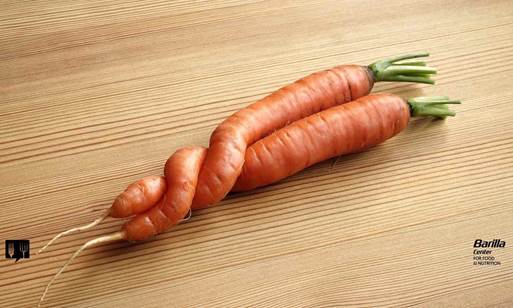

Sponsors for this year’s Food Tank Summit in Washington, D.C. include: Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition, Chaia DC, Chipotle, Clif Bar, D.C. Government, Driscoll’s, Edible DC, Elevation Burger, Fair Trade USA, Food and Environment Reporting Network, Global Environmental Politics Program of the School of International Service, Greener Media, Inter Press Service, Leafware, Niman Ranch, Organic Valley, Panera Bread, and VegFund.

Join the discussion using #FoodTank across Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter!

by Lani Furbank

Lani Furbank is a writer and photographer based in the DC metro area, where she covers the intersection of food, farming, and the environment for local and national publications. She studied broadcast journalism and environmental studies at James Madison University, and is passionate about supporting small-scale farms through mindful food choices and increasing access to nutritious food for communities around the world. Find her on social media: @lanifurbank