New Food Economy: Whole Foods workers are moving to unionize. Read the letter sent to employees nationwide

by Sam Bloch & Joe Fassler | September 6th, 2018

“We cannot let Amazon remake the entire North American retail landscape without embracing the full value of its team members.”

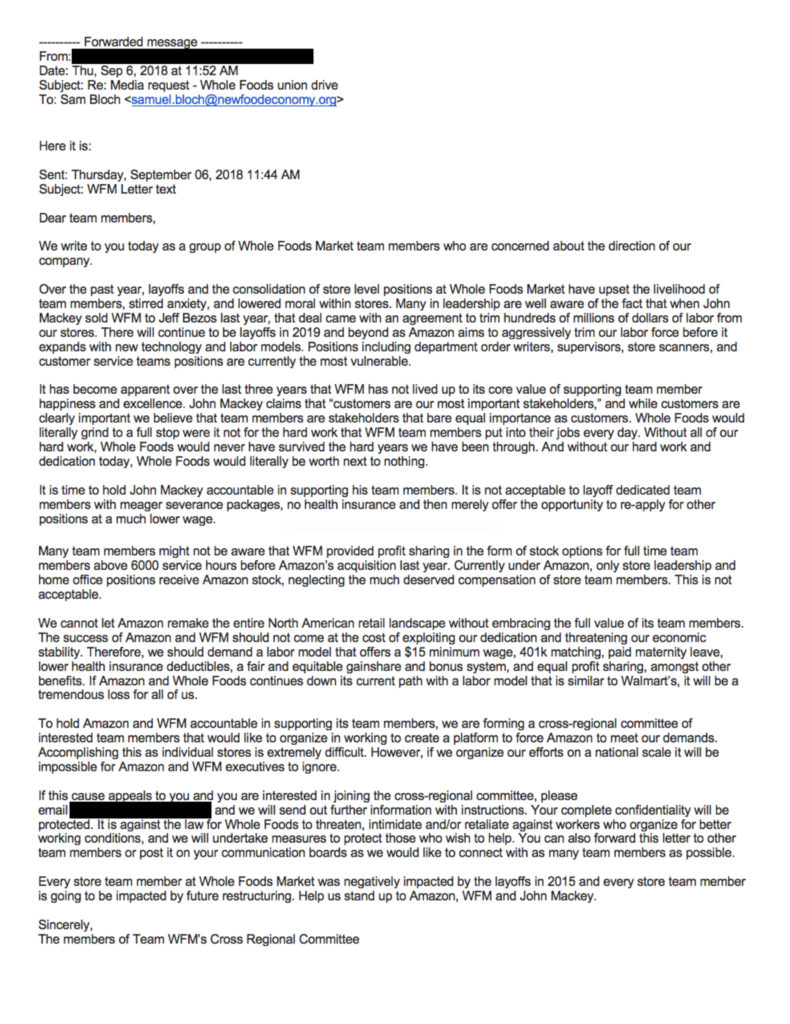

Updated September 6, 4:25 p.m., EST: A group of Whole Foods Market workers on Thursday sent an email to employees at most of the grocery chain’s 490 stores, urging the company’s workforce to unionize. The email—which follows in full below—depicted a company culture in disarray, with workers fearing imminent jobs cuts in the wake of Amazon’s acquisition.

“Over the past year, layoffs and the consolidation of store level positions at Whole Foods Market have upset the livelihood of team members, stirred anxiety,” and lowered morale within stores, the email said. It also alleged that Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods came with an agreement to trim hundreds of millions of dollars in labor costs from the chain’s stores.

“There will continue to be layoffs in 2019 and beyond as Amazon aims to aggressively trim our labor force before it expands with new technology and labor models,” the email went on. “Department order writers, supervisors, store scanners, and customer service teams positions are currently the most vulnerable.”

For Whole Foods workers the choice is clear: To protect their jobs against future cuts, they must unionize—not just at the store level, but chain-wide. The email was an attempt to find current employees willing to join a “cross-regional committee,” one that would help workers coordinate across 11 regional offices to “create a platform to force Amazon to meet our demands.” As outlined in the email, those demands included a $15 minimum wage, 401k matching, paid maternity leave, and lower health insurance deductibles, among other benefits.

The email also specifically mentioned stock options and profit sharing, which appear to be a bone of contention for workers. According to the email text, full-time Whole Foods workers were entitled to stock benefits once they’d worked 6,000 hours. After Amazon’s acquisition, the email alleged, stock benefits were limited only to those in store leadership and corporate positions. We were unable to independently verify those details, though Whole Foods’s 2016 annual report mentions the availability of stock options for both full- and part-time employees who have worked 6,000 hours. In a 2017 SEC filing, the company reported a net tax deficiency of $65 million “related to cancellation of team member stock options.” Amazon did not respond to our questions regarding stock options for employees by press time.

The workers’ effort is backed by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU), a New York-based division of the United Food and Commercial Workers union, which represents workers at grocery chains like Kroger and Albertsons. If the Whole Foods workers’ union materializes, it would be Amazon’s only known union in the United States—one representing just a portion of its 566,000-person global workforce.

Whole Foods workers have tried to unionize in the past with limited success. According to an RWDSU spokeswoman, a union campaign at a store in Madison, Wisconsin—which John Mackey, Whole Foods’s founder and CEO, called “a very sad chapter in the history” of the company—ended without a contract. Mackey, who once infamously compared labor unions to herpes, has since insisted that his employees simply have no need to unionize. “We’re not anti-union so much as beyond union,” he told a Yahoo Finance reporter in 2013.

Though it’s too soon to know where this nascent effort will end up, an email like the one distributed on Thursday was probably inevitable. Before Amazon’s acquisition, Whole Foods was well known for above-and-beyond worker treatment, with better-than-average pay and benefits packages rarely seen in the grocery industry. Though food retail jobs are among the nation’s lowest-paying, Whole Foods developed a reputation for being one of the few chains in the country where you could bag groceries and still earn a halfway decent living. Even after Whole Foods laid off 1,500 workers in 2015, or 1.6 percent of its workforce, its benevolent reputation survived intact. In 2017, Whole Foods made Fortune’s “Best Employers to Work For” list for the 20th consecutive year.

Amazon doesn’t have the same reputation. Yes, the corporate employees at its Seattle headquarters receive the same over-the-top perks and benefits typically offered by leading tech companies, driving up the cost of living in the Emerald City. But Amazon has been notoriously tight-fisted with workers in its sprawling fulfillment centers. In April, a New Food Economy investigation found that a high proportion of Amazon workers rely on federal food assistance to make ends meet—prompting Vermont’s Independent Senator Bernie Sanders to sponsor legislation, the so-called BEZOS Act, that would tax employers whose employees over-rely on programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps).

Beyond that, there are signs that Amazon envisions a retail landscape that circumvents human workers altogether. The company is already piloting cashierless stores in cities across the country, where shoppers pay by smartphone without ever visiting a register (or interacting with a human employee). This push toward automation represents a direct threat to frontline Whole Foods workers, and seems to be one example of the “new technology” Thursday’s letter cited as an imminent concern.

How will the company integrate Amazon’s automated, tech-first approach with Whole Foods’s employee-friendly brand? It won’t be easy—and, if Thursday’s email is any indication, the culture clash is only likely to intensify.