New York Times: Who Wants to Run That Mom-and-Pop Market? Almost No One

Felix Romero at the R&R Market in San Luis, Colo. The market is the oldest business in Colorado, built by descendants of Spanish conquistadors.

Nick Cote for The New York Times

By JULIE TURKEWITZ | July 26, 2017

SAN LUIS, Colo. — Each morning as the sun curves over Main Street in this isolated desert town, Felix Romero takes the worn wooden steps from his upstairs apartment to his downstairs grocery.

He flips open the lock on a scratched blue door, turns on the lights and begins to sweep, just as his family has done since 1857.

But R&R Market — the oldest business in Colorado, built by descendants of Spanish conquistadors in the oldest town in the state — is in danger, at the edge of closing just as rural groceries from Maine to California face similar threats to their existence.

“If that little store closes, it’s going to be catastrophic,” said Bob Rael, director of the economic development council in Costilla County, where San Luis is the seat. “Reality is going to set in. Who let this happen?”

Across the country, mom-and-pop markets are among the most endangered of small-town businesses, with competition from corporations and the hurdles of timeworn infrastructure pricing owners out. In Minnesota, 14 percent of nonmetropolitan groceries have closed since 2000. In Kansas, more than 20 percent of rural markets have disappeared in the past decade. Iowa lost half of its groceries between 1995 and 2005.

The phenomenon is a “crisis” that is turning America’s breadbaskets into food deserts, said David E. Procter, a Kansas State University professor whose work has focused on rural food access, erasing a bedrock of local economies just as rural communities face a host of other problems.

In New York or Los Angeles, the loss of a favorite establishment is an event to be mourned. But in this ranch town, where the closest reliably stocked market is 40 miles away, the threat to R&R Market raises questions about the community’s very survival.

Mr. Romero and his wife, Claudia, have worked in this shop seven days a week for 48 years, doling out bread and tamal flour, diapers and fishing rods, medicines and ranch tools. Now, they have reached their 70s and are trying desperately to sell.

The problem is finding a buyer at a time when owning the local grocery is a high-risk endeavor, and when President Trump’s budget proposal for 2018 calls for billions of dollars in cuts to aid for rural America, including programs like food stamps and business loans that help small groceries.

The White House has said the plan is intended to reduce the debt burden for future generations. But it has Republicans and Democrats alike expressing fear for rural districts.

To visit San Luis is to enter a world that has persisted despite, or perhaps because of, the most extreme of circumstances.

Six hundred forty-five people live in this village just north of the New Mexico border. Most bear the names of the Mexican settlers who came here in the tense days of the Wild West: Gallegos. Mondragon. Romero.

In town, residents still speak the Spanish of their ancestors. And on the outskirts, fields of alfalfa sip from an irrigation ditch that those settlers dug by hand.

This is high desert country, where a few inches of rain fall in a year, winters dip far below zero and the big city nearby is Alamosa, population 9,918. There is no bank, no gas line, and the electricity sometimes goes out for hours.

The market was built in 1857 by José Dario Gallegos, a merchant and Mr. Romero’s great-great-grandfather, who turned his store into a hub. His descendants have operated it since, filling the shelves with vegetables, locally grown bolita beans and hand-packed chiles.

With few jobs available beyond farming and the two new marijuana shops on Main Street, a third of the town and two-thirds of the children live in poverty.

Food stamps are common currency. Thirty percent of the county receives them.

Mr. Romero and his wife offer food on credit, supply baptisms and funerals, cash checks, issue hunting licenses, pay local taxes. But they are exhausted. And yearning to retire.

“Claudia and I have given up our lives for this,” Mr. Romero, 71, said. He adjusted his now-gray ponytail and pulled out the pages of a novel he wants to finish writing.

“I don’t want to be the one to break tradition,” he said. “But I can’t be here the rest of my life, either.”

Felix and Claudia Romero, the owners, in their apartment above the market.

Nick Cote for The New York Times

Small markets across the country face similar challenges. Many of the men and women behind the cash registers have reached retirement age, and few people want to take over. Profit margins at independent groceries are slim, typically 1 to 2 percent, and last year a quarter of the independent markets surveyed by the National Grocers Association experienced losses.

Customer bases are declining. The cost of upkeep can be overwhelming. Slow internet means inventory orders can take all day. Old refrigerators suck up electricity and money.

Because San Luis has no natural gas line, residents use propane tanks or wood stoves, and Mr. Romero’s utility bills are now $1,300 a month.

Those who want to take on these stores can find it impossible to buy. If you’re poor — and many people in these towns are — and interested in a risky deal, few banks will give you a loan.

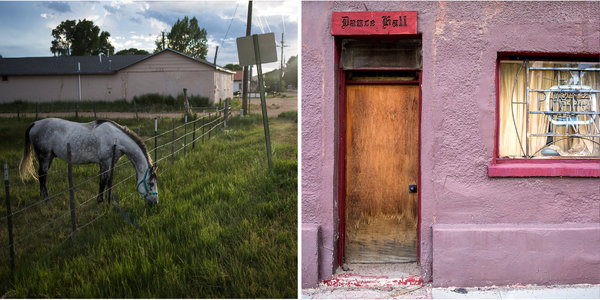

Left, a farm in San Luis. Right, a shuttered restaurant on Main Street.

Nick Cote for The New York Times

Mr. Trump’s proposal for 2018 includes a $4.7 billion cut in discretionary spending at the Department of Agriculture, including a 25 percent reduction in food stamps over a decade and the elimination of the Rural Business-Cooperative Service, a program that has extended credit to people who want to buy businesses like R&R Market.

The White House has said much of this assistance can come from the private market or other federal agencies.

And the administration’s new head for rural development, Anne Hazlett, said in an email that the Agriculture Department would prioritize small-town America, regardless of reductions. Mr. Trump’s budget, she noted, proposes a new program dedicated to rural distance learning, broadband and community facilities. This would cost $162 million.

Some see this as small comfort in the face of such drastic cuts. “Many in agriculture and rural America are likely to find little to celebrate within the budget request,” Representative Robert B. Aderholt, a Republican from Alabama, said in a recent congressional hearing.

In recent years, some communities have united to save their grocery. In Walsh, Colo.; Iola, Kan.; and Anita, Iowa, residents rescued their markets by forming cooperatives or public-private partnerships.

Out on Nebraska’s prairie, the high school students in Cody came together to open Circle C Market in 2013, selling goods out of a building made of straw bales.

Here in San Luis, the Romeros are trying to sell their market and six upstairs apartments for $600,000, half of what an appraiser gave as its value.

The Romeros want to retire, but they have not found a buyer for the market.

Nick Cote for The New York Times

They have solicited nieces, nephews and cousins to take over.

Some have shrugged it off. Too much commitment, too little return.

Two sons have their own lives and little time for the town market. One, Steven, runs the family ranch — his contribution to the community. “The store and the culture and the farming and the land go hand in hand,” he said.

Now, Mr. Romero is making peace with the fact that the shop could pass out of the family under his watch. If it stays open at all.

These days, when neighbors stop by, Mr. Romero leans in with a question.

“Want to buy a store?”