Most accounts treat black migration out of the South after the New Deal as a voluntary and profitable move. “Millions of poor farmers,” writes Robert Paarlberg, a public policy professor at Wellesley College, in Food Politics, “left the land [to take] higher paying jobs in urban industry.” Michigan State legal scholar Jim Chen called this migration a “liberating moment” that allowed rural black Southerners to escape to the urban north, away from “the dreariness of their former lives on the farm.” He concluded, “[t]he jobs were there, the wages were better, and black America was ready to move.”

In reality, historians have established that white Southern leaders encouraged mechanization and co-opted policy in order to pressure blacks to leave. With the backing of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), large farmers cut costs and drove small farmers out of business, while local USDA agents discriminated against black farmers on a systematic basis: by 1920, there were 925,000 black farmers, and by 1970, 90 percent of them were gone. Some of these farmers left for better opportunities, but more were forced out in what the historian Donald Grubbs calls one of the “largest government-impelled population movements in all our history.” When they reached the cities, they entered a white-dominated society where they were treated as inferiors, and “an economy that had relatively little use for them,” as Gavin Wright, an economic historian, puts it, with black unemployment rates between 10 and 15 percent “as early as 1950” and “up to 30 percent” in several major cities, a decade later, writes Michael Munk, a historian.

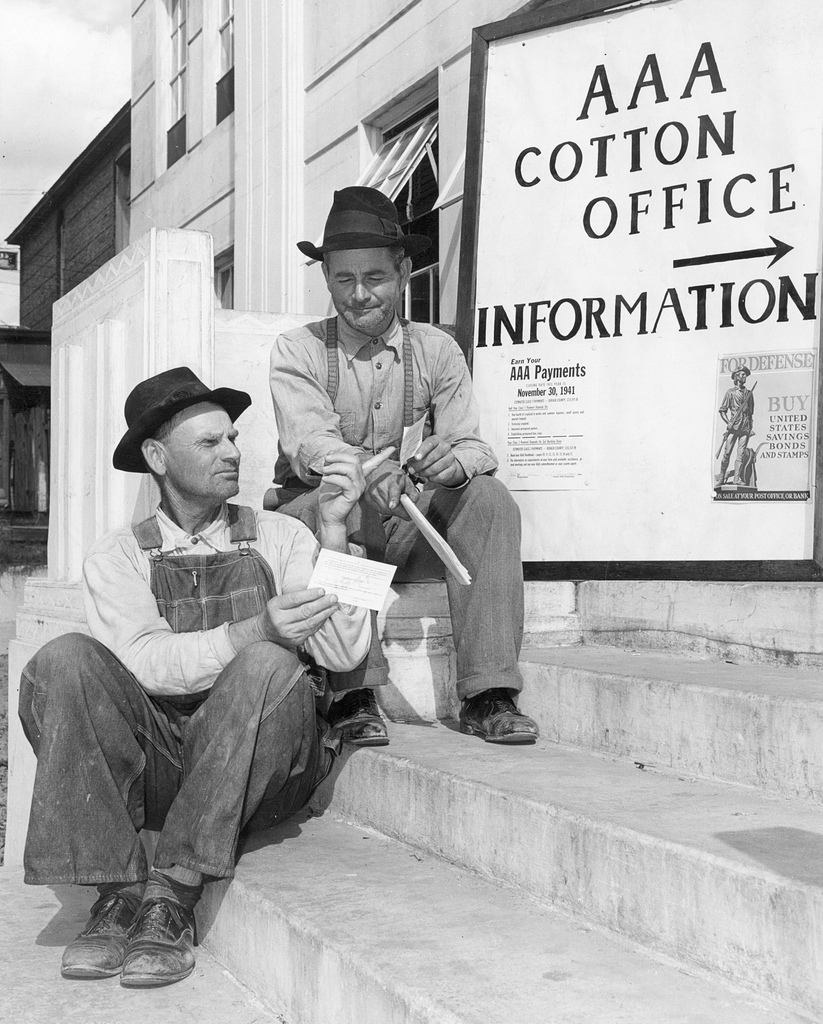

Flickr / USDA

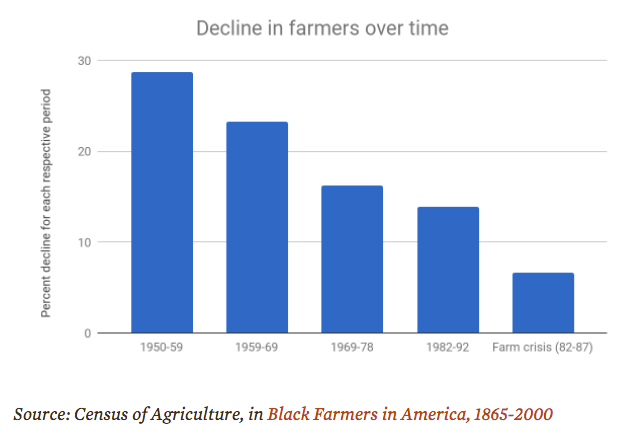

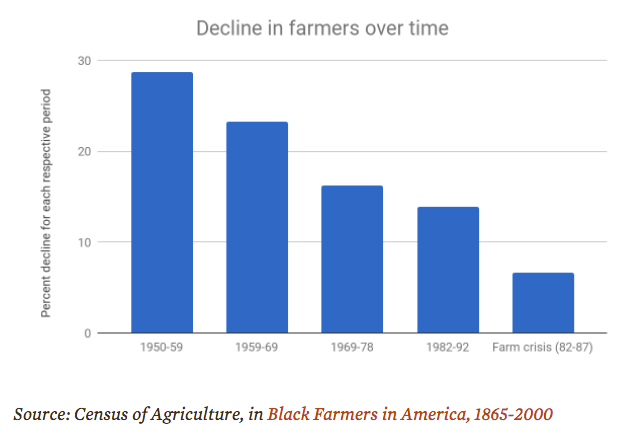

From 1959 to 1969, the number of black farmers declined by over two-thirds, almost triple the rate of white farmers

As the civil rights movement gathered steam, assaults on black farmers intensified. By the 1950s, writes Gilbert Fite, an agricultural historian, “any program for small, poverty-ridden farmers in the South became entangled with the civil rights movement.” The founder of the Citizens’ Council, reported Bayard Rustin, the civil rights leader, drew up a plan to remove 200,000 African-Americans from Mississippi by 1966 through “the tractor, the mechanical cotton picker … and the decline of the small independent farmers.” As government-funded mechanization continued apace, “tens of thousands” of poor farmers were forced out of agriculture: they eked out an existence in the hinterlands, in shacks, without “food or adequate medical care.”

“There were over nine times as many black farmers in 1920 as there were minority farmers, total, in the 2012 census.”

