New York Times: When the Menu Says ‘Organic,’ but Not All the Food Is

Bareburger’s packaging advertises the food as organic — but for its beef burger, the restaurants use both 100-percent organic beef and a blend from Pat LaFrieda that’s only 75- to 80-percent organic. Credit: Nicole Craine for The New York Times

by Priya Krishna | Aug. 13, 2018

The term doesn’t mean much in restaurants, which are not required to undergo the same rigorous certifying process as farms and food companies.

About four years ago, Gil Rosenberg started eating at Bareburger, an international restaurant chain, after undergoing surgery that left him prone to infection and more inclined to eat organic meat. And the sign outside the Bareburger in Astoria, Queens, where he first ate prominently displayed the word “organic” above the restaurant’s logo.

Last fall, though, Mr. Rosenberg, 51, saw a Pat LaFrieda truck pull up outside a Bareburger in Forest Hills, Queens, to unload beef patties, and noticed that the packages lacked the “certified organic” seal authorized by the United States Department of Agriculture.

He wrote to Bareburger’s chief executive, Euripides Pelekanos, who eventually met with him and told him that 75 to 80 percent of the beef in the burgers was organic. This would count as “made with organic” but not “organic” under the federal regulations.

At this point, the typical customer would have just stopped eating at Bareburger. But Mr. Rosenberg was intent on making change: He went through the restaurant’s trash and found containers for mayonnaise and tomatoes, neither of which had the organic seal. He started distributing fliers outside some outlets that asked, “Is Bareburger REALLY organic?” He called Bareburger’s food suppliers to tell them that the restaurant was misrepresenting itself.

Still, the word “organic” continues to appear on many of Bareburger’s signs and on its packaging. “To me,” Mr. Rosenberg said, “it seems like an attempt to deceive and an attempt to defraud.”

But Bareburger is not necessarily breaking any rules. While farms and other businesses that want to advertise their wares as organic have to answer to certifying organizations that conduct annual inspections for the Department of Agriculture, restaurants do not. A restaurant can seek organic certification if it wants, but is not required to.

Under the department’s current rules, restaurants (characterized as “retail food establishments”) may call their food organic if they have made what Jennifer Tucker, the deputy administrator of the National Organic Program, called a “reasonable” effort to use organic ingredients.

There is no precise definition, however, of what constitutes a reasonable effort, and no monitoring body for enforcement. If the department receives a complaint that a restaurant is falsely billing its food as organic, Ms. Tucker said, it will investigate the claim and if necessary, send a letter asking the owner to stop using the term.

In 2002, the Department of Agriculture started the National Organic Program to create uniform standards, like not using synthetic fertilizers or genetic engineering, for farms and other businesses that produce, handle or process food. To enforce the rules, the agency works with organizations that assess and certify compliance.

Restaurants were exempted, Ms. Tucker said, because the biggest concerns at the time were farming practices and food production. The certification process is expensive, and it was thought that requiring compliance might impose too heavy a burden on restaurateurs.

Besides, “there weren’t a lot of restaurants making organic claims,” said Connie Karr, the certification director of the nonprofit organization Oregon Tilth, which certifies businesses as organic. “I assume that back then, it just wasn’t an issue.”

Since then, organic products have soared in popularity; they are in 82 percent of American homes, according to the Organic Trade Association. Organic food alone generates more than $45 billion a year in sales. And many restaurants have joined in, labeling their food organic without seeking certification.

At Bareburger, Mr. Pelekanos said he started using the term because he was trying to buy organic ingredients whenever possible and wanted to draw attention to that. Three and a half years ago, he said, he started buying 100 percent organic beef from Vermont Country Farms in addition to a 75-to-80-percent organic blend from Pat LaFrieda; the restaurants now use both, “based on market pricing, flavor, consistency and availability,” a Bareburger spokesman said. (Agriculture Department guidelines for farms and other businesses say a product must contain at least 95 percent organic ingredients — excluding salt and water — to be labeled organic.)

Mr. Pelekanos said he had never claimed that all of Bareburger’s menu items were 100 percent organic. And he has no plans to seek certification for any of the 41 Bareburger restaurants in the United States.

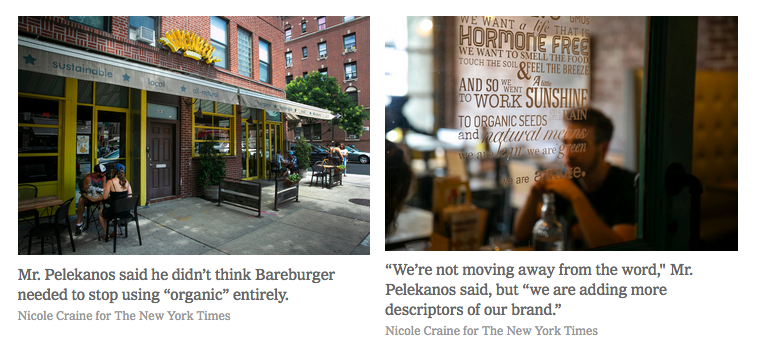

But at some newer Bareburger locations, words like “local” and “sustainable” — and in certain cases no words at all — have replaced the word “organic” near the logo.

