Shorthand: Cargill: The Worst Company In the World

Foreword: Congressman Henry A. Waxman

Cargill is the United States’ largest privately held company, bigger even than the notorious Koch Industries. Its footprint extends around the world. But The Worst Company in the World? We recognize this is an audacious claim. There are, alas, many companies that could vie for this dubious honor. But this report provides extensive and compelling evidence to back it up.

The people who have been sickened or died from eating contaminated Cargill meat, the child laborers who grow the cocoa Cargill sells for the world’s chocolate, the Midwesterners who drink water polluted by Cargill, the Indigenous People displaced by vast deforestation to make way for Cargill’s animal feed, and the ordinary consumers who’ve paid more to put food on the dinner table because of Cargill’s financial malfeasance — all have felt the impact of this agribusiness giant. Their lives are worse for having come into contact with Cargill.

In my 40-year long career in Congress, I took on a range of companies that engaged in abusive practices. I have seen firsthand the harmful impact of businesses that do not bring their ethics with them to work. But Cargill stands out.

In contrast to the oil and tobacco industries, for instance, the bad practices documented here are not inherent to the products Cargill sells, and are, in fact, entirely avoidable. For example, perhaps Cargill’s largest negative impact on the natural world is its role in driving the destruction of the world’s last remaining intact forests and prairies. There are more than one billion acres of previously degraded land where crops can be grown without further imperiling native ecosystems, at no additional cost. Similarly, other companies grow animal feed at large scale without the same levels of water or climate pollution.

From palm oil in Southeast Asia to agriculture here in the United States, Cargill has sat out industry efforts to improve. To address these gaps, over the last five years, the Mighty Earth team has engaged in extensive, high-level discussions with Cargill. Our team praised the company in 2014 when CEO David MacLennan committed to end deforestation throughout the company by 2020, and later when it committed to stop sourcing cocoa from inside national parks.

In January, we shared a draft of this report with Cargill. Days before its scheduled release, Mr. MacLennan called us to request a few weeks to consider our findings and, more importantly, our recommendations for change. We agreed to give Cargill the chance. Two weeks later, he committed that Cargill would adopt policies to prevent the destruction of native habitat, and that he would personally lobby other CEOs in the industry to do the same.

Unfortunately, these last months have only confirmed the company’s inability to respond effectively, and Mr. MacLennan’s inability to deliver real change.

Within days of his commitment, Mr. MacLennan’s second-in-command publicly questioned the value of strict policies to protect native habitat. It took Cargill months to hold meaningful discussions with other companies that had already adopted strong sustainability policies, or to address relatively simple issues in their palm oil supply chain that other companies had dealt with long ago. Meanwhile, we kept receiving data, outlined in this report, of Cargill’s serious ongoing problems with deforestation and child labor.

Despite the challenges, we held off on the campaign for five months in hopes that discussions would give Cargill a chance to change. Unfortunately, David MacLennan’s commitments didn’t seem to translate into meaningful action by others in the company. We were particularly disappointed when Cargill released a “Soy Action Plan” that permits suppliers to continue deforestation, and more recently when it issued a letter to its suppliers opposing the spread of forest conservation policies to the Brazilian Cerrado. These actions were a direct refutation of Mr. MacLennan’s commitments. We’ve successfully worked to improve the environmental and human rights practices of dozens of companies, but have never encountered a company that has such difficulty translating high-level commitments into action.

While Mr. MacLennan seems to want to do the right thing, he appears unable to decide between those who believe Cargill can do better and those who want to keep the bulldozers running. Unfortunately, because the status quo is deforestation, child labor, and pollution, Cargill’s dithering results in a continuing environmental and human rights disaster. And because Cargill’s reach is so broad, they drag other companies into aiding and abetting their environmental destruction and human rights abuses too.

Supermarket giant Ahold Delhaize (owner of Giant, Stop & Shop, Hannaford, Food Lion, and other brands) may say it wants to provide responsible meat, but it cannot do so as long as it is in a joint venture with Cargill to supply their store branded meats. The “Science Based Climate Target” trumpeted by McDonald’s lacks meaning as long as Cargill, the manufacturer of their Chicken Nuggets and Big Macs, drives climate pollution on a massive scale.

These companies — and more than a hundred others — have repeatedly called on Cargill to change. But Cargill has just as repeatedly defied these calls. If these businesses want to fulfill their environmental and human rights policies, they must go beyond polite encouragement to shifting their purchases to more responsible companies.

Only by holding Cargill and its customers publicly accountable can we force them to change. Concerted action by citizens and consumer companies has driven enormous progress in many parts of the food and agriculture industry. Now it is time for the company that purports to be a leader in that industry to finally act like it.

Henry Waxman

Former Member of Congress; Chairman, Mighty Earth

The worst company in the world. We recognize that this is an audacious claim. But when it comes to addressing the most important problems facing our world, including the destruction of the natural environment, the pollution of our air and water, the warming of the globe, the displacement of Indigenous peoples, child labor, and global poverty, Cargill is not only consistently in last place, but is driving these problems at a scale that dwarfs their closest competitors.

That Cargill would make a grand commitment and then ignore it shouldn’t be a big surprise.

