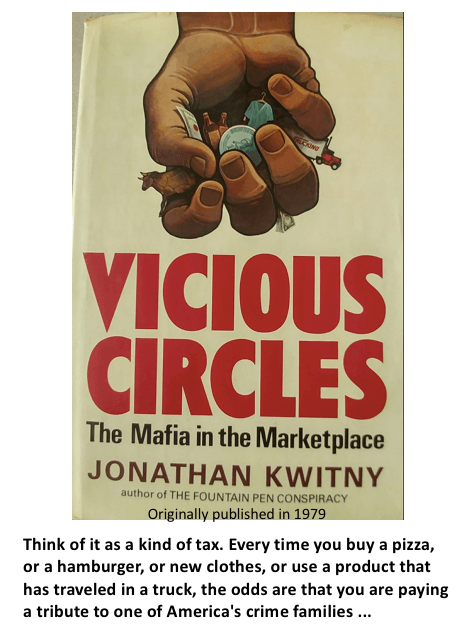

No-Bull Food News: Vicious Circles – Big meat packers continue to suck the blood out of cattle industry

by Mike Callicrate | May 24, 2018

For no reason whatsoever, other than they can, the big meat packers took another $130 per head off the value of live cattle last week, leaving a decaying carcass of what’s left of the cattle industry.

Few people know the history of meat packing in the U.S. and the reason the ruthless meatpacker monopoly as broken up in the 1920’s, only to return bigger and even more powerful today.

An excerpt of the story of how IBP (now Tyson/IBP) fell under the control of the New York Mafia follows. Today, not much has changed. The top executives of Brazil’s JBS, the world’s biggest meat packer, are either in jail or out wearing ankle bracelets, after bribing 2,000 politicians and meat inspectors. Also, Brazil’s Marfrig, the world’s second biggest meat packer, just purchased fourth largest U.S. beef packer, National Beef. Marfrig’s chairman has offered to cover $22.98 million in damages in a recent corruption probe.

On opening day of trial in 2004, I called Tyson/IBP gangsters, thugs and thieves. Tyson didn’t like it and threatened to sue me if I didn’t retract the statement. Here’s my response to the Tyson lawyers.

Much more is revealed in Christopher Leonard’s book, The Meat Racket.

Do we want a no-rules food system in which the biggest cheaters win, and monopolies control our food supply? It’s what we have today.

On April 25, 1970, a scruffy, half-literate little manipulator named Moe Steinman shuffled into a suite at the elegant Stanhope Hotel overlooking Central Park in Manhattan, pulled the blinds, and within a few hours assumed a stature that even the most celebrated racketeers in history hadn’t dreamed of.

Other mobsters had gone only partway. Gurrah Shapiro had controlled the garment center, and Joe Bonanno the Brooklyn dairy products district. Steinman had also gone partway – he had dominated the Fourteenth Street meat market. Some racketeers before Steinman had persuaded the heads of rival Mafia families to unite behind a single organized shakedown system. Thus had Steinman united racketeers from three powerful Mafia families, Genovese, Gambino, and Lucchese, and become the meat industry front for all of them. Other racketeers, before Steinman, had achieved nationwide control over certain specialty products, like mozzarella cheese, or over an atomized industry, like trucking.

But on this day, Moe Steinman, as a front for the Mafia, would achieve what no one else had achieved, even in the days of Al Capone or Lucky Luciano. Moe Steinman, who had risen from the gutter only by his lack of scruples, would tighten his fist around one of the biggest corporations in the country, a corporation that dominated a major national industry. It was an industry that almost every American depended on almost every day. It was an industry – unlike trucking – that was clothed with all the garments of Wall Street respectability.

Into this darkened room at the Stanhope Hotel, Moe Steinman would summon Currier J. Holman, founder and head of Iowa Beef Processors Inc., by far the largest meat company in the world. Then, as now, Iowa Beef’s name was listed in the upper levels of the Fortune 500 ranking of largest corporations. Its shares were traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Its financing was handled by a syndicate of the biggest banks in the country. Then, as now, its sales were in the billions of dollars, and its food was on the tables of millions of Americans from Bangor to San Diego.

And Currier J. Holman, the tall, graying Notre Dame alumnus and widely-recognized business genius who organized and ran this mammoth operation, was to come crawling all the way from the Great Plains, bringing with him his co-chairman, his executive vice-president, and his general counsel, all at the beck of a foul-mouthed alcoholic hoodlum.

“Iowa Beef, though founded only in 1961, already in 1970 dominated the meat industry the way few other industries are dominated by anyone.”

Iowa Beef, though founded only in 1961, already in 1970 dominated the meat industry the way few other industries are dominated by anyone. Since then, in partnership with Steinman and his family and friends, Iowa Beef has grown more dominant still. It was as if the Mafia had moved into the automobile industry by summoning the executive committee of General Motors, or the computer industry by summoning the heads of IBM, or the oil industry by bringing Exxon to its knees. Moe Steinman and the band of murderers and thugs he represented had effectively kidnapped a giant business. Its leaders were coming to pay him the ransom, a ransom that turned out to be both enormous and enduring.