“We’re not moving away from the word,” Mr. Pelekanos said, but “we are adding more descriptors of our brand.”

Mr. Pelekanos said he didn’t think Bareburger needed to stop using “organic” entirely. “Why are we going to run away from a word, when we have spent so much time and energy over the years to serve so much organic food in our restaurants, and we charge a premium for it?” he asked.

Vladimir Grinberg has intentionally chosen not to have his restaurant certified organic.Credit: Nicole Craine for The New York Times

Vladimir Grinberg has been an owner of the Organic Grill, in the East Village of Manhattan, since it opened in 2000, before the National Organic Program existed. “Nobody knew about organic then,” Mr. Grinberg said, so to call the restaurant “organic” has never been a marketing ploy.

He said all the food served at the restaurant is organic. But he has chosen not to have it certified as such. “It is our own transparency and integrity that makes us organic, and not someone that puts the label,” he said. “I don’t think the government knows more about food than we do.”

Ms. Tucker, of the National Organic Program, said a few restaurants around the country have chosen to undergo the rigorous process to be certified organic — though the department does not track them closely.

Erica Welton and Dennis Hoover, founders of the Organic Coup, a West Coast fast-food chain.Credit: Peter Prato for The New York Times

Dennis Hoover and Erica Welton worked as executives at Costco before opening their certified-organic fast-food restaurant chain, the Organic Coup, on the West Coast. At Costco, “we were doing a million dollars in conventional string cheese,” recalled Mr. Hoover, “and then we brought in organic string cheese, and we did a million five.”

“We saw the confidence that people had in the U.S.D.A. organic label” at Costco, Ms. Welton said. “We wanted to make sure people coming through the doors of our restaurant had the same confidence.”

Mr. Hoover said most of the Organic Coup’s 16 locations are now making a profit. “In retail, you have this transparency in that you are required by the U.S.D.A. to label all your products,” he said. “The restaurant industry is behind.”

But being a certified-organic restaurant comes with challenges on top of the already difficult task of running a dining business: meticulous record keeping, extensive staff training on organic rules, fees in the thousands of dollars and lengthy inspections that involve scrutiny of everything from produce invoices to cleaning materials.

Several certification organizations said that restaurants often approach them about becoming certified, but then are discouraged by the requirements.

Alberto Gonzalez, who ran one of New York’s first restaurants to be certified organic.Credit: Nicole Craine for The New York Times

“It is doable, but it is not easy,” said Alberto Gonzalez, an owner of one of New York City’s first certified organic restaurants, Gustorganics, which operated from 2008 to 2015. Each dish, for example, involved as many as 25 ingredients, and all of them had to be organic; but some ingredients had only one source — a farm or producer — that could supply an organic version.

“If there was a shortage, we were struggling,” he said. “You have nowhere to go.”

Ashleigh Knecht, a certification coordinator for the Northeast Organic Farming Association of New York, said the regulations seem tailored more for farms than for restaurants, so it could be difficult to figure out how to apply them to the restaurant setting.

For many diners, organic certification of restaurants doesn’t seem to matter much. Some even distrust the designation.

“What’s more important to me is the restaurant’s mind-set and attitude toward the food chain,” said Noah Youngs, who was having lunch recently at a Bareburger on the Lower East Side. “People earn the label ‘organic’ all the time and still have terrible practices.”

Timsie Malaney, a cardiologist at another table, said she preferred that restaurants list their meat and produce suppliers — as they do on the Bareburger menu — rather than point to their organic certification. “It’s just a label,” she said. “They are not telling you where the product is coming from.”

The Department of Agriculture doesn’t plan to change its rules to require restaurants to seek organic certification, an agency spokeswoman said. If customers are skeptical of a restaurant’s claim to be organic, they should submit a complaint through the department’s website, she said.

Mr. Rosenberg filed one last November about Bareburger, and didn’t get a response until May, simply confirming receipt of the complaint. He said he hasn’t heard anything further.

The Department of Agriculture spokeswoman would not comment on the individual complaint, but said, “We are making progress toward the goal of a customer friendly system that is faster and even more transparent. There are many factors that impact the time an investigation takes.”

Mr. Rosenberg’s expectations are low. “Do I expect the U.S.D.A. to do anything for me?” he asked. “No. Zero. I don’t think anyone cares.”