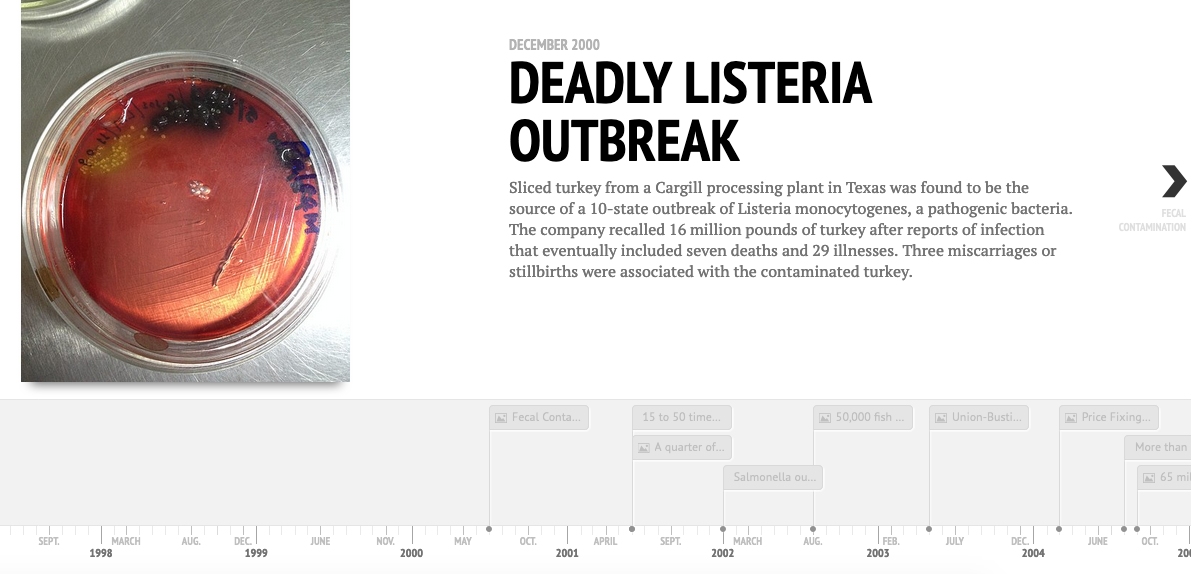

From having their membership in the Chicago Board of Trade suspended shortly after incorporating for trying to corner the market on corn and artificially drive up its price, to being responsible for the distribution of more than 150,000 pounds of contaminated beef to supermarkets just last year — Cargill has a long and sordid history of duplicity, deception and destruction. Just the past two decades provide dozens of examples.

See PDF here.

A Timeline of Cargill’s Impact:

Use the left and right arrows to explore two decades of Cargill’s destructive past. See citations here.

A Pattern of Deception and Destruction

Today, one privately-held company just may have more power to single-handedly destroy or protect the world’s climate, water, food security, public health, and human rights than any single company in history. And it’s not an oil company or a coal company, or any of the usual suspects. It’s the Minnesota-based agribusiness giant Cargill.

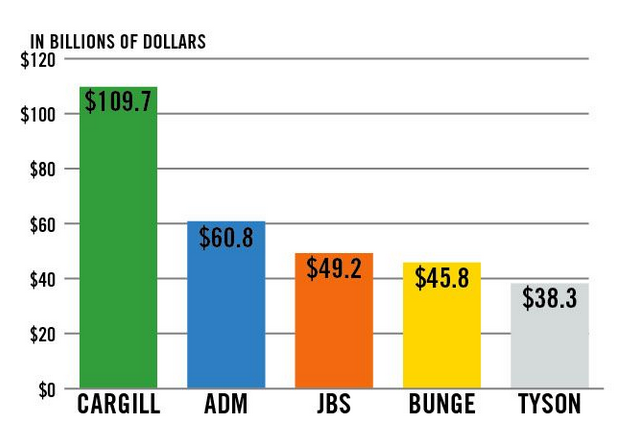

Cargill is America’s largest privately-owned company, surpassing the second place Koch Brothers by billions of dollars in annual revenues. Cargill is the corporate behemoth at the nexus of the global industrial agriculture system, a system that it has designed to convert large swaths of the planet into chemically dependent industrial scale monocultures to produce cheap meat, palm oil, and chocolate.

The political constraints that might have once limited its power have essentially disappeared, thanks to the rise of extremist anti-environment Presidents in both Brazil and the United States. In other parts of the world, like Indonesia and West Africa, Cargill continues to take advantage of fragile or corrupt governments to acquire vast quantities of palm oil, cocoa, and other raw materials without much regard to the manner in which it was produced.

Cargill has demonstrated the ability to do both good and ill on a grand scale. But the environmental protections and climate leadership from governments that may have once held the company’s worst instincts in check are now in retreat.

Throughout its history, Cargill has exhibited a disturbing and repetitive pattern of deception and destruction. As this report details, its practices have ranged from violating trade embargoes and price fixing, to ignoring health codes and creating markets for goods produced with child and forced labor. Under pressure, Cargill has reformed its practices in many areas — which shows that it can change when it wants to. But contrary to its view of itself as a leader, it usually comes in dead last. It has remained a laggard across multiple industries, trailing peers like Louis Dreyfus and Wilmar.

Shortly after incorporating under its present name 80 years ago, Cargill was thrown out of the nation’s largest futures and options exchange for trying to corner the market on corn. Decades later, in 2017, Cargill was fined $10 million by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission for years of deliberately misreporting its trade values — by up to 90% — in order to defraud both the government and its trading partners.1 As this report was going to press, David Dines, the executive who created and oversaw the department responsible for these violations at Cargill, was promoted to the position of Chief Financial Officer.2 In 2018, Cargill was responsible for the distribution of more than 70 tons of contaminated beef to supermarkets.3 In between, the company has plundered the planet and shortchanged its workers and farmers, all while generating enough wealth to create more billionaires than in any other family in the world.4

Cargill today has greater influence than even many governments over the fate of our world. Companies like Cargill — and business partners and customers like Ahold Delhaize (Stop & Shop, Giant, Food Lion, and Hannafords), McDonald’s, and Sysco that sell their products to consumers — bear significant responsibility for the planet’s severe environmental crisis.

A Clear and Present Danger

Nowhere is Cargill’s pattern of deception and destruction more apparent than in its participation in the destruction of the “the lungs of the planet,” the world’s forests. Despite repeated and highly publicized promises to the contrary, Cargill has continued to bulldoze ancient ecosystems as it can within the bounds of the law — and, too often, outside of those bounds as well.

