‘Pink Slime’ Makes Comeback as Beef Prices Spike — WSJ

‘Pink Slime’ Makes Comeback as Beef Prices Spike

Surging U.S. Beef Prices Revive Ingredient That Nearly Disappeared Two Years Ago

By

Jacob Bunge and

Kelsey Gee

Updated May 23, 2014 6:58 p.m. ET

Beef Products Inc. makes finely textured beef from scraps sliced away in meat processing. Dave Eggen for The Wall Street Journal

Surging U.S. beef prices are helping to revive a meat product that all but disappeared two years ago.

Finely textured beef, dubbed "pink slime" by critics, is mounting a comeback as retailers seek cheaper trimmings to include in hamburger meat and processors find new products to put it in.

Just in time for the summer barbecue season, the finely textured beef product known as pink slime is making a comeback. WSJ’s Kelsey Gee joins the News Hub with Sara Murray.

Sales of the ingredient—processed from beef scraps left after cattle are butchered—collapsed in 2012 after a social-media frenzy spurred by television reports raising questions about its legitimacy as a beef product. The ingredient’s two largest producers, Beef Products Inc. and Cargill Inc., closed plants that made it and cut hundreds of jobs—while defending the product’s quality and pointing out that the U.S. Department of Agriculture deems it safe.

Today, Cargill sells finely textured beef to about 400 retail, food-service and food-processing customers, more than before the 2012 controversy, though overall they now buy smaller amounts, company officials said. Production of finely textured beef at Beef Products has doubled from its low point.

Earlier Coverage

- Cargill to Label Beef Containing ‘Pink Slime’ 11/05/13

- Beef Products to Shut Plants Over ‘Slime’ Fallout 05/08/12

- Beef Processor Falters Amid ‘Slime’ 04/04/12

- ‘Pink Slime’ Fight Hurts Beef Demand 03/28/12

The resurgence is being driven, in part, by an aversion to something many consumers and companies find even less pleasant than the pink-slime nickname: red-hot prices. Prolonged drought in the southern Great Plains has shrunk U.S. cattle supplies to historic lows. The retail price of ground beef soared 27% in the two years through April to a record $3.808 a pound, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That means serious sticker shock for U.S. consumers preparing to fire up their barbecues for Memorial Day weekend—the traditional start to the summer grilling season. The week leading up to the Monday holiday is typically one of the biggest sales periods for ground beef, with an estimated 160 million pounds likely to be sold during that stretch this year, according to CattleFax, a Colorado-based research firm.

How much of that burger meat contains finely textured beef isn’t clear. Prior to the flurry of media attention in 2012, Beef Products estimates, the ingredient was in as much as 70% of the ground beef sold in the U.S. at retail and in food service. Cargill and Beef Products decline to give a similar estimate now, but they say sales have rebounded sharply from their 2012 lows.

"We’re almost recovered from it," Gregory Page, executive chairman of Cargill, said in a recent interview. Cargill said its sales of finely textured beef have risen about threefold from their lowest point, though overall production remains about 40% below earlier levels.

"Two years ago, no one would return our calls," said Jeremy Jacobsen, spokesman for BPI, which closed three of its four plants in operation in 2012. "Now some of those same people are calling us unsolicited, and we don’t have the sales staff to maintain the new business."

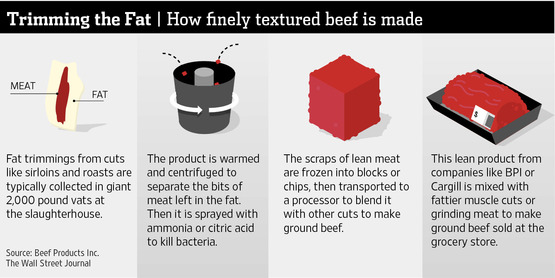

Finely textured beef, produced since the 1990s, is made of pieces sliced away from meat cuts in processing. The scraps generally are 50% fat or more, making them too fatty for most consumers. Meat companies warm the trimmings, separate out the fat in a centrifuge, and treat the remaining lean meat with an ammonia gas or citric acid aimed at killing bacteria like E. coli. The product is shipped to plants that grind it in with other cuts to form hamburger meat.

