Omaha World-Herald: Grace: Gov. Ricketts’ book snub creates a run on ‘This Blessed Earth’

by Erin Grace / World-Herald staff writer | January 14, 2019

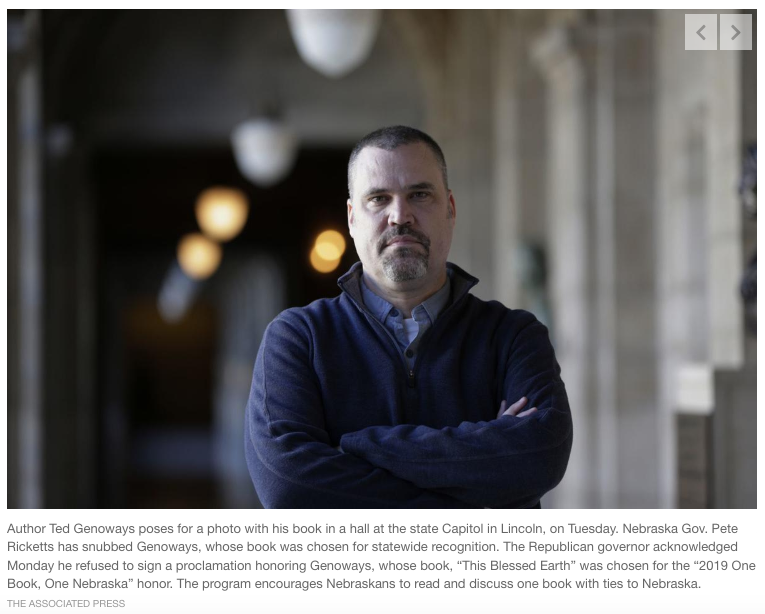

At the end of his unintentionally controversial book about a Nebraska farm family, Ted Genoways thanks his supporters.

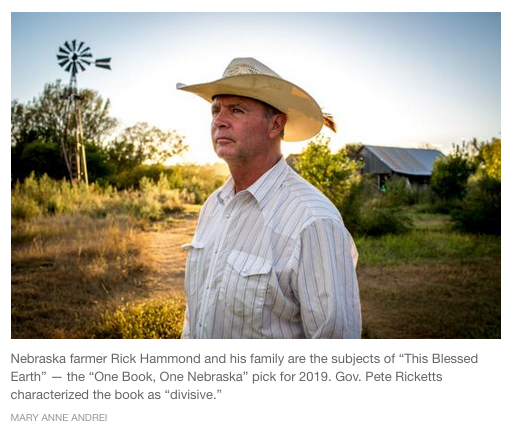

Following a long tradition, the author of “This Blessed Earth” thanks his wife, photojournalist Mary Anne Andrei, for the idea to chronicle the ups and downs of a Nebraska farm family.

Genoways thanks the Hammond family for allowing interlopers into their lives for a full year, beginning with the fall harvest in 2014, at their east-central Nebraska farm .

He thanks his editors at W.W. Norton & Co., the New York-based publishing house that saw this as a compelling story about American agriculture and published it in 2017.

But Genoways might need to add to his acknowledgments one more name: Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts. For in refusing to promote a book, our governor wound up promoting it. That’s how it goes with forbidden fruit.

After Monday’s dust-up in which Ricketts backed out of a public proclamation and ceremony for the “One Book One Nebraska” selection for 2019, sales went through the roof. (The award-winning book is Iowa’s selection, too.)

Amazon sold out. Local bookstores in Omaha and Lincoln sold out. The Omaha Public Library, as of Friday, had almost 90 holds on its print and audio copies of “This Blessed Earth.”

Beth Black, owner of The Bookworm in Omaha, said the store has a waiting list with more than two dozen names on it, including buyers who want multiple copies. She said that even the regional distributor is out of copies and that the Norton sales rep asked if she could have Ricketts publicly refuse to read other Norton books.

“‘This is working out very well for us,’” Black said her sales rep told her. “It’s Parenting 101, right? You tell your kids not to do something. What are they going to do?”

In the long tradition of book dissers, Ricketts said Monday that he hadn’t read the 240-page book. While he didn’t tell anyone NOT to read the book, he characterized it as “divisive,” the work of an activist out of touch with regular Nebraskans.

In fact, Genoways has deep Nebraska roots and lives in Lincoln. His other bona fides include:

Academic. Genoways holds a doctorate in English, authored two books of poetry and a biography on Walt Whitman, and edited the Virginia Quarterly Review, the literary publication of the University of Virginia.

Journalistic. Genoways is a contributing editor at Mother Jones, The New Republic and Pacific Standard. He has won numerous writing honors and awards.

Give Genoways credit for writing compellingly about seemingly dry subjects like soybeans and irrigation, weaving in history lessons on the Homestead Act, the Civil War and technological invention.

I beat the rush to the library and finished “This Blessed Earth” in two days. First takeaway: Why would anyone on this blessed earth try to farm? Farming sounds so hard and so complex and requires so much: MacGuyver-like mechanical ability, hedge fund manager market smarts, steel nerves for constant gambling on weather and markets, and emotional strength to gut out painful family succession. Plus, no shortage of luck.