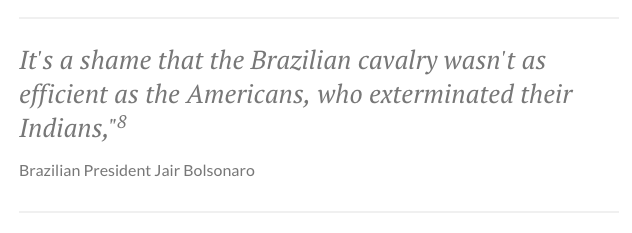

With the election of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro — who has promised to open Indigenous lands and other protected areas to unrestricted exploitation — Cargill presents a clear and present danger to some of the most vital ecosystems on Earth. Like any other nation, Brazil has the right to the leaders it chooses. But, so too do the customers of Cargill have a right to insist on corporate policies that protect the environment and human rights. Those customers must act decisively and quickly.

If Cargill’s top customers — including Ahold Delhaize, McDonalds, WalMart, Sysco and others — are serious about their commitments to sustainability and human rights, they will cut their ties with Cargill, or risk being complicit in one of the greatest environmental and human rights crime sprees in history.

Brazil: A Proud Legacy at Risk

Until now, Brazil has been a leader in the battle against climate change. Since the mid-2000s, the nation has been committed to ambitious programs to curb deforestation in the Amazon. Brazil impressively cut deforestation by two-thirds from its peak, all while doubling its agricultural production by focusing expansion on degraded lands.

But the election of Jair Bolsonaro as President in 2018 could end that worthy legacy. Bolsonaro has called for violence against Brazil’s gay and lesbian community, and jailing or banishing all political critics. He has praised the military dictatorship that preceded Brazil’s current democracy. And, part and parcel of his extreme agenda, he has promised to promote logging, agriculture, and mining throughout Brazil’s rainforests, savannahs, and Indigenous lands.

According to Brazilian researcher Paulo Artaxo, a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “We may face an unprecedented environmental disaster in the next four years.”10

Bolsonaro has said that Brazil has “too many protected areas” that “stand in the way of development,” and that policing of deforestation has gone too far. He has told agribusiness companies that he will roll back existing laws and give industry free rein.11 He has pledged to eviscerate Brazil’s environment agency, Ibama, to remove restrictions on the industrialized clearing of the Amazon, and to pave a highway through the rainforest.12 He has long supported opening up protected Indigenous areas to agricultural and commercial use,13 and has promised that as president he would not “give an inch to the Indigenous reservations.”14

Since taking office, Bolsonaro has abolished Brazil’s Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, slashed the budget of IBAMA Brazil’s environmental protection agency. Not only has the government signaled its intentions to stop enforcing existing environmental laws, it has even created a new agency to review and forgive previous violations. Unsurprisingly, deforestation of the Amazon has risen to its highest level in a decade.

According to the country’s previous environment minister, Edson Duarte, “The increase of deforestation will be immediate. I am afraid of a gold rush to see who arrives first. They will know that, if they occupy illegally, the authorities will be complacent and will grant concordance. They will be certain that nobody will bother them.”16

Many Brazilians do not support this part of Bolsonaro’s agenda. A coalition of more than 180 businesses and civil society organizations called Coalizão Brasil Clima, Florestas e Agricultura has courageously — and successfully — called on the new administration not to leave the Paris Agreement or destroy the Ministry of Environment.

Cargill has stated its support for this coalition.17 Cargill’s customers must ensure that this is not just another one of Cargill’s numerous empty promises.

The Business of Destroying the Environment

In 2014 at the United Nations Climate Summit, Cargill CEO David MacLennan stood beside UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon to pledge action on climate change by eliminating deforestation from its supply chain.

“I am proud to announce today that Cargill will take practical measures to protect forests across our agricultural supply chains around the world,” said MacLennan, as he joined 150 countries, businesses, and civil society organizations to announce their support for the New York Declaration that sets a goal of dramatically reducing global deforestation.20

Because of Cargill’s size and impact, its signing the pledge was hailed as having the potential to dramatically decrease deforestation, curb climate change, and protect communities around the world.

But after the summit ended and applause died down, Cargill dropped the ball. And then they stomped on it.

Since the signing of the Declaration, Cargill has continued to drive the destruction of pristine landscapes, remaining one of the worst actors on the world stage, and one of the greatest threats to native ecosystems across the globe.

For years, Mighty Earth, other conservation organizations, and Cargill’s largest customers have tried to hold Cargill accountable for delivering on its promises to reform to no avail. Now, five years after Cargill’s pledge, and less than one year left in the timeline to end deforestation in its supply chain, comes the dawning of a potential anti-environment free for-all in Brazil. It is time for those customers to stop aiding and abetting Cargill by buying and selling their products.

More than one million square kilometers of the planet have been cleared of their natural vegetation to grow soy, one of the primary ingredients of animal feed used to raise meat. More than three quarters of the world’s soy is used to feed livestock.21

Deforestation for soy production accelerates climate change through the release of carbon, destroys wildlife habitat, and disrupts hydrological cycles, limiting the availability of water.

Across the South American frontier, Mighty Earth has tracked Cargill’s footprint. Our 2017 report “The Ultimate Mystery Meat” investigated 28 different locations across 3,000 km producing soy in Brazil and Bolivia. It showed that Cargill was one of the two largest customers of industrial scale deforestation.

In addition to their role in creating a market for deforestation-based soy, we found that Cargill finances land-clearing operations deep in virgin forest, building silos and roads, then buying and shipping grain to the US, China, and Europe to feed chickens, pigs, and cows.

After our report was covered in publications around the world, including The New York Times, The Guardian, CTV, Le Monde and others, major consumer companies, investors, and governments urged Cargill to uphold its commitments to end deforestation in Latin America.

Months later, we conducted satellite monitoring of the sites we had originally visited. Given the scrutiny to which Cargill had been exposed, and their commitments to their customers, we assumed that they would launch intensive efforts to stop deforestation at least in these locations.

In contrast, we found that Cargill was still driving deforestation at some of the same sites we had first visited, despite the scrutiny. Between Cargill and their doppelganger Bunge, they had cleared the equivalent of 10,000 foortball fields for soy.

