New York Times: The Real Villain Behind Our New Gilded Age

by Eric Posner and Glen Weyl | May 1, 2018

The comedian Chris Rock once said, “If poor people knew how rich rich people are, there would be riots in the streets.” Populist revolts throughout the world may not count as street riots, but they do reflect disenchantment with not just our government but also liberal democracy itself.

In the past two decades, growth rates in the United States have fallen to half of what they were in the middle of the 20th century. The share of income accruing to the top 1 percent has nearly doubled since the 1970s, while the share of income going to all workers has fallen by nearly 10 percent.

These are the marks of our new Gilded Age. It’s tempting to blame impersonal market forces such as globalization and automation for widening inequality. But the true villain would be familiar to anyone who lived through the previous one: market (that is, monopoly) power.

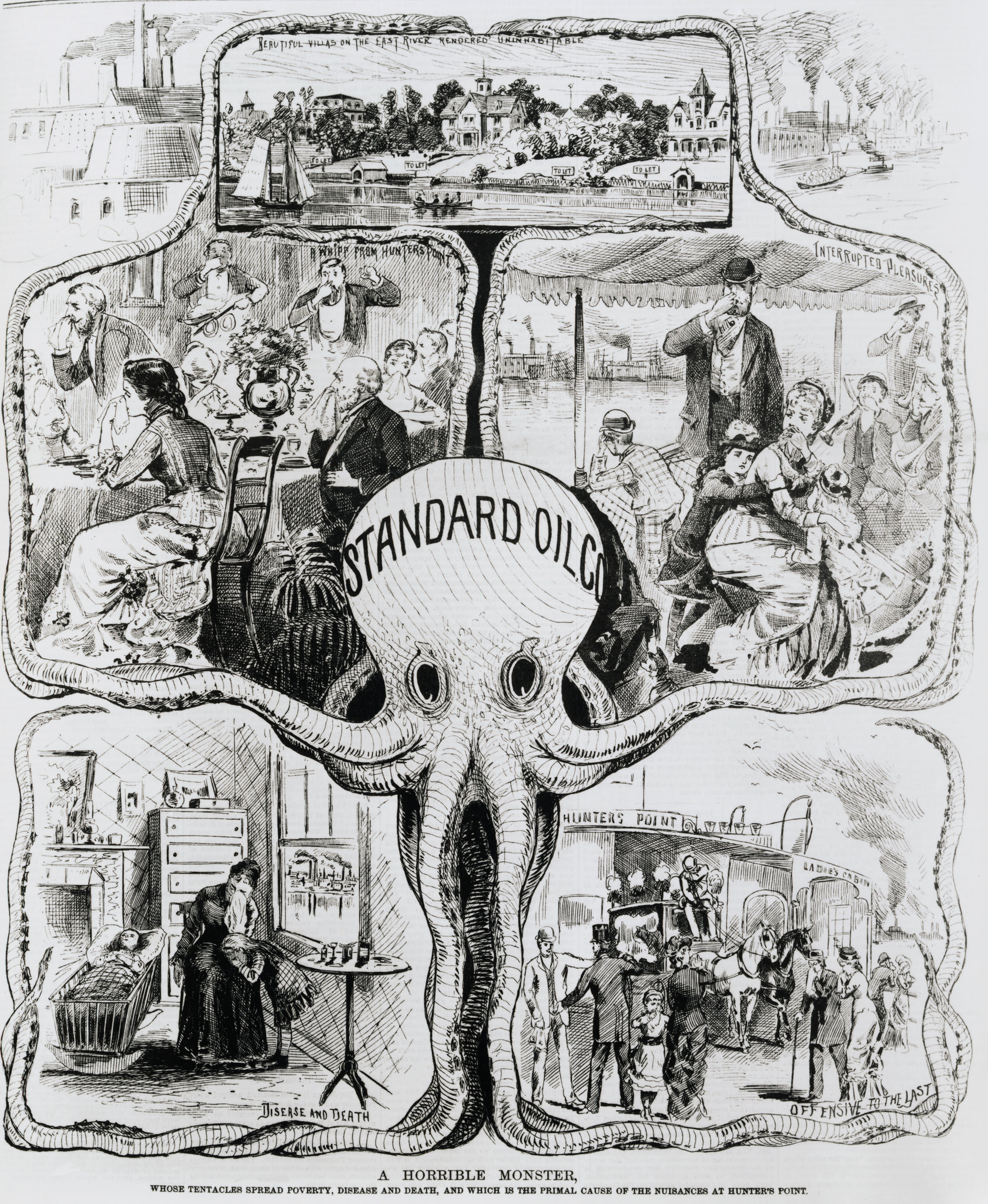

An 1880 political cartoon from a New York paper depicting Standard Oil — one of the great monopolies of the 19th century — as a “horrible monster, whose tentacles spread poverty, disease and death.”Credit Bettmann Archive, via Getty Images

The great monopolies of that period — Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, the sugar trust, the financial and railroad interests — used their power to corrupt the economy and politics. Market power both reduces growth and increases inequality. Recognizing this, leaders put into place antitrust and worker protection laws.