“Moe Steinman and the band of murderers and thugs he represented had effectively kidnapped a giant business [IBP].”

As a result of the meeting in the darkened suite at the Stanhope that day in 1970, Iowa Beef would send millions of dollars to Steinman and his family under an arrangement that continued at least until 1978. After the meeting, millions more would go to a lifelong pal of Steinman and his Mafia friends, a man who had gone to prison for using slimy, diseased meat in filling millions of dollars in orders (he bribed the meat inspectors) and who wound up on Iowa Beef’s board of directors. Consequent to the meeting in the Stanhope Hotel, Iowa Beef would reorganize its entire marketing apparatus to allow Steinman’s organization complete control over the company’s largest market, and influence over its operations coast-to-coast. In 1975, Iowa Beef would bring Moe Steinman’s son-in-law and protege to its headquarters near Sioux City to run the company’s largest division and throw his voice into vital corporate decisions. But, most important, a mood would be struck in the Stanhope that day – a mood of callous disregard for decency and the law. Iowa Beef would proceed to sell its butcher employees out to the Teamsters union, to turn its trucking operations over to Mafia-connected manipulators, and to play fast and loose with anti-trust laws.

“a man who had gone to prison for using slimy, diseased meat in filling millions of dollars in orders (he bribed the meat inspectors) and who wound up on Iowa Beef’s board of directors.”

Because of their hold on Iowa Beef, the racketeers’ control of other segments of the meat industry would expand and harden. And as a result of all this, the price of meat for the American consumer – the very thing Currier Holman had done so much to reduce – would rise. Meyer Lansky once said that the Syndicate was bigger than U.S. Steel. When Iowa Beef Processors caved in on that April day in 1970, the Syndicate, as far as the meat industry was concerned, became U.S. Steel.

“Because of their hold on Iowa Beef, the racketeers’ control of other segments of the meat industry would expand and harden.”

Moe Steinman is not impressive to look at. He is of average height, but seems shorter. He isn’t fat, but there’s something overweight about him. He has a sad, doberman-like face, that is pockmarked and ruddy like a drunk’s. Steinman is often drunk. His clothes are sometimes flashy, but seldom tasteful. He is appallingly inarticulate when he talks. But everybody knows what he means.

Detective Bob Nicholson once stood near the bar of the Black Angus restaurant and saw a slightly tipsy Moe Steinman point his stubby finger at John “Johnny Dio” Dioguardi, the foremost active labor racketeer in the Lucchese Mafia family. “You listen here, Johnny,” Steinman said. “You don’t tell me how to run my business. I tell you.” The boast rocked Nicholson (and Dio may not have cared for it, either). Ultimately, the Mafia retained its power, through its violent system of justice. But the fact that Steinman was allowed to get away with such bragadoccio – and he did it repeatedly – showed just how indispensable he had become to the Mafia’s design on controlling the marketplace. There is a story in the industry that once in the late 1960s Steinman brazenly cheated Peter Castellana, a relative and high aide of boss Carlo Gambino. Steinman is said to have short changed Castellana on the sale of a load of hijacked turkeys. And nobody raised a finger.

Industry sources also talk about a speech Steinman gave in 1970 at a retirement party for a Grand Union supermarket executive. The party, naturally enough, was at the Black Angus, which was owned by a retired executive from the rival Bohack chain, who had acquired it from the family of the retired head of the butchers’ union. While the departing Grand Union official was guest of honor at the party, the center of attention was Johnny Dio, who also was about to depart, in his case for prison, where he was being sent as a result of illegal deals in the kosher meat industry. Steinman, it’s said, stood up before the assembled guests, openly recalled how close he was to Dio, and assured everyone that he personally would “take care of business” while Dio was away.

Only once, in the mid-1960s, is Steinman said to have suffered Mob disfavor. There are reliable reports that he was beaten up once in a supermarket warehouse, and hospitalized. Nobody who is willing to talk seems to know for sure what the beating was about.

Bob Nicholson had been impressed the first time he heard Steinman’s name, back in 1964 in the Merkel horsemeat scandal. When Merkel’s boss, Nat Lokietz, wanted a connection in government so he could bribe his way out of trouble, he had called Moe Steinman. Steinman didn’t arrange the bribe meeting – Tino De Angelis did – because Steinman was out of town. But after the bribery attempt backfired, Lokietz went to Steinman again ina last-ditch effort to keep Merkel afloat. In the spring of 1965, Steinman had met with Lokietz at the Long Island home of a Big Apple supermarket meat buyer, who acted as intermediary. The buyer was in Steinman’s pocket; he would later plead guilty to evading income taxes on payoffs he took from Steinman. Through subsequent conversations that were wiretapped, police learned that Lokeitz had asked Steinman to get the Mafia to rescue Merkel. Some money, some political clout, and Lokietz could be back on his feet again. Steinman huddled with Dio over the idea one night at the Red Coach Inn in Westchester County, but with the horsemeat scandal all over the papers and Dio involved in some promising new rackets, they decided to let Merkel go on down the drain.