Indigenous Peoples who depend on forests have been forced off of their traditional lands, had their land encroached upon by soy plantations, have experienced sharp increases in cancer, birth defects, miscarriages, and other illnesses linked to pesticides and herbicides used to grow soy.

Cargill’s own history with soy shows that deforestation is neither necessary nor inevitable. In the one place where Cargill was forced to change, the company managed to both protect ecosystems and grow its businesses.

In 2006, following a major campaign by Greenpeace and others, Cargill and its customer McDonald’s agreed to a moratorium on clearing the Brazilian Amazon for soy. In the two years before the agreement, nearly a third of the new soy plantations in the Brazilian Amazon came from forest destruction. After the agreement, that number dropped to around one percent.

Meanwhile, the soy industry still managed to grow at a tremendous pace. Even as deforestation plummeted, the area planted with soy in the Brazilian Amazon more than tripled.

Expansion without deforestation is possible. When forced to, Cargill and others shifted their focus onto previously deforested lands, and more efficient agricultural practices.

If only a small portion of South America’s previously deforested land were developed for agriculture, it would provide ample space to achieve both agricultural expansion and ecological restoration.22

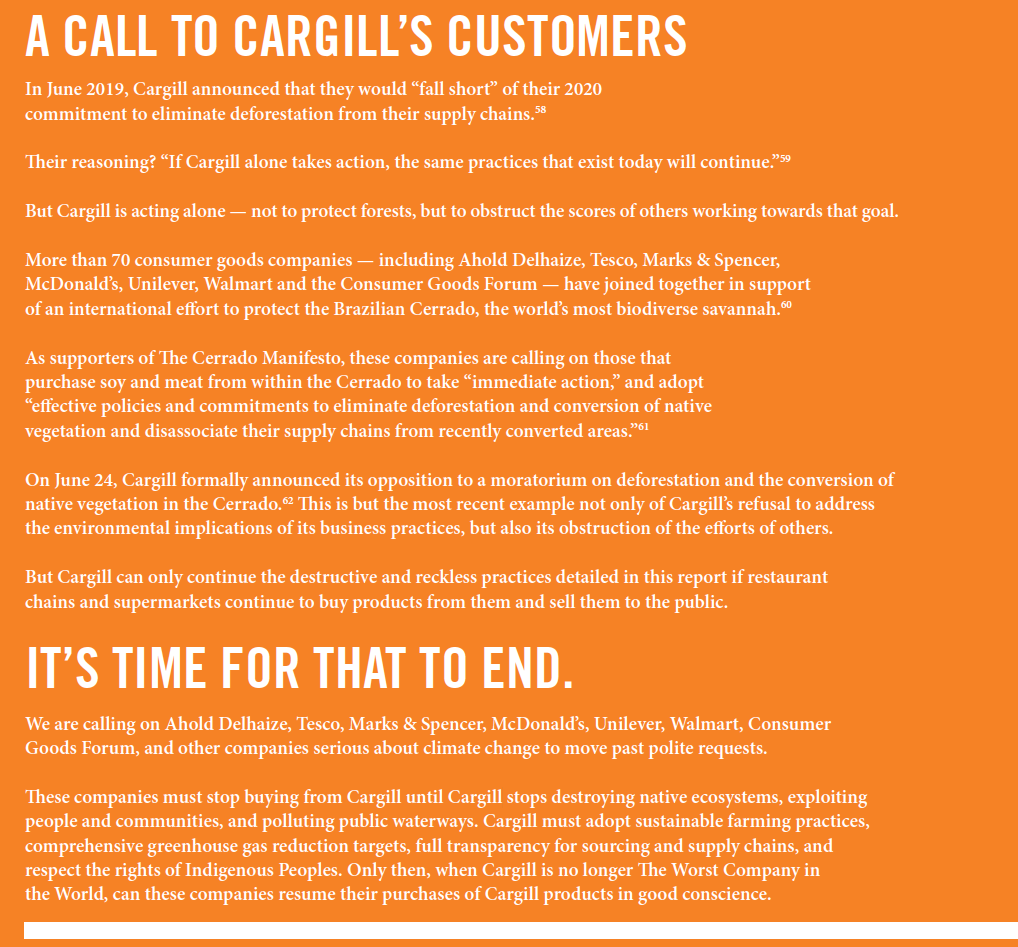

Many of Cargill’s customers, including Unilever, Tesco, McDonald’s, Carrefour, Kellogg’s, Sainsbury’s, Mars, Petcare, Ahold Delhaize, Dunkin’ Brands, and Nestle have called for extending this success from the Brazilian Amazon to other ecosystems.23 Cargill competitors Louis Drefyus, COFCO, and Wilmar have also advocated for this expansion. But Cargill has refused, and instead used its influence with trade associations to block its more responsible competitors from expanding these protections.

Spotlight on the Cerrado

Cargill’s successful Moratorium on Deforestation for Soy unfortunately applies only to the portions of the Amazon within Brazil. Outside of the Amazon, Cargill does not protect any rainforest in the eight other Amazonian countries. Nor does it protect other forests and prairies outside Brazil like the Gran Chaco of Argentina, and Paraguay. And finally, it does not protect critical ecological areas within Brazil but outside the Amazon, like the magnificent Brazilian Cerrado.

Brazil’s Cerrado is the most biologically rich savanna in the world. Roughly the size of England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain combined, it is home to one out of every twenty species on Earth, including the giant anteater, giant armadillo, jaguar, maned wolf, and hundreds of bird species — as well as more than 10,000 species of plants, nearly half of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

Known as an “upside-down forest” for its small trees with deep roots, the Cerrado is the source of half of Brazil’s water and has enormous carbon storage capacity.

But over the past decade, more than 4,000 square miles per year have been converted to plantations — twice the rate seen in the 1990s.23 Now, less than half of the Cerrado remains intact, and only 3% is permanently protected.

When tropical forests are cut down and burned, their stored carbon is immediately released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, generating one-tenth of all global warming emissions.24

There are more than a billion acres of already-degraded land in Latin America that could be used to expand agriculture, and there is no reason other than corporate inertia to continue to destroy these priceless landscapes.25

Cargill’s largest customers as well as government officials and civil society have asked them and other soy traders to expand the moratorium, protect these critical areas, and focus expansion onto already degraded lands.26 Cargill refuses.