BPI, whose founder, Eldon Roth, built its business around the product, calls its version "lean, finely textured beef."

Hamburger patties made with lean finely textured beef were prepared in Sioux City, Iowa, in this March 2012 photo. AP

The ingredient began attracting wider attention last decade. A 2009 New York Times article cited a 2002 email by a USDA microbiologist who called the product "pink slime." TV chef Jamie Oliver used the epithet in an on-air critique in 2011. After ABC News reports in 2012 scrutinized the product, a public backlash ensued, spread through social media. That prompted several supermarket chains, including Kroger Co. and Supervalu Inc., SVU +0.54% to drop the beef additive from their meat cases. Neither Kroger nor Supervalu sell the product today.

Critics were partly repulsed by images of the product—some of which the industry says were false—and by the idea of using chemical treatments such as ammonia gas on food products. Supporters of finely textured beef pointed out that many foods contain similar traces of ammonia naturally. BPI says it uses a form of the chemical called ammonium hydroxide. That compound falls under the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s "generally recognized as safe" category, which means they are safe when used as intended.

Officials including Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack defended the product’s safety. But its sales fell so sharply that they effectively reduced total U.S. beef supplies by 2% in 2012, according to agricultural lender Rabobank.

BPI, based in Dakota Dunes, S.D., said it lost contracts with 72 customers, many over the course of one weekend in March 2012, forcing its production to slide below one million pounds a week at their nadir that year. Customers were "dropping like flies," said Mr. Jacobsen, the BPI spokesman.

BPI in 2012 sued ABC and several other defendants for defamation in South Dakota Circuit Court, seeking at least $1.2 billion in damages. The state’s Supreme Court on Thursday affirmed a decision by a lower court to let the case proceed, denying an appeal by ABC. The case hasn’t gone to trial. Jeffrey Schneider, a spokesman for ABC, said the news organization continues to vigorously contest the charges.

At Cargill, about 80% of sales of the product evaporated "overnight" in 2012, said John Keating, president of Cargill Beef. The company ceased production at a plant in Vernon, Calif., in 2012, laying off about 50 workers. Mr. Keating said the lost business also contributed to Cargill’s decision last year to idle a beef-processing plant in Plainview, Texas, where about 2,000 people were laid off. At other plants, production slowed.

Cargill’s meat processors and chefs have been working with its customers to find new uses, such as frozen meatloaf and sausages, though 90% to 95% continues to go into ground beef, Mr. Keating said. Earlier this year Cargill, based in suburban Minneapolis, began to label boxes and packages of ground beef containing the product. Mr. Keating said the labels haven’t much affected Cargill’s ground-beef sales.

"It’s a product we’re working very hard to reintroduce," Mr. Keating said.

Beef Products said it has recovered 40 customers since March 2012, mostly processors and patty-makers who distribute to retailers and the USDA. BPI has added five employees to the sales staff, which now totals 16 people.

Some consumers have no qualms with the product. "I have no health and safety concerns," John Rux, a 69-year-old pharmacist, said while shopping this week at a Mariano’s grocery store in Chicago. Still, "they should probably be forced to" label it, said Mr. Rux, who sometimes prefers to buy beef he believes contains the ingredient because he thinks it is cheaper, among other reasons.

Hy-Vee Inc., a 235-store grocery chain based in West Des Moines, Iowa, dropped ground beef containing the ingredient amid the March 2012 uproar, but reversed course later that month, citing customer requests. Packages it sells that contain finely textured beef are so labeled, a spokeswoman said. Customers "are buying it just as they were before the whole issue blew up," she said.

Still, problems remain. A further drop in U.S. cattle supplies projected for later this year "will put a lid on the amount of product Cargill and BPI can produce," said Steve Kay, publisher of Cattle Buyers Weekly, an industry newsletter.

And some consumers still find the beef additive unappetizing. "The whole pink-slime episode really did affect my thoughts on ground beef," said Tina Engberg of Marietta, Ga. The 46-year-old said her two children love hamburgers, but she buys less of it than she used to. "Ground beef should be as simple as what I did last week when I was grinding a chuck roast and cooking it up."

—Julie Jargon contributed to this article.

Write to Jacob Bunge at jacob.bunge and Kelsey Gee at kelsey.gee