Politico: “A $60 million pork kickback?”

Unhappy small farmers detect a racket in a pork branding deal—and the USDA signed off on it.

By Danny Vinik

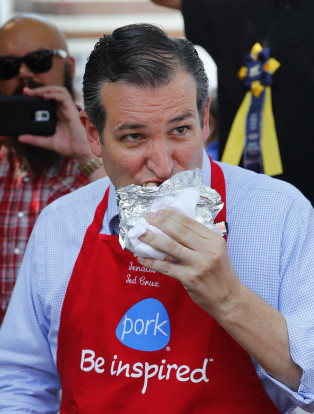

Pork hasn’t been "the other white meat" for years—after a 24-year run as the centerpiece of billboards and the butt of jokes, the slogan was retired in 2011 and replaced with "Pork: Be Inspired," a logo you might have seen on the apron of Ted Cruz as he grilled pork chops at the Iowa State fair last week.

But the National Pork Board, a government-sponsored entity funded by a tax on hog farmers, still writes a check for $3 million every year to license the unused slogan—a bewildering payout that only makes sense, critics say, when you realize the money goes straight to an industrial pork lobby that has long been closely tied to the board. Farmers who pay for the board are crying foul, saying the deal amounts to a scheme to let the board skirt anti-lobbying laws and promote an agenda directly against their interests.

“It’s a shell game,” said Hugh Espey, the executive director of Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, who has been fighting for years to roll back the mandatory payments to the Pork Board.

Saying the U.S. Department of Agriculture should have recognized the deal as corrupt and blocked it, Espey and a group of small hog farmers, along with the Humane Society of the United States, sued the federal government to undo the deal and recoup the millions of dollars already paid for the defunct “other white meat” slogan. Earlier this month a U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit allowed the suit to proceed.

The deal sends $60 million over 20 years from the nonpartisan Pork Board to the slogan’s legal owner, the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC), a lobby with which it once shared an office. Small farmers have long been unhappy about the close relationship between the two groups, and see the rich payments for a defunct slogan as an egregious example of the government taking their money and then letting it be siphoned off to an industry group.

Many critics also see the deal as symptomatic of a far broader problem with the "checkoff" programs that have become common across the agricultural world, in which the government requires farmers to make regular payments to promotional boards. Checkoffs exist for dairy farmers, mushroom producers, and even popcorn processors. Critics say they violate economic freedom and distort the market; big corporate farmers, they allege, easily find ways to influence the boards and siphon the money off to push their own causes.

“In one sense, it’s a classic case of the larger producers are the more powerful political forces within these organizations,” said Dan Glickman, the Agriculture Secretary at the end of the Clinton administration who largely supports checkoff programs.

For the unhappy hog farmers, the current problem started with the 1985 Pork Law, when Congress set up the National Pork Board and required all farmers to contribute. Today, hog farmers must hand over 40 cents out of every $100 in revenue from pork sales. The boarduses the money, totaling nearly $100 million a year, to conduct research and promote the pork industry, but is not allowed to lobby.

The main pork lobby is the National Pork Producers Council, which donated nearly a half million dollars to candidates in the 2014 midterms – mainly, its critics say, to press the interests of big corporate hog farms. Legally, it isn’t supposed to use Pork Board money for its lobbying activities.

But critics say the two groups have never been as separate as the law calls for, and now are essentially colluding through a deal that lets the Pork Board funnel money to the NPCC by assigning an absurdly inflated value to the “other white meat” slogan; the money then goes to promote the NPPC’s lobbying agenda.

The Pork Board referred comments about the case to the USDA. A spokesperson for the department said in an email that “the assessments and expenditures by the National Pork Board were proper,” but declined to discuss the case further.

The NPPC and NPB have always been very close, so close that a 1999 Inspector General report said that the government had to put more space between the two entities to limit the pork lobby’sinfluence at the board.

“It’s a little bit like these super PACs with campaigns. Same people doing the same thing,” Glickman said about problems with the pork checkoff in the late 1990s. “That wasn’t what Congress intended.”

Espey and Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement have long fought the pork checkoff program, and oncecame close to eliminating it altogether. In 2000, opponents gathered enough signatures among hog farmers to force a referendum on the checkoff. More than 30,000 hog farmers voted; by 5 percentage points, they chose to kill the program. Glickman began dismantling it, but the NPPC challenged the referendum in court, and when the Bush administration took officethat January, incoming USDA secretary Ann Veneman reversed Glickman’s decision. Instead, she crafted a “separation agreement” that overturned the referendum result but required the NPPC and NPB to adjust their operations so they were independent.

“It was window dressing. It was bullshit,” Espey said. “Essentially, she was throwing out our vote.”

After the agreement,the NPB and NPPC made some changes.The NPPC could no longer be the NPB’s general contractor, meaning the Board had “to conduct its own programming and coordinate its own activities,” according to the NPB’s own video history. The two groups no longer shared an office and a number of staffers switched from the pork lobby to the board. To the NPB and NPPC, Espey and Co. were simply scapegoating the organizations for their own failures.

The NPPC, which declined comment for this piece, has always owned the “other white meat” slogan, and as part of the separation agreement, itlicensed the slogan to the board for around $1 a year. In 2004, the NPB agreed to increase the annual licensing fee to $818,000 a year. Despite the success of “the other white meat” trademark, an agricultural economist recommended that the board not pay more than $375,000 a year to license the slogan, according to the complaint.

In 2006, the NPB signed a deal to buy the slogan for $3 million a year for 20 years—a four-fold jump in price, even though almost no other group would conceivably have any interest in the slogan.

“Are the artichoke producers competing for the slogan "Pork: The Other White Meat"? No, I don’t think so.” says Parke Wilde, an associate professor of food science and policy at Tufts University who has written extensively about the $60 million deal and considers it corrupt.

According to the plaintiffs, the $60 million valuation came from calculating the cost of creating a new tagline, not on the slogan’s market value. But several specialists contacted for this story suggested that with no other reasonable potential buyers, it’s a mistake to pay the full value.

“If you’re the single buyer out there, you’d expect a deep discount and that deep discount would be at least 25 percent, perhaps 50 percent,” said Weston Anson, the chairman of CONSOR Intellectual Asset Management, a firm that specializes in valuing intellectual property.

Even stranger, to observers, is that when the Pork Board retired the slogan five years later, it continued paying the $3 million to the pork lobby—despite havingthe right to cancel the deal with a year’s notice.

“If they have that out, they should be taking it,” Anson said.

The NPB says that the “other white meat” slogan still has value as a “heritage brand,”though Anson disagreed:“As best as we can determine, they are not using this brand at all. If that’s true, then this is not a heritage brand. Then, it’s a fallow brand—one that’s been retired—and would be difficult to value given that it has no income, no market presence and only residual awareness.”

Though the Pork Board is subject to federal oversight, what worries Espey and others is that it really operates like a private organization entitled to take farmers’ money, and then spend it out of view of the public – all with the blessing of the USDA.

“The real problem with all of these check-offs is they depend on strict USDA oversight in order to achieve their purpose,” Matthew Penzer, a lawyer for the Humane Society, said. “In this case, that oversight has failed.” The Humane Society has long been critical of the pork lobby and the farming techniques of large pork producers.

The suit, filed in 2012, was dismissed for lack of standing in 2013 but the appeals court reversed that dismissal on August 14. The government now has 45 days to appeal the lower court ruling, before thecase returns to the D.C. District Court for a ruling on its substance. In the meantime, the payments continue.