The Destruction of the Gran Chaco

The Gran Chaco is a 110 million hectare ecosystem spanning Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay. It is one of the largest remaining continuous tracts of native vegetation in South America, second in size only to the Amazon rainforest.

These forests are home to vibrant communities of Indigenous Peoples, including the Ayoreo, Chamacoco, Enxet, Guarayo, Maka’a, Manjuy, Mocoví, Nandeva, Nivakle, Toba Qom, and Wichi, who have depended on and coexisted with the Chaco forest for millennia.

Once the impenetrable stronghold of creatures like the screaming hairy armadillo, the jaguar, and the giant anteater, Cargill has infiltrated these frontiers, bulldozing and burning to make way for vast fields of genetically modified soy.

In 2018, a Mighty Earth field team visited soy plantations across the Gran Chaco ecosystem and documented extensive destruction of natural ecosystems, some of it illegal and some under the guise of legality. We tracked the soy from recently cleared forests to the ports where Cargill ships it around the world.

The tragedy of the destruction we documented is that it is entirely avoidable. While meat is inherently resource-intensive to produce, it does not require the destruction of native ecosystems. Latin America contains an area of previously degraded land larger than half the continental United States where soy and cattle can be raised without threatening native ecosystems. Technical experts who successfully designed the system that virtually eliminated deforestation for soy in the Brazilian Amazon estimate that extending forest monitoring to other soy-growing regions in Latin America would cost less than a million dollars a year, a tiny fraction of Cargill’s annual profits.

Human Rights Violations and Violence Against Indigenous Communities

Many indigenous communities live in forests and rely on them for food, water, shelter, and their cultural survival. Soy producers, ranchers, and illegal logging interests have often used violence to displace Indigenous People from their ancestral land.

Mighty Earth’s investigative teams have visited Indigenous communities whose traditional territories have been cut down and transformed into soy fields whose crops are exported overseas. Workers on these lands say they sell to Cargill. Cargill denies the allegations.

A village leader described to our team the fear his community experiences when planes fly overhead and spray pesticides for soy just a few hundred meters from the village, and of several children dying from drinking water from a discarded pesticide container brought back from a nearby soy field.

Another Indigenous community was invaded in 2014 by 50 armed security guards from a neighboring plantation intended to force them to leave the area. According to newspapers in accounts corroborated by community testimony, the armed security guards smashed down doors and invaded houses, assaulted the adults and children, and kicked pregnant women — some of whom lost their babies. Thirty-two members of the community were hurt. Three guards and seven Indigenous People were hit by gunshots. One guard was killed.

A community’s leader told us that the plantation keeps accusing them of trespassing on their own traditional lands, and that his people live in constant fear that the private security officers will come back. He said their rivers are so polluted by pesticides that the fish they depend upon are dying off, and that opportunities for traditional hunting have nearly disappeared.

Cargill is one of just three companies — along with Olam and Barry Callebaut — that controls more than half of the global trade in cocoa, the raw material for chocolate.28

In 2017, Mighty Earth investigations traced cocoa from illegal operations in national parks, through middlemen, to these traders, who then sold it onto Europe and the United States where the world’s confectionary companies made it into chocolate.

Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are the world’s two largest cocoa-producing countries, and in both, the market for cocoa has been the primary driver of forest destruction. Chimpanzees and other wildlife populations have been devastated by the conversion of forests to cocoa farms. In Côte d’Ivoire, as few as 400 elephants remain from an original population in the tens of thousands.

Our investigation found that, for years, Cargill helped to drive the destruction of these countries’ forests to grow cheap cocoa — buying cocoa grown through the illegal clearing of protected forests and national parks as a standard practice. In Côte d’Ivoire, an estimated 30% of the cocoa came from inside national parks and other protected areas.

In more than twenty of these national parks and protected areas, 90% or more of the land mass has already been converted to cocoa. Between 2001 and 2014, Ghana lost 7,000 square kilometers of forest, or about 10 percent of its entire tree cover, including a quarter of a million acres of protected areas. Approximately one quarter of that deforestation was connected to the chocolate industry.29

Cargill chose to buy its cocoa without scrutiny of its origins. They then sold that cocoa to the world’s leading chocolate companies, making millions of consumers unknowingly complicit in the destruction of West Africa’s parks, forests, elephants, and chimpanzees.

In 2017, Cargill joined other chocolate and cocoa companies and the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana in the Cocoa and Forests Initiative, committing themselves to immediately end sourcing from national parks and protected areas, to restore forests, and to shift to more responsible practices. Mighty Earth hailed the announcement as a positive step that finally provided some hope for the battered wildlife populations of West Africa, and a more sustainable future for the impoverished cocoa farmers who supply Cargill.

But a year later, we went back to investigate, and found that in many places, deforestation had actually increased since Cargill announced its commitment — casting into doubt whether Cargill’s pledge was anything more than the latest in a long line of commitments that it makes to great fanfare and then immediately ignores.

Cargill’s Open-Air Sweatshops

As of 2015, an estimated 2.12 million West African children were still engaged in harvesting.30 Almost 96% of these child laborers in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire were involved in hazardous work. Cargill has kicked the can down the road for two decades. Its current low-ambition pledge is to reduce — not eradicate — the “worst forms” of child labor in cocoa by 70% by 2020.31

In July 2005, the International Labor Rights Fund (ILRF) filed suit against Cargill on behalf of Malian children who were trafficked from Mali into Côte d’Ivoire and forced to work twelve to fourteen hours a day with no pay, little food and sleep, and frequent beatings.

According to the ILRF, Cargill “ignored repeated and well-documented warnings over the past several years that the farms they were using to grow cocoa employed child slave laborers.”

The lawsuit charges that, for years, Cargill knowingly purchased cocoa harvested by child slaves and provided funds, supplies, training and other assistance to the plantations in Côte d’Ivoire that they knew were using child slaves.