Today, market power takes new forms, but the solution is the same: antimonopoly laws and laws protecting workers, but updated for the problems of the 21st century.

The era of “supply-side economics” championed by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher — which called for tax cuts, deregulation and narrow antitrust enforcement — explains a lot of our current predicament. The key assumption of that era was that markets work best when the government focuses exclusively on enforcing contract and property rights.

This theory turned out to be wrong — not because it celebrates the market but because it misunderstands it. Two centuries earlier, Adam Smith pointed out that the easiest way for businesses to earn profits is not by slashing costs and innovating but by agreeing among themselves not to compete — to exert market power to raise prices or lower wages.

This sort of agreement is now illegal, but businesses have nevertheless found new and creative ways to achieve monopoly profits, while antitrust enforcers have fallen behind.

First, in the 1970s people began trusting their money with institutional investors, like BlackRock and Vanguard, which operate mutual funds that buy shares of all the major corporations. Because the institutional investors bought corporate shares incrementally over a long period of time, hardly anyone noticed when they obtained the biggest stakes of competing firms. For example, BlackRock and Vanguard are among the biggest owners of all the airlines, which means they benefit when the airlines raise prices. An important new series of economic studies suggest that as the institutional investors obtain greater market share, consumers pay higher prices and companies invest less.

Second, a growing body of research indicates that corporations have increased their profits by obtaining power over labor markets. Larger employers can underpay workers simply because workers can find few other employers that are willing to hire them. Faced with reduced wages, some workers quit or go on welfare, fueling the increasingly low labor force participation and rising deficits we see today. One example: Several years ago, many farm equipment manufacturers merged, creating a handful of giant companies like John Deere. This in turn led to a smaller number of farm equipment dealerships in many places. With fewer places to work, farm equipment mechanics had to either accept lower wages or find work in other fields.

Businesses have found other ways to extend their market power. The sandwich maker Jimmy John’s notoriously used covenants not to compete to block its workers from quitting to work for a competitor — which most likely held down wages. Antitrust authorities have focused on mergers and what they might mean for consumer prices but have ignored the possibility that they might push down the wages of workers.

A Jimmy Johns Gourmet Sandwiches franchise in Metairie Louisiana.CreditJulie Dermansky/Corbis, via Getty Images

Third, the rise of the internet has bestowed enormous market power on the tech titans — Google, Facebook — that rely on networks to connect users. Yet again, antitrust enforcers have not stopped these new robber barons from buying up their nascent competitors. Facebook swallowed Instagram and WhatsApp; Google swallowed DoubleClick and Waze. This has allowed these firms to achieve near-monopolies over new services based on user data, such as training machine learning and artificial intelligence systems. As a result, antitrust authorities allowed the creation of the world’s most powerful oligopoly and the rampant exploitation of user data.

According to one study, the power of firms to raise prices above the competitive level or cut wages below it increased more than threefold from 1980 to 2014.

To revive economic growth and restore equality, we need to update the solutions first developed a century ago. Then, the focus was on breaking up monopolies, prohibiting cartels and blocking mergers. These laws helped advance broadly shared prosperity, but owners of capital devised strategies to evade them. These strategies must be addressed with new regulatory approaches.

Institutional investors need to be blocked from further expansion and forced to restructure. They should be allowed to own shares of no more than one company per industry, or to own no more than a small portion of every company — say, 1 percent — if they want to remain fully diversified.

Antitrust authorities should target firms that use mergers to seize control of labor markets. Farm equipment dealers in a town should be allowed to merge only if mechanics and other employees will have a range of employment options after the merger. It is possible that some of the country’s biggest employers, like Amazon, the Compass Group food service company and Walmart, need to be broken up.

And regulators need to get more aggressive with tech monopolies and stop them from absorbing innovative rivals. Facebook’s market power is what makes scandals like Cambridge Analytica possible. Senator Lindsey Graham nailed it with a question that Mark Zuckerberg could not answer: “If I buy a Ford, and it doesn’t work well, and I don’t like it, I can buy a Chevy. If I’m upset with Facebook, what’s the equivalent product that I can go sign up for?”

We also need a renewed public awareness of the dangers of monopolies to ensure that in the future antitrust enforcers feel the pressure to keep up with the ever-changing faces of monopoly power.

While Democrats have recently tried to revive the spirit of the antimonopoly movements of the Gilded Age, this is an issue on which both parties might find common ground today — just as they did in the era of the trustbusting Republican President Teddy Roosevelt. No one should defend monopoly power.