Because we live in a partisan time when we tend to view the world through blue- or red-tinted glasses, I could see why Ricketts might balk at first glance.

The book’s protagonists, the Hammonds, are Democrats who are fiercely against the Keystone XL pipeline. Ricketts is a pro-pipeline Republican. The book also offers a peek behind the curtain of how big ag and big government affect the man or woman driving the combine. This might make a pro-business governor uncomfortable.

But that’s all wallpaper for a bigger story about what the Hammond family is up against: Fickle weather. Fickle markets. Murphy’s Law.

Plant too close to the center pivot and, during harvest, the driver might misjudge the turn and whack the harvester against the irrigator. Lug a 150-pound replacement gearbox through a field to replace the busted one, and it will turn out to be the wrong gearbox. Do everything right and then get rain and hail. Because most of us don’t have any real idea of what’s involved with farming outside of “Charlotte’s Web,” this book will be a real eye-opener.

Genoways presents a very Steinbeckian story: Americans struggling heroically against forces outside their control. Genoways presents the Hammonds as real people, not rural caricatures.

Rick Hammond is a plucky risk taker who nevertheless second-guesses his decisions. His public protest of the Keystone XL pipeline cost him dearly when a neighbor got mad and pulled out of a longstanding agreement over rented farmland.

Daughter Meghan is both strong and sensitive to criticisms lobbed by those who want organic and antibiotic-free food but don’t have a clue about how hard it can be to earn that distinction. Does a farmer NOT treat cattle when pinkeye is running through the herd?

You see how she grapples with rebuilding her life after her high school boyfriend was killed on tour in Iraq. And her new boyfriend-turned-husband Kyle Galloway is so hardworking and mechanically gifted that he’s easy to root for, but your heart sinks when he makes an honest mistake.

How true was this depiction of a Nebraska farmer’s life?

“You could replace ‘Hammond’ with ‘Rasmussen’ very easily, and it’s my family,” said Jordan Rasmussen, whose husband is a sixth-generation farmer in Saunders County. “This is our story.”

Rasmussen, like many farmers, has a day job. Hers is working in policy for the nonprofit, nonpartisan Center for Rural Affairs in Lyons, Nebraska. She said that she hears from farmers driven to the brink by property taxes, market fluctuations and tricky succession timelines and that she read the book soon after it came out in 2017. In it, she could see herself.

“I’m not out every day feeding cattle and driving the combine. But I’ve built fence. I’ve helped replace irrigation pivot sprinklers. I’ve come home and seen my husband banged up and bruised,” said Rasmussen. “I would say yes, (the book) is very much a reflection, and I very much identified with the challenges the Hammonds were talking about.”

Chris Clayton, an Iowabased journalist for the ag publication DTN — The Progressive Farmer — and a former World-Herald reporter, said the book was so true to life that he wished that he had written it.

Genoways, who wrote about the Keystone XL issue as a reporter, is not some outsider who parachuted in with a political agenda and a lack of appreciation for who farmers are and what they do, something he saw in some of the coastal journalists and environmentalists who came to Nebraska and the Dakotas.

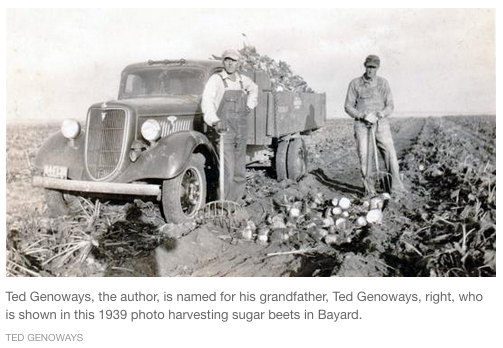

His roots run deep in western Nebraska. His father is from Bayard. His mother is from Scottsbluff. A great-grandfather, L.C. Genoways, was the Hamilton County assessor. A grandfather, Ted, was a ditch rider, an unattractive-sounding title for someone whose irrigation-ditch monitoring job was vital to the farm economy. His father, Hugh, was museum director of Morrill Hall and director of museum studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Ted Genoways spent his formative years growing up in Pittsburgh and visiting Nebraska relatives, fascinated about their rural life. When his dad got the UNL job, the family moved to Lincoln. He graduated from Lincoln East and Nebraska Wesleyan.

After moving for his doctorate (University of Iowa) and jobs, he and wife Mary Anne, now emerging media producer for NET, resettled in Nebraska in 2012 and now live in Lincoln. They have a 16-year-old son who attends Lincoln High.

Genoways spent some of last week on Twitter poking at Ricketts and noting his campaign donations to Republican hardliner Rep. Steve King of Iowa. He said he doesn’t see himself as an activist or as an outsider. Nor did he set out to do anything divisive in writing a book that he hopes gives voice to people who are relatively invisible to the rest of us and have to live with the rules established by politicians and corporations.

“To the extent that I have an activist streak,” he said, “that streak is that I want to hear from people who aren’t heard.”

Thanks to Ricketts’ un-blessing of “This Blessed Earth,” readers across Nebraska appear to be listening. Eagerly.