Politico: The Short, Unhappy Life of a Libertarian Paradise

By Caleb Hannan | July/August 2017

The residents of Colorado Springs undertook a radical experiment in government. Here’s what they got.

Colorado Springs has always leaned hard on its reputation for natural beauty. An hour’s drive south of Denver, it sits at the base of the Rocky Mountains’ southern range and features two of the state’s top tourist destinations: the ancient sandstone rock formations known as Garden of the Gods, and Pikes Peak, the 14,000-foot summit visible from nearly every street corner. It’s also a staunchly Republican city—headquarters of the politically active Christian group Focus on the Family (Colorado Springs is nicknamed “the Evangelical Vatican”) and the fourth most conservative city in America, according to a recent study. It’s a right-wing counterweight to liberal Boulder, just a couple of hours north, along the Front Range.

It was its jut-jawed conservatism that not that long ago made the city’s local government a brief national fixation. During the recession, like nearly every other city in America, Colorado Springs’ revenue—heavily dependent on sales tax—plunged. Faced with massive shortfalls, the city’s leaders began slashing. Gone were weekend bus service and nine buses.

Out went some police officers along with three of the department’s helicopters, which were auctioned online. Trash cans vanished from city parks, because when you cut 75 percent of the parks’ budget, one of the things you lose is someone to empty the garbage. For a city that was founded when a wealthy industrialist planted 10,000 trees on a shadeless prairie, the suddenly sparse watering of the city’s grassy lawns was a profound and dire statement of retreat.

To fill a $28 million budget hole, Colorado Springs’ political leaders—who until that point might have been described by most voters as fiscal conservatives—proposed tripling property taxes. Nearly two-thirds of voters said no. In response, city officials (some would say almost petulantly) turned off one out of every three street lights. That’s when people started paying attention to a city that seemed to be conducting a real-time experiment in fiscal self-starvation. But that was just the prelude. The city wasn’t content simply to reject a tax increase. Voters wanted something genuinely different, so a little more than a year later, they elected a real estate entrepreneur as mayor who promised a radical break from politics as usual.

For a city, like the country at large, that was hurting economically, Steve Bach seemed like a man with an answer. What he promised sounded radically simple: Wasteful government is the root of the pain, and if you just run government like the best businesses, the pain will go away. Easy. Because he had never held office and because he actually had been a successful entrepreneur, people were inclined to believe he really could reinvent the way a city was governed.

The city’s experiment was fascinating because it offered a chance to observe some of the most extreme conservative principles in action in a real-world laboratory. Producers from “60 Minutes” flew out to talk with the town’s leaders. The New York Times found a woman in a dark trailer park pawning her flat screen TV to buy a shotgun for protection. “This American Life” did a segment portraying Springs citizens as the ultimate anti-tax zealots, willing to pay $125 in a new “Adopt a Streetlight” program to illuminate their own neighborhoods, but not willing to spend the same to do so for the entire city. “I’ll take care of mine” was the gist of what one council member heard from a resident when she confronted him with this fact.

That’s where Colorado Springs was frozen in the consciousness of the country—a city determined to redefine the role of government, led by a sharp-elbowed businessman who didn’t care whom he offended along the way (not unlike a certain president). But it has been five years since “This American Life” packed up its mics. A lot has changed in that time, not least of which is that the local economy, which nearly drowned the city like a concrete block tied around its balance sheet, is buoyant once again. Sales tax revenue has made the books plump with surplus. Enough to turn those famous streetlights back on. Seven years after the experiment began, the verdict is in—and it’s not at all what its architects planned.