As a result of these meetings, however, Steinman was called in for questioning before the Merkel grand jury. Nicholson was sent to serve the subpoena, and thus got to meet the racketeer for the first time. Immediately Nicholson saw the arrogant conniver that was Steinman, a man who thought he could wheel and deal his way out of anything.

Nicholson found Steinman at the Luxor Baths, the famous old establishment on West Forty-sixth Street where the wealthiest of New York’s European immigrant community used to go. There they relived the old-country male ritual of a steam bath, a massage, and a nap. Numerous business and entertainment celebrities had visited the Luxor over the decades. But by the late 1950s, the clientele had cheapened a bit and mobsters were more in evidence. The bathhouse was a frequent hangout for the likes of Johnny Dio, Anthony “Tony Bender” Strollo, and Lorenzo “Chappy the Dude” Brescia. Wiretaps would later reveal that the Luxor served as a convenient location for underworld plotting and the passing of payoffs. It was at the Luxor that Steinman often took care of supermarket executives and butchers’ union officials. In 1975, the Luxor Baths closed, and reopened as a house of prostitution.

Nicholson remembers going into the lobby of the Luxor with his subpoena in 1965, and paging Steinman. The stocky (but not fat) racketeer came down in his bathrobe and turned on his crude charm.

“Can you tell me what this is about?” he asked Nicholson.

“Sorry,” he was told. “I can’t discuss it.”

“Why don’t we sit down to talk?”

Nicholson looked around at the well-appointed lobby, and then at Steinman in his bathrobe.

“Come on into the steam room. We’ll have a nice bath,” Steinman said.

Nicholson turned him down, but kept him talking. Maybe there would be an open offer of a bribe.

“After we have a bath,” Steinman said, “we can talk. We’ll have a few drinks, maybe we can go out to dinner.”

Nicholson kept him talking.

“Are you married?” Steinman went on.

Nicholson said he wasn’t.

“Do you have a girlfriend? May I could get you a girlfriend. I’m a nice guy. You’ll like me.”

“I had to say, ‘No thanks,'” Nicholson recalls now. “Anything further would have been a compromise. But that’s the way Moe Steinman operates. He never gets caught.”

Others have noticed the same phenomenon. Says a partner in a large and long-established New York meat supply company, “Steinman bribes people in the bank not to sign him in or out when he goes to his safety deposit boxes. He has boxes all over the city. Once I was with him on a trip overseas and he bribed the guy at the airline counter $20 to avoid a $50 overweight charge. He didn’t need the money. It’s just a game with him.”

Steinman was wrong when he thought he could bribe Bob Nicholson. But there were ways over Nicholson and around Nicholson. Even when the law had Steidman absolutely dead to rights in 1975, he was able to manipulate his way out of trouble. Bob Nicholson was right about one thing: “He never gets caught.”

Moe Steinman has declined numerous requests for an interview. His communications to the author have consisted mostly of grunted greetings and monosyllabic comments in the hallways of various courthouses. There was also a very pregnant stare on day in a visitors’ room at the federal Metropolitan Correctional Center in Manhattan when Steinman showed up at what I had been told would be a secret meeting between me and a cellmate of his.

Much of Steinman’s story, however, can be told from the public record. He has testified several times about his background (while his veracity has not been constant, certain facts can be verified). And many persons in the meat industry, including his son-in-law Walter Bodenstein, have contributed information to the following sketch.

Steinman was born in Poland around 1918. He came to the United States with his parents at age eight. His father, a butcher, settled in Brooklyn. He quit school after eighth grade and ran off to be a porter or cary worker at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. He returned to Brooklyn, where a young greengrocer named Ira Waldbaum had decided to lease out sections of his stores to meat dealers. This was, of course, long before Waldbaum’s became the major regional supermarket chain it is today.

A dealer who had leased the meat departments in two Waldbaum’s stores hired young Moe Steinman to run them, and the budding hoodlum was on his way. Steinman bought his first meat from Sam Goldberger, who would later go to prison for selling adulterated meat and bribing federal food inspectors. And Steinman made connections with two other Polish-Jewish immigrants, Max and Louis Block, who had just left their own Brooklyn butcher business to organize the Amalgamated Meat Cutters’ union under rights obtained through mobsters Little Augie Pisano and George Scalise. Pisano and Scalise were of an older generation, but there was a younger, more contemporary Mafia figure whom the Blocks and Steinman and Goldberger began to meet – Johnny Dio.

Soon Steinman was expanding his meat counter operations to the Bronx …