Newsweek: Dollar Stores Planning for Permanent American Underclass, Sell More Groceries Than Whole Foods

by Andrew Whalen | December 7, 2018

Dollar-store chains like Dollar General and Dollar Tree are rapidly expanding by targeting the poor, particularly in predominantly black neighborhoods and rural areas, while planning for a permanent American underclass, according to a new report from the community development nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR).

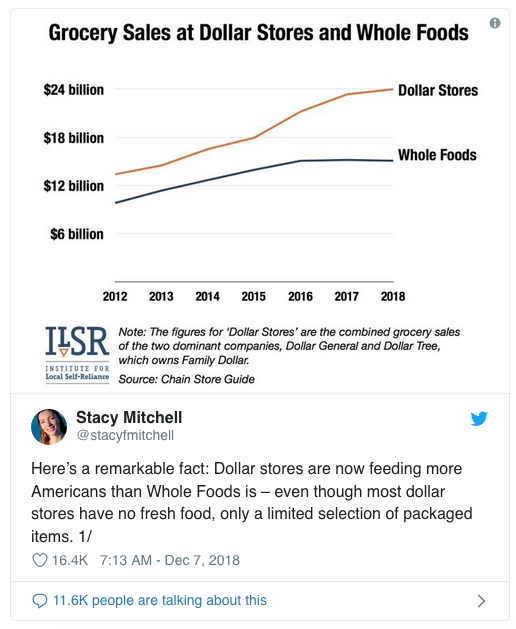

Though dollar stores sell no fresh vegetables, fruits or meat (Dollar General is testing produce in fewer than 1 percent of its stores), they are quickly becoming one of the primary ways lower-income Americans eat, with the combined grocery sales of Dollar General and Dollar Tree outstripping Whole Foods by more than $10 billion.

Selection is limited to processed or canned foods such as cereals, microwaveable meals and snacks. A section on the Dollar General website for “Fresh Food” advertises Banquet Mega Bowls fried chicken, frozen pizzas, Lunchables, Hot Pockets, blocks of cream cheese and pumpkins.

There are nearly 30,000 dollar stores nationwide, more than Starbucks and Walmart combined, and up from 20,000 in 2011. Dollar General and Dollar Tree are planning 20,000 more. Dollar General is opening four stores a day, a rate the company is expected to maintain through 2019.

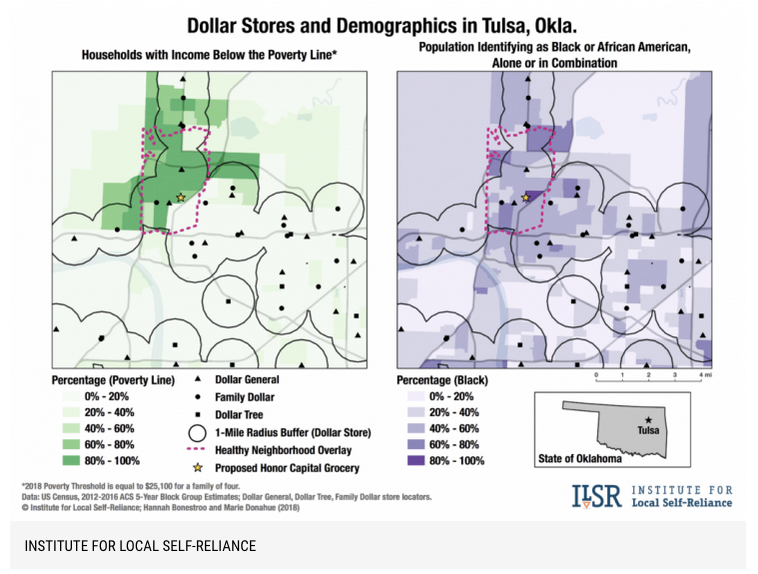

Their customers are made up of three demographics: poor people, black people and rural people. The ILSR documented, with Tulsa, Oklahoma, as its test case, how the presence of dollar store chains can correlate even more strongly with race than income, with locations opening in food deserts historically neglected by supermarket chains.

“Essentially what the dollar stores are betting on in a large way is that we are going to have a permanent underclass in America,” real estate analyst Garrick Brown told Bloomberg in 2017.

Dollar General CEO Todd Vasos agreed, telling The Wall Street Journal, “The economy is continuing to create more of our core customers.” In other words, the more lower-income Americans struggle, the better dollar stores do.

The market tends to agree as well, with Dollar General Corp. valued far above the largest grocery chain, Kroger Co., which still has revenue five times that of its dollar-store competitor. One reason is the dollar-store profit margin, which is significantly higher than grocery stores thanks in part to small-quantity packaging designed to keep prices low even as the value drops, providing customers less for their money.

That isn’t a result of consumer irrationality, but rather is a necessity for lower-income households, whose pinched budgets don’t allow for bulk purchases. Dollar General store manager Damon Ridley spoke to the Journal about helping older children put together enough food for younger siblings with scarce dollars. “I am more of an outreach manager,” he said.

Of course, Dollar General isn’t the only company riding these trends. In 2017, Coca-Cola created a Dollar General exclusive: soda cans with military-aimed labels like “Service Member” and “Military Spouse”—an innovative response to the 1.5 million veterans living in poverty.

More than a harbinger of how corporations will profit from a permanently stratified United States (and work to perpetuate that stratification: Dollar General joined other retailers in lobbying for the Republican attempt to fully repeal Obamacare earlier this year), dollar stores are both symptom and disease.

The ILSR, which authored the report, was founded in 1974 to find localized solutions to environmental and economic problems, and promotes community banking, municipal broadband, composting and localized solar power programs. Its research into Dollar General focused on localized harm and possible community responses, documenting how the opening of a dollar store can cause local grocers to lose up to 30 percent of sales, resulting in declining employment and reduced food access.

“I don’t think it’s an accident they proliferate in low socioeconomic and African-American communities,” Tulsa City Council member Vanessa Hall-Harper told the ILSR. “That proliferation makes it more difficult for the full-service, healthy stores to set up shop and operate successfully.”

In April 2017, Hall-Harper pushed through the first measure in the country to target dollar stores by limiting the number of locations allowed in Tulsa’s historically black north side—which does not have a single full-service grocery store—and incentivizing access to fresh food by offering zoning perks to grocery stores.

“The parallel between these rural towns and urban neighborhoods like North Tulsa suggests that America’s real divide is not so much rural versus urban. Rather, it’s between the few large and mostly coastal cities that are prospering in an economy increasingly dominated by a few corporate giants and the many other cities and regions that are being left behind,” the ILSR concluded.