In October 2018, a three-judge panel rejected Cargill and co-defendant Nestlé’s claims that they could not be charged for the enslaving of children outside of the country. The Court ruled that the case can proceed, as the giant corporations are charged to have aided, abetted, and profited from child slavery from their corporate offices in the United States.

The ILRF legal team will soon be filing additional charges against Cargill and others for knowingly benefitting from the trafficking of children into slavery to harvest cocoa.32

As one of the world’s largest importers and exporters of palm oil, Cargill is one of the companies that has helped drive the alarming destruction of tropical rainforest and carbon-rich peatlands, contributing significantly to climate change, the deaths of more than 100,000 orangutans, the loss of Indigenous community lands and livelihoods, and the mistreatment of workers.

Cargill consistently describes itself as a “leader” in the sector — but time and again, all over the world, Cargill keeps coming in last place. It’s hard not to see a pattern.

The company has devastated the traditional territories of Indigenous communities33 and purchased palm oil from rainforest destroyers who illegally burned rainforests and trafficked in slaves and child labor.34 Executives from one of its suppliers were fined and jailed for causing forest fires35 — contributing to a toxic haze from fires lit by palm oil and timber companies that have cut short the lives of more than 100,000 people across Southeast Asia.36

In 2016, the massive, Malaysian-based palm oil conglomerate IOI was caught illegally laying waste to protected tropical rainforests, draining and digging up carbon-rich peatlands, and exploiting local communities and workers.37 And they have encroached on Indigenous Sarawak for nearly a decade without consent.38 As a result, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) suspended IOI’s sustainability certification and 26 companies canceled their contracts with IOI, including Unilever, Kellogg Company, Mars, Hershey’s, Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, Yum! Brands, and Nestlé.39 Only months later, after repeated and growing continued public pressure, did Cargill join the rest of the business community in severing its ties. Cargill has since resumed sourcing from IOI.40

Similarly, in 2015, the Guatemalan palm oil company Reforestadora de Palmas del Petén, S.A (REPSA) was identified as likely responsible for massive contamination of one of Guatemala’s largest rivers, resulting in a massive fish kill of more than one hundred and fifty tons of fish, devastating over a hundred communities that depend on the river. Following a lawsuit brought by a local community group, a Guatemalan court found REPSA guilty of “ecocide” and ordered them to suspend operations.

After the ruling, Commission spokesperson and Indigenous professor Rigoberto Lima Choc was murdered, three other members of the group were kidnapped, and REPSA forced the ruling to be overturned. Not until after years of pressure by organizations in the US and Latin America environmental and human rights organizations, and the arrests for bribery and tax fraud of three of REPSA’s top executives did Cargill finally suspended their contract.41

Cargill still does not have a comprehensive approach to prevent and address the growing intimidation and violence of human rights defenders that is widely prevalent in its supply chains for palm and other commodities.42

Producing meat has a larger environmental impact than almost any other human activity.

Cargill is the second-largest feed beef processor in North America and the largest supplier of ground beef in the world.44

Feeding and raising meat consumes more land and freshwater than any other industry, and the industry’s waste byproducts rank among the top sources of pollution around the world. Many of these impacts are concentrated in the United States, where factory farming has its stronghold, but are spreading rapidly to other parts of the world. The meat industry can dramatically reduce many of these impacts through better farming practices for sourcing feed and raising livestock, such as cover cropping, using rotationally raised small grains in feed, fertilizer management, conservation of native vegetation, feed improvements, and centralized manure processing. Major meat producers like Cargill that have consolidated control over the market have the leverage to dramatically improve their environmental impact. Yet to date they have done little — ignoring public concerns and allowing the environmentally damaging practices for feeding and raising meat to expand largely unchecked.

And for the past three years, ten of Cargill’s facilities have been out of compliance with EPA emissions regulations every single quarter.45 Just as it is trying to take advantage of political rollbacks to environmental enforcement in Brazil, Cargill seems to be trying to take advantage of the Trump administration’s efforts to scale back environmental enforcement in the United States.

Runoff pollution from corn and soybeans, of which Cargill is one of the nation’s top processors, is responsible for more than half of the nitrogen and a quarter of the phosphorus that finds its way into the Gulf Mexico, causing an annual dead zone from algal blooms which in 2017 grew to the size of New Jersey. While Cargill has adopted policies for reducing the environmental impacts of its commodity crops abroad, it has adopted none for those supply chains in the U.S.

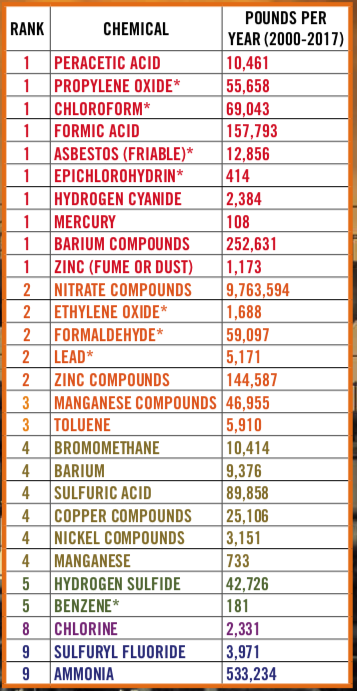

Cargill is one of the top ten food industry polluters in the U.S. in the food industry, for the following toxic chemicals:

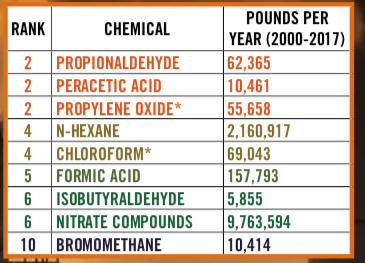

Cargill is one of the top ten food industry polluters in the U.S. of all companies for the following toxic chemicals:

Negligent, Not Inevitable

In a 2009 Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation,46 The New YorkTimes found a pattern of negligence and recalcitrance on the part of Cargill that led to a disastrous outbreak of E. coli O157:H7, a particularly virulent strain of bacteria found in animal feces.