Black farmers who held onto their land used their independence to support civil rights workers, which often made them targets for lynch mobs and local elites. When Bob Moses, a key figure in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), first arrived in Mississippi, he stayed with E.W. Steptoe, a landowner in Amite County, who was the local NAACP chapter president. Akinyele Umoja, professor of African-American studies at Georgia State University, writes that “many SNCC workers depended on the protection of and were inspired by Black farmers like Steptoe.” Another landowner and NAACP member, Herbert Lee, sometimes drove Moses around Amite County. E.H. Hurst, a member of the state legislature, later murdered Lee for his work with Moses.

As Pete Daniel documents in Dispossession, USDA agents withheld loans black farmers needed to operate, denied crop allotments, withheld research and expertise, and overlooked fraud and abuse in elections for powerful local committees that distributed resources to local farmers. From 1959 to 1969, black farmers declined by over two thirds, almost triple the rate of white farmers. The story of black farmers is so thoroughly omitted from the folk history that, in 2014, a writer for Modern Farmer claimed “there are more minority farmers than ever before,” when in reality, there were over nine times as many black farmers in 1920 as there were minority farmers, total, in the 2012 census.

Myth: Earl Butz was a pivotal figure

“Butz inaugurated almost none of the programs his critics say he did.”

That Earl Butz, secretary of agriculture under Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, was fired for a racist joke may help explain why journalist Michael Pollan has described him as the architect behind America’s industrialized food system: he makes an easy villain. Many writers lead their accounts with remarks on Butz’s character, repeat his admonitions that farmers “plant fence row to fence row” and “get big or get out,” then summarize how he dismantled New Deal supply management systems and encouraged maximum production; introduced direct payments to farmers in lieu of favorable loans; and displaced small farmers. One group of writers argues that Nixon’s USDA, under Butz, was responsible for “the last fundamental shift in agricultural policies.” Butz “[helped] shift the food chain onto a foundation of cheap corn,” writes Pollan. Nestle claims that he “encouraged farmers to produce as much food as possible.” Butz “forever transformed … the rural landscape once healthfully dotted by profitable small farms,” contends Bill Eubanks.

Butz inaugurated almost none of the programs his critics say he did: they began under earlier USDA chiefs, who had sided with big farmers since the New Deal. Ezra Taft Benson, secretary under President Eisenhower, not Butz, ended production controls for corn in 1959, and was the first to urge farmers to “get big or get out.” Kennedy severely weakened supply management with a farm bill that made programs voluntary for every commodity except wheat. Johnson bragged that his bill would drop prices “to the lowest possible cost” and that he would deal with “farm surplus and supply management” through increased exports, which he expected to grow by “50 percent” in a decade. Johnson’s law also introduced direct payments to farmers, which lasted through the 1980s.

