NOBULL: Why Big Meat hates ‘Made in the USA’ labels

Why Big Meat hates ‘Made in the USA’ labels

· BY LYDIA DEPILLIS

·

· May 1 at 5:08 pm

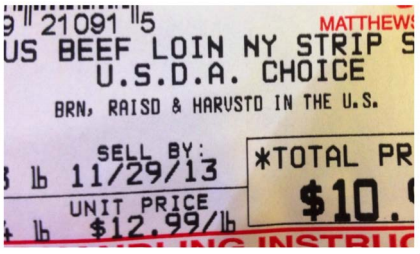

What labels look like now. (National Farmers Union)

Conventional marketing wisdom is pretty clear on "Made in the USA" labels: If you canactually prove your product is made and assembled domestically, trumpeting the factcan’t hurt. That’s true, at least, of things like apparel, phones, and kids’ toys. Turns out it’s not really true about meat.

For many products, country-of-origin labeling has been a requirement for a long time. But it was only mandated for food in the 2008 Farm Bill, which decreed that most meat and produce carry a sticker with the place it came from (or, at least, where it was born, raised, and slaughtered). At the time, the benefits were thought to outweigh the costs: Consumers said they wanted to know the source of their staples, and even indicated they might pay more for U.S. products if they thought they were safer.

But after a few years of that, it appears consumers barely notice the labels, and American meats aren’t commanding a premium because of them. A 2012 study from Kansas State University found that buyers didn’t realize whether something was produced in America or produced in North America, and there was no change in demand either way.

At the same time, however, Canada and Mexico do think the labels were having an impact — or at least might start having one eventually — and sued the United States over the new mandate at the World Trade Organization. They won, and the U.S. was ordered to revise its statute so that it doesn’t discriminate against foreign producers, or at least so that the labels provide enough information to justify their effect. If U.S. regulators don’t manage to do so to the satisfaction of our neighbors to the north and south, they could slap similar sanctions on U.S. products, which could pose a problem for American protein providers that depend heavily on exports.

So in May of last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued a new rule, which makes the labeling requirements more substantive by requiring meat producers to separate U.S.-born from foreign-born livestock at every step of the process — no commingling allowed.

And this is where we learn something about how the sector works: As with so many products in the globalized, integrated economy, there is no "American" meat industry. Most of the large scale meatpackers, like Tyson Foods, buy animals from both Canada and Mexico and bring them to U.S. slaughterhouses, which are all subject to the same safety standards. As several meatpacking trade associations led by the American Meat Institute put it in their lawsuit against the new rules: "In short, beef is beef, whether the cattle were born in Montana, Manitoba, or Mazatlán. The same goes for hogs, chickens, and other livestock." (The lawsuit, which will get a full hearing before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, alleges that the labeling requirements are a form of "compelled speech" that violate meatpackers’ first amendment rights.)

There are, however, some meat-producing interests that still favor the country-of-origin labels: American ranchers themselves, who just provide the animals, and don’t have to deal with separating streams of livestock from all over the continent and tracking it to its destination. (In D.C. advocacy world, this can get confusing: TheNational Cattlemen’s Beef Association opposes the labeling requirements, but the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association supports them.) These are the people who are worried about mega-corporations taking over agricultural production, and also worry about the impact of free trade deals that have allowed in more imports than they’ve boosted exports.

Foremost among them is the National Farmers Union, which testified strongly in favor of the labeling requirements at a congressional hearing on the state of the livestock industry Wednesday, and also offered this chart of how quickly the industry has consolidated:

In a somewhat unlikely demonstration of the power of smaller producers over massive agribusiness interests, the National Farmers Union, U.S. Cattlemen’s Association and their allies have played the political game fairly effectively, and now the meatpackers have hung their hopes on the outcome of their lawsuit as well as Canada and Mexico’s cases before the WTO to make the labels go away. But if you buy their argument, you probably didn’t notice the labels anyway.

Lydia DePillis is a reporter focusing on business policy, including lobbying, government contracting, and international trade, with a bit of urban affairs and infrastructure on the side. She was previously a staff writer at The New Republic and the Washington City Paper. Email her here and follow her on Twitter here.

Well since beef is beef, my Ford Pinto is just the same as the next guy’s Ferrari Spider!