Investigators for the Times found that Cargill hamburger patties tainted with E. coli had been sold at Sam’s Club labeled “American Chef ’s Selection Angus Beef Patties.”

According to the Times, the hamburgers, whose ingredients were listed solely as “beef,” “were made from a mix of slaughterhouse trimmings and a mash-like product derived from scraps that were ground together at a plant in Wisconsin. The ingredients came from slaughterhouses in Nebraska, Texas and Uruguay, and from a South Dakota company that processes fatty trimmings and treats them with ammonia to kill bacteria.”47

Using a combination of sources rather than whole cuts of meat saves Cargill about 25 percent in costs, but the lowgrade ingredients are cut from areas of the cow that are more likely to have had contact with feces, which carries E. coli.

The Times discovered that in the weeks leading up to the 2007 outbreak, federal inspectors had repeatedly found Cargill violating its own safety procedures in handling ground beef.48

Cargill’s Partners in Crime

The Dutch company Ahold Delhaize operates 6,500 stores under 21 local brands in 11 countries. Construction is set to begin on a 200,000 square- foot facility Cargill run facility in North Kingstown, R.I., to provide Ahold Delhaize-owned stores with beef, ground pork and prepared meats.51

Ahold is very active in calling for responsible food policies. They joined other companies as signatories of The New York Declaration on Forests calling for all companies to end deforestation in their supply chains by 2020. They are a part of “Protein Challenge 2040,” a coalition of international retailers, food manufacturers and non-governmental organizations with the stated goal of working toward the sustainable production and consumption of protein.53 They were one of the original signatories to the 2018 Statement of Support for the Cerrado Manifesto, a document that calls on Cargill and other companies to cease the destruction of this biodiversity hotspot. And they have a target in place for 2020 that requires the certification of all of the South American soy in the supply chain of its store-branded meat products. In addition, they have called for standards on human rights consistent with the UN Global Compact, and support the Consumer Good’s Forum’s resolution opposing forced labor.54

In meetings and conversations with Mighty Earth going back years, Ahold Delhaize staff have acknowledged the issues with Cargill meat and animal feed, and repeatedly pledged to act. But despite all this rhetoric, and their deep knowledge of Cargill’s environmental and social offences, Ahold Delhaize announced in May of 2018 that rather than moving away from Cargill, they were going to draw even closer.

They launched a major joint venture with Cargill for a new 200,000-square-foot “Infinity Meat Solutions” packaging plant to provide Ahold Delhaize’s US stores with beef, ground beef, pork and “creative prepared meats for meal solutions”.55 In clear contrast with its words, Ahold Delhaize is rewarding Cargill with a massive market, making Giant, Stop & Shop, Hannaford, and Food Lion’s customers unknowingly and unnecessarily complicit in Cargill’s misdeeds.

Cargill’s Enablers

McDonald’s is probably Cargill’s largest and most important customer. McDonald’s restaurants are essentially storefronts for Cargill. Cargill not only provides chicken and beef to McDonald’s, they prepare and freeze the burgers and McNuggets, which McDonald’s simply reheats and serves.49

Burger King’s practice of selling meat linked to Cargill and other forest destroyers has earned the fast food giant a ‘zero’ on the Union of Concerned Scientists deforestation scorecard.Burger King has asked Cargill to stop destroying forests in their supply chain…by 2030.50

With 55 billion dollars in annual revenue, Sysco Inc. is the world’s largest distributor of food products to restaurants, healthcare facilities, universities, hotels and inns. Despite claiming that they will, “protect the planet by advancing sustain- able agriculture practices, reducing our carbon footprint and diverting waste from landfill, in order to protect and preserve the environment for future generations,” they have honored Cargill as their most valued supplier of pork and beef.52

Cargill’s competitors have shown the world that a different path is possible. The Louis Dreyfus Company, one of the four largest traders in soy from Latin America, has recognized the urgent need to protect native ecosystems and communities. In a new policy, the company announced that it would no longer buy soy from producers who destroyed native ecosystems or grabbed land from Indigenous communities. Given the widespread availability of already degraded lands, Louis Dreyfus recognized that it could continue to grow without destruction.56 Wilmar International, Asia’s leading agribusiness and one of the world’s leading soy buyers has supported similar change, and in January 2019, COFCO, the largest food processor, market- er and trader in China, said it was an “ethical imperative” to immediately move soy production off of intact forests.57 Meanwhile, Cargill has kept the bulldozers running. Louis Dreyfus’ policy gives companies like Ahold Delhaize and other Cargill enablers an alternative for their soy purchases.

Conclusion

2018 brought a drumbeat of troubling news, with the United Nations and the US Government reporting foreboding warnings for the earth’s climate and its inhabitants.

First, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that we need “rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure (including transport and buildings), and industrial systems” to avoid catastrophic impacts from global warming. A few weeks later, the U.S. government’s Fourth National Climate Assessment in November of 2018 said that, “without substantial and sustained global mitigation and regional adaptation efforts, climate change is expected to cause growing losses to American infrastructure and property and impede the rate of economic growth over this century.”

We still have a choice about the future we want, but we may be the last generation that does. A better world is possible, but only with immediate and substantive action.

While both the reports and the media focus primarily on the role of government, for the most part it is not governments that do the polluting or deforesting — it is large industrial and multinational companies like Cargill.

Whether or not governments do their job doesn’t mean the job can’t be done. Some of the world’s greatest environmental successes have been achieved by companies, acting either from their own sense of responsibility, or spurred by customers, investors, and society more broadly. Cargill itself and other soy traders have demonstrated this by protecting part of the Amazon because their customers demanded that they to do so.

But Cargill refuses to expand these protections to other landscapes, even going as far as to publicly announce its opposition to a moratorium on the destruction of Brazil’s priceless and threatened Cerrado, supported by more than seventy consumer goods companies. This is a slap in the face to Ahold Delhaize, McDonald’s, and others that have repeatedly called on Cargill to build on the extraordinary success of the Amazon Soy Moratorium. If these companies are serious about their own sustainability commitments, they’ve got to go beyond polite calls and shift their purchases to more responsible suppliers.