Flickr / USDA

Fencerow-to-fencerow agriculture had been dominant in the Midwest long before Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz (center), entered office

Butz’s farm bill was “the logical extension of the acts of 1965 and 1970,” according to former USDA chief economist and Kennedy adviser Willard Cochrane. When that bill passed, monoculture had already taken hold. A series of contemporaneous studies, on the presence of wildlife habitats on farm properties, found that fencerow-to-fencerow agriculture had been dominant in the Midwest long before Butz entered office. “The big fallout of the ‘get big or get out’ mindset,” writes the environmental and agricultural historian James Sherow, “occurred during the Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson Administrations.” As Wendell Berry, who inspired Pollan’s food journalism, writes, “Butz’s tenure in the Department of Agriculture, and even his influence, are matters far more transient than the power and values of those whose interests he represented.”

Myth: The farm crisis began in the 1980s

“Numerous families lost their farms prior to the 1980s, often at higher rates.”

Journalists treat the 1980s farm crisis as if it were the “deepest rural crisis since the Great Depression.” Hollywood saw it that way: studios released two films about the crisis in 1984. A group of musicians held the first Farm Aid concert the next year. The public believed then, as journalists report now, that, prior to the 1980s, even farmers “on small parcels of land … could make a reasonably good living.”

What makes this story so strange is that the decline was significantly slower during the farm crisis, which lasted from 1982 to 1987, than in previous periods. There was a difference, however: a wealthier class of farmers was affected. A group of sociologists who interviewed a representative sample of Iowa farm operators during the crisis found that “persons most at risk of forced displacement from farming are found to be younger, better educated, and large-scale operators.” Wealthier farmers had been much more likely to take out large loans to expand their operations in the 1970s. As a result, when the Federal Reserve suddenly began to curtail inflation in 1979, raising the federal funds rate to a high of 21.5 percent in 1982, these farmers were hit hard by astronomical interest rates.

The farm crisis itself was real: families were forcibly and tragically displaced from their farms during the 1980s; the mythmaking begins when writers portray it as a starting point. Numerous families lost their farms prior to the 1980s, often at higher rates, yet their displacement was not perceived as a catastrophe, since they came from marginalized populations, such as rural blacks, Native Americans, and poor whites. By treating the farm crisis as an aberration, these writers conceal this larger tragedy and the decades of policy-making that caused it.

Myth: Land consolidation was inevitable

Between 1930 and 1992, the number of white farmers fell by 65 percent and black farmers by 98 percent, as farms became larger, almost all of them owned by white men. Willard Cochrane ascribed these changes to a “technological revolution.” Jim Chen writes that “technology inexorably increases farm size.” Laurie Ristino and Gabriela Steier, both legal scholars, attribute consolidation to “efficiencies of economies of scale,” the “adoption of tractors . . . and combines,” and “the Green Revolution.” These writers share a sometimes unstated belief in autonomous technological “forces,” part of a discourse of technological determinism rooted in conservative ideology.

“Government policy that favored large-scale farmers forced modest growers out of business.”

But economists have reached a consensus that neither economies of scale nor technology give large-scale farms an edge over smaller ones. In 2013, USDA researchers surveyed the literature and concluded that “most economists are skeptical that scale economies usefully explain increased farm sizes.” Similarly, technology itself does not inherently—or as the USDA researchers put it, “explicitly”—benefit owners of large-scale farms. What technology does is allow farmers to substitute capital for labor, enabling those with sufficient capital to reduce labor costs. As a result, labor-saving technology can lead to land consolidation when combined with policies that provide commercial farms with easy access to capital, while withholding it from smaller ones, as happened in the United States.

Flickr / USDA

“Science does not apply itself, and technology does not introduce itself.”

Since before the New Deal, agricultural planners had advocated for consolidating farmland and mechanizing agriculture. An advisor under Eisenhower, John Davis, coined the term “agribusiness” to describe the vertically integrated, corporate structures that policymakers hoped would come to dominate the production, distribution, and marketing of farm products. While agribusiness proponents believed technology would force small farmers out of business on its own, they advanced policies that favored large-scale producers anyway. As the Monthly Review observed in 1956 when it wrote about concentration in agriculture, “Science does not apply itself, and technology does not introduce itself.” Then, as now, government policy that favored large-scale farmers forced modest growers out of business.