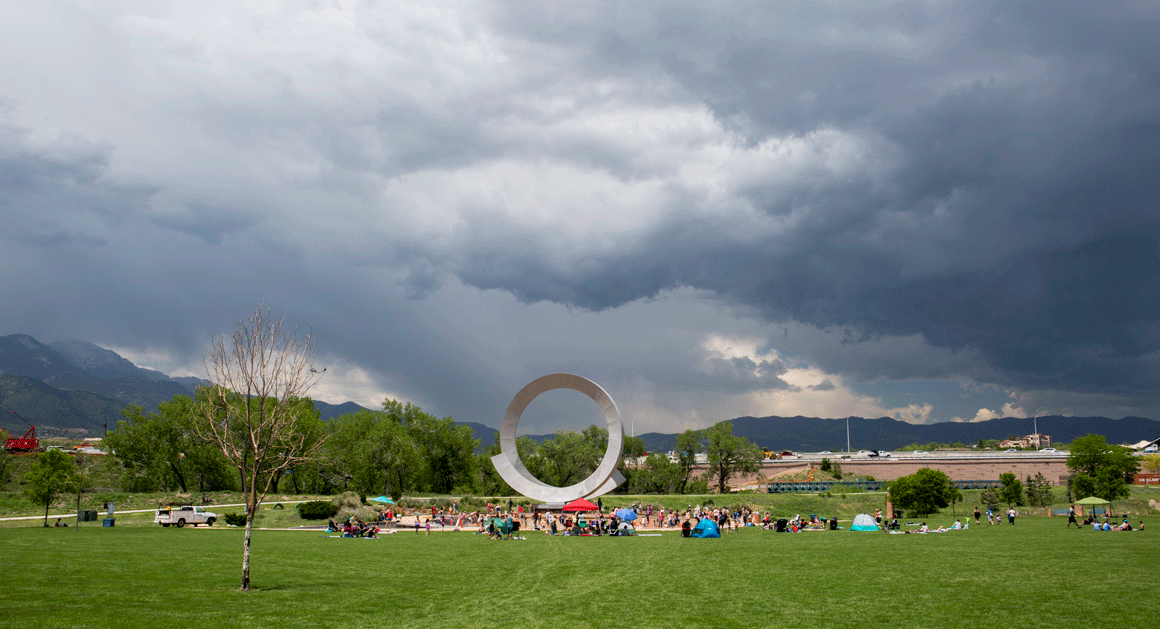

Rocky Mountain Town Colorado Springs has a reputation as a GOP stronghold, though its downtown features art studios, a kombucha shop and a book seller that gives prominent shelf space to Noam Chomsky. | Erika Larsen for Politico Magazine

One of the lessons: There’s a real cost to saving money.

Take the streetlights. Turning them off had saved the city about $1.25 million. What had not made the national news stories was what had happened while those lights were off. Copper thieves, emboldened by the opportunity to work without fear of electrocution, had worked overtime scavenging wire. Some, the City Council learned, had even dressed up as utility workers and pried open the boxes at the base of streetlights in broad daylight. Keeping the lights off might have saved some money in the short term, but the cost to fix what had been stolen ran to some $5 million.

“Sometimes the best-laid plans don’t work out the way you’d hope,” says Merv Bennett, who served on the City Council at the time and asked officials at the utilities about whether the savings were real.

There has been a lot of this kind of reckoning over the past half-decade. From crisis came a desire for disruption. From disruption came, well, too much disruption. And from that came a full-circle return to professional politicians. Including one—a beloved mayor and respected bureaucrat who was short-listed to replace James Comey as FBI director—who is so persuasive he has gotten Colorado Springs residents to do something the outside world assumed they were not capable of: Five years after its moment in the spotlight, revenue is so high that the same voters who refused to keep the lights on have overwhelmingly approved ballot measures allowing the city to not only keep some of its extra tax money, but impose new taxes as well.

In the process, many residents of Colorado Springs, but especially the men and women most committed to making the city thrive, have learned a few other lessons. That perpetual chaos can be exhausting. That the value of the status quo rises with the budget’s bottom line. And that it helps when the people responsible for running the city are actually talking with one another. All it took was a few years running an experiment that everyone involved seems happy is over.

Like many revolutions, the one in Colorado Springs began with a manifesto.

to continue reading, click here.