MAR. 2, 2000 – EDITORIAL/OPINIONS

———————————————————————————————————————— Cargill: Our taxes, global destruction

Minnetonka-based Cargill is often noted as the world’s largest private corporation, with reported annual sales of over $50 billion and operations at any given time in an average of 70 countries. The “Lake Office” of Cargill is a 63-room replica of a French chateau; the chairman’s office is part of what was once the chateau’s master-bedroom suite.

A family empire, the Cargills and the MacMillans control about 85 percent of the stock. Not only the largest grain trader in the world, with over 20 percent of the market, Cargill dominates another 12 sectors, including destructive speculative finance, according to “Invisible Giant: Cargill and its Transnational Strategies,” by Brewster Kneen.

Taking advantage of the capitalist speculative collapse of 1873, Cargill quickly bought up grain elevators. After vast cooperation with the state-sponsored railroad robber barons, central grain terminals averaged extremely high annual returns on investments of 30 to 40 percent between 1883 and 1889. Cargill hired a Chase Bank vice president to secretly help the corporation through the Depression, writes Dan Morgan in “Merchants of Grain.”

“There are only a few processing firms,” and “these firms receive a disproportionate share of the economic benefits from the food system,” states William D. Heffernan, professor of rural sociology at the University of Missouri. Details of Cargill’s price manipulations at the expense of farmers worldwide was documented in the classic study, “Food First: Beyond the Myth of Scarcity” by Frances Moore Lappe and Joseph Collins. They report that Cargill has had a history of receiving elite government price information that should be told to U.S. farmers.

That secrecy, along with tax-subsidized market control, enables Cargill to buy from U.S. farmers at extremely low prices and then sell abroad to nations pressured under the same destructive elite corporate control. See the Institute for Food and Development Policy’s Web Site at http://www.foodfirst.org….

Between 1985 and 1992, the legal entity called Cargill received $800.4 million in tax subsidies via the Export Enhancement Program, a continuation of the infamous “Food for Peace” policy, writes Kneen. Promoted by Hubert H. Humphrey and instituted as PL 480, food became a Cold War tool, i.e. “for Peace.” If we can induce people to “become dependent on us for food,” then “what is a more powerful weapon than food and fiber?” Humphrey declared, according to “Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies” by Noam Chomsky.

Actually, most of the nation recipients of tax-subsidized Cargill food dumping were, and are, net exporters of food already — policies imposed by colonial trading patterns. The food (for Peace) has been bought cheaply by neocolonial regimes, and then sold at a huge discount on the local market — in Somalia, for example, at one-sixth of the local prices. Many examples of these misguided policies can be found in “Betraying the National Interest: How US Foreign AID Threatens Global Security by Undermining the Political and Economic Stability of the Third World,” by Frances Moore Lappe, et al.

Cargill’s undercutting wipes out the local farmers’ self-reliance, while the revenues (going to the elite) are tied to required purchases of U.S. weapons, writes Chomsky, citing “The Soft War” by Tom Barry, 1988. But the main beneficiary of “Food for Peace” has been Cargill. Keen writes, “From 1954 to 1963, just for storing and transporting P.L. 480 commodities, the heavily subsidized giant Cargill made $1 billion.”

Indian lawyer N.J. Nanjundaswamy reports that a Cargill motto is, “One who controls the seed, controls the farmer, and one who controls the food trade, controls the nation.” Yudof’s recently stated support of federal foreign policy Title XII is another public promotion of the University of Minnesota-Cargill partnership’s raiding of sustainable agricultural cultures.

Cargill is such a damaging threat that in Dec. 1992, 500,000 peasants marched against corporate-controlled trade, and the irate farmers ransacked Cargill’s operations. Fifty people were arrested at the partially completed — and subsequently destroyed — seed-processing plant in Bellary, India. In 1996, 1,000 Indian farmers gathered at Cargill’s office and destroyed Cargill’s records. For more, see http://www.endgame.org...

Cargill has been doing bio-piracy, stealing traditional products. For instance, it used Basmati, a rice from India, as its trade name, and the company continues to be one of the main promoters of corporate-driven intellectual property rights. The U.S. Trade Act, Special 301 Clause, allows the United States to take unilateral action against any country that does not open its market to U.S. corporations.

The United States, for example, has threatened to use trade sanctions against Thailand for its attempt to protect biodiversity. A bill that has been before parliament in India and promoted by Cargill, “takes away all the farmers’ rights, which they have enjoyed for generations — they will no longer be able to produce new varieties of seed or trade seed amongst themselves,” writes Nanjundaswamy.

The research center, Rural Advancement Foundation International, found that “fifteen African states, among them some of the poorest countries in the world, are under pressure to sign away the right of more than 20 million small-holder farmers to save and exchange crop seed. The decision to abandon Africa’s 12,000-year tradition of seed-saving will be finalized at a meeting in the Central African Republic. The 15 governments have been told to adopt draconian intellectual property legislation for plant varieties in order to conform to a provision in the World Trade Organization.”

Cargill, with extensive funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development, is also destroying the world’s largest wetland — the Pantanal, in South America — in order to dredge a channel that’s designed for convoys of up to 16 soybean- and soymeal-carrying barges, according to the Institute on Food and Development Policy.

Cargill has been on the Council of Economic Priorities’ list of worst environmental offenders. Mother Jones magazine and Earth Island Journal report that Cargill is responsible for 2,000 OSHA violations, a 40,000-gallon spill of phosphoric solution into Florida’s Alafia River, poor air pollution compliance and record-high releases of toxic waste.

With help from the Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy, located at http://www.poclad.org…, states have recently begun to respond to citizen pressure and revoke corporate charters. The assets of Cargill should be revoked, allowing the citizens of the United States to give farmers the benefits of fair trade instead of Cargill’s secretive policy of tax-subsidized global destruction.