Policy makes politics

While conservatives have consistently pushed more aggressive, pro-agribusiness policies, liberals have often responded with pro-agribusiness policies of their own, even when that meant undermining their own natural allies: small and mid-sized farmers, farm workers, rural minority populations, and the small, independent businesses they support. The Democrats’ approach to agricultural policy has been so perplexing that academics have developed a rich literature, in the field of policy feedback, to understand it. Policy feedback is the study of the ways, as Theda Skocpol recently described it, “in which policy fights and outcomes at one point in time set up, or closeoff, future possibilities.”

“If Democrats want to win more rural voters, they must develop an alternative and progressive rural policy.”

Researchers in policy studies have paid special attention to the Democrats’ relationship with the American Farm Bureau Federation, a conservative interest group that rose to power with federal help. Even “scholars not inclined to emphasize the independent role of government activity,” writes Paul Pierson, a political scientist, have linked “the Farm Bureau’s development … to policy feedback.” The Farm Bureau “grew out of the movement for improved farming methods,” pushed by businessmen, scientists, and, “especially,” USDA. The group “eagerly recruited commercial farmers” and was “not at all inclined to expand beyond that constituency.” From the beginning it styled itself as a bulwark against government intervention and leftist populism: James Howard, the first president of the Farm Bureau, claimed that he stood “as a rock against radicalism.”

As New Deal negotiations began, the Farm Bureau pursued the interests of white, Southern planters, and liberals made significant concessions to them, out of expediency. One of the most significant was “predominant influence” over the administration of the AAA, which the Farm Bureau used to favor large producers and consolidate its power. The group’s membership increased six-fold between 1933 and 1945, as it lobbied for large growers at the expense of smaller farmers. As Mancur Olson concluded in his widely cited study of interest groups, “the Farm Bureau was created by the government.”

From that point on, the Farm Bureau played an expanding role in farm policy, using its increasing power to not only push out small farmers but to oppose progressive legislation at every opportunity. The Farm Bureau, among other things, helped pass the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, sought to repeal the federal income tax in the 1950s, bitterly fought Medicare in the 1960s, opposed the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1980s, lobbied against health care reform in the 1990s, and boasted of killing the Waxman-Markey climate bill during President Obama’s first term.

Flickr / USDA

Tom Vilsack, secretary of agriculture under President Obama, is a member of the Farm Bureau and repeatedly spoke at its annual conference during his term

Today, the Farm Bureau and its state branches continue to oppose a wide swathe of progressive legislation. The Farm Bureau’s 2016 list of policy resolutions ran longer than 200 pages and expressed, among other conservative positions, the organization’s opposition to Medicare expansion, universal health care, government-funded high-speed rail, “efforts to remove references to Christmas,” gay marriage, and “special privileges to those that participate in alternative lifestyles.” The Missouri Farm Bureau declared, in 2017, its opposition to the use of “religious legal code,” a euphemistic phrase for Sharia law, in American courts; more stringent gun controls; and a federal minimum wage, all while supporting “right-to-work” legislation, harsher penalties for drug infractions, and a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced federal budget.

“Rather than funneling cash to large-scale farmers, Democrats should support workers and small-scale businesses.”

Nonetheless, Tom Vilsack, secretary of agriculture under President Obama, is a member of the Farm Bureau and repeatedly spoke at its annual conference during his term. His commitment went beyond words: Vilsack pushed the rapid growth of the federal crop insurance program, which sends millions of dollars to the Farm Bureau each year, while hurting smaller farms and the environment. In his own words, Vilsack prioritized crop insurance above all else, telling Farm Bureau members, at their 2013 annual meeting, that the farm bill “must start with the commitment … [to] a strong and viable crop insurance program.” Researchers at the University of Missouri found that the 2014 Farm Bill’s new crop insurance programs will increase crop insurance payments by 27 percent over a decade. As he left office in 2017, Vilsack urged farm groups to “be more vocal advocates of federal crop insurance subsidies.”

Vilsack is one in a line of Democratic politicians who have supported conservative policies that undermine their own party. If Democrats want to win more rural voters, they must develop and articulate an alternative, and progressive, rural policy. There are signs that this may be starting to happen. Family Farm Action, an advocacy group of progressive family-farmers, is attempting to rally small farmers and rural communities against the behemoth firms that dominate the American countryside. But since most people in rural areas are not farmers or farm workers, Democrats will need to expand their reach. Rather than funneling cash to large-scale farmers and corporations, Democrats should support workers and small-scale businesses. Rather than displacing poor and marginalized rural people, the party must empower them. As history has shown, to do otherwise would be not only disastrous for the party, but for the